Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry continues showing how paternity cases affected life in the 17th century Massachusetts Bay Colony, concluding her description of the case of the Endicott family. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

Today I continue with the drama of the Zerubbabel Endicott paternity case of Salem, Massachusetts, found in the “Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Volume 1,” online at the University of Virginia.

To recap, Zerubbabel – the 18-year-old son of Governor John Endicott – was named in June 1654 by Elizabeth Dew, a maid servant in the Endicott household, as the father of her illegitimate child. The community’s response? Dew was sentenced to be whipped 12 stripes by the constable for her “pernicious lie” against Zerubbabel. The Endicott’s quickly discharged Dew and arranged for her to marry another servant in the house, Cornelius Hulett, on 30 June 1654.

The records also state that Cornelius Hulett was sentenced to be whipped 10 stripes for fornication with Dew before their marriage, “having confessed before Reverend Edward Norris and others.”

That same year, Zerubbabel married Mary, daughter of Samuel Smith. (They had several children before she died, then he married 2nd Elizabeth (Winthrop) Newman, daughter of Governor John Winthrop and widow of Antipas Newman.)

Despite the hastily-arranged marriage to Hulett, Dew did not withdraw her claims against Zerubbabel, the real daddy. She endured more lashes and public humiliation: in December, the court magistrates enforced a more serious punishment to silence her:

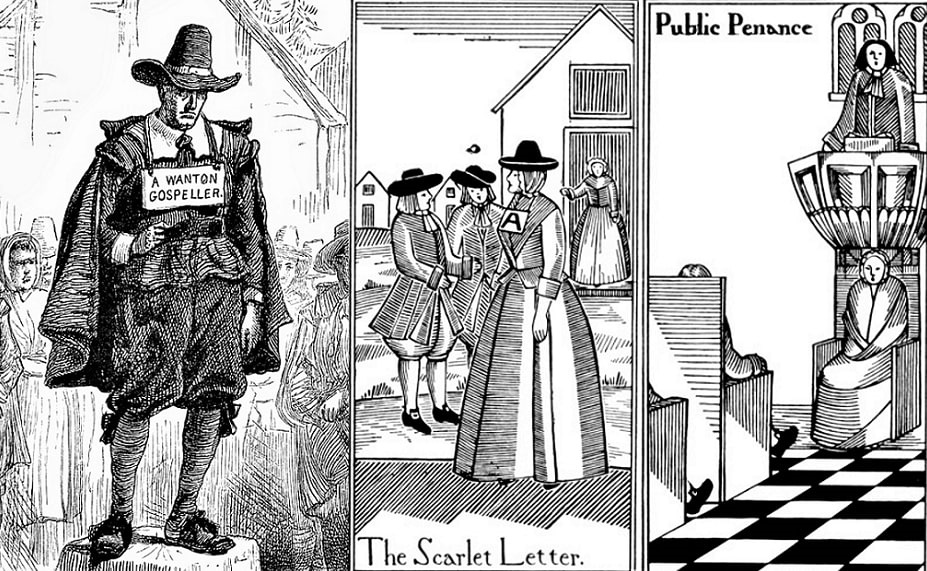

“Elizabeth Dew, alias Hulett, wife of Cornelius Hulett, for slanderous speeches against Mr. Zerubbabel Endicott in fathering her child upon him, to be whipped twenty stripes on some lecture day (weather to be more seasonable), a paper to be pinned upon her forehead with this inscription in capital letters: A SLANDERER AGAINST MR. ZERUBBABEL ENDICOTT.”

The court testimonies tell a different story.

Dulzebella Bishop (wife of Richard Bishop), and daughter Mary Bishop, gave depositions. They were established members of Salem, and lived near the North River just beyond Beckford Street. Richard Bishop served as a constable and jurist.

The Bishops deposed that Elizabeth Dew, Mrs. Endicott’s maid, came several times to their house on her mistress’s business and complained of Zerubbabel’s “unseemly words and actions.” For example, when she was at the work of lacemaking, he pulled her cushion from her and threw her down on the floor.

Dew also told deponents about going with Benjamin Scarlett (apprentice and servant to Governor John Endicott) and Zerubbabel to the farm via boat, and after going ashore, about two or three poles from the water, Zerubbabel followed her – and his carriage was such that she told him “I will not be your common baud.”

The deponents testified that they asked Dew about Cornelius Hulett, and how he carried himself to her. Dew told them: “He had never offered me wrong, and not so much as kiss me in all the time he had been in the house.”

Then deponents asked Dew why she did not complain to her master. Dew said: “I told Mary Gowen, and she replied, ‘I know thy condition alas poor wench,’” further stating that Zerubbabel had “insulted” her also.

The deponents also noted there were other young maids who had confided to them about Zerubbabel’s transgressions against them.

In Founding Mothers & Fathers: Gendered Power and the Forming of American Society, Mary Beth Norton believed that the Essex County justices were too quick in determining that Dew’s story was a lie, despite confirmation of Zerubbabel’s past prowling tendencies.

Dew told her story when asked to identify the man who impregnated her, but neither she nor anyone she confided in brought it to light before the time of her court date. Even though the Bishop women were credible witnesses, their testimony was not accepted as truth. Zerubbabel Endicott’s denial was believed, and Dew’s accusation was rejected.

And as far as the Endicott family tree – the apple (or is that pear?) does not fall far.

Zerubbabel’s son Zerubbabel Jr. is cited in Melinde Lutz Sanborn’s book Lost Babes: Fornication Abstracts from Court Records, Essex County, Massachusetts, 1692-1745. In the Court of General Sessions record from 18 January 1692: Zerubbabel Endicott Jr. (husband of Grace Symonds) was presented for adultery with Rebecca (Blake) Eames (wife of Robert Eames). Bound for 200 pounds. Rebecca was accused of witchcraft during the 1692 Salem Witch Trial hysteria, but did not go to the gallows.

While the famous Endicott pear tree (planted c. 1640 and still alive today!) continues to bear fruit, apparently Dew’s illegitimate child did not… another lost babe of Essex County, and a broken branch in the Endicott line.

Note: the photo of the Endicott pear tree shown above was taken in 1965 in Danvers (Old Salem Village), Massachusetts. It shows Anne and Ruthie Stearns (daughters of Rev. Howard Stearns, who was noted for his work on the 1692 witch hysteria, and assisted James Cooper and Ken Minkema in the transcription of Rev. Samuel Parris’ Sermon Notebook project). Read more at Witch Lore in Old Salem Village: Ruthie Stearns’ Family Connections.

Related Articles:

- Puritan Court Drama_Woman Won’t Identify Child’s Father

- Puritan Court Drama_Woman Won’t Identify Child’s Father, Part II

- Paternity Court Drama in 17th Century America

- Paternity Court Drama in 17th Century America, Part II

- Paternity Court Drama in 17th Century America, Part III

- Colonial Massachusetts Paternity Cases: The Endicott Story