Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry continues showing how paternity cases affected life in the 17th century Massachusetts Bay Colony – and, in particular, describes the case of the Endicott family. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

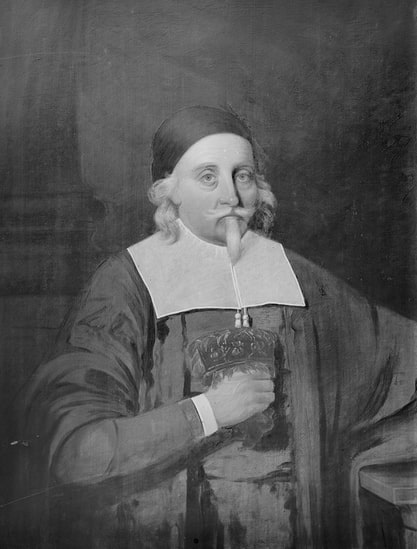

The highly-regarded Governor John Endicott (also spelled Endecott – the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony), the “Puritan par excellence,” is one of the most celebrated first settlers of Salem, Massachusetts.

The Emporia Gazette spotlighted Endicott as a “fine pioneer nurseryman” who planted a grove of fruit seedlings on his 1632 fertile land grant “Orchard Farm.” The famous Endicott pear tree is “unrivaled in all the land” for its antiquarian interest – it is North America’s oldest cultivated fruit tree – and is a living link in Danvers, Massachusetts, which connects “earliest New World life with today.” (Yes, the nearly 400-year-old pear tree is still alive, and continues producing fruit to this day!)

Governor Endicott’s son Zerubbabel has his own tale of prolificacy found in the “Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Volume 1” online at the University of Virginia. He planted his seed in the belly of a young maid, and this paternity drama features a badge of shame like the one Hester was forced to wear in Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter.

In June 1654 Elizabeth Dew, a servant to the Right Worshipful John Endicott of Salem, was sentenced to be whipped 12 stripes by the constable for a “pernicious lie” against Zerubbabel Endicott, the 18-year-old son of John Endicott. According to the court, Dew had committed slander when she named Zerubbabel as the father of her illegitimate child.

The court noted that Dew had also named (under what pressure, we’ll never know) Cornelius Hulett, a male servant also working in the Endicott home. Hulett was found guilty of fornication with Dew and sentenced to be whipped 10 stripes. Sources suspect that the Endicott family maneuvered a solution to absolve Zerubbabel by releasing Dew from her indenture and arranging a marriage to Hulett.

Apparently, the Endicott’s could not give Dew the boot fast enough. Dew and Hulett tied the knot on 30 June 1654, as noted in Salem records. I have not found the birth record of the babe in question.

Despite the hastily-arranged marriage to Hulett, Dew did not hush up and insisted Zerubbabel was the true daddy. In December, the court magistrates enforced a more serious punishment to silence her:

“Elizabeth Dew, alias Hulett, wife of Cornelius Hulett, for slanderous speeches against Mr. Zerubbabel Endicott in fathering her child upon him, to be whipped twenty stripes on some lecture day (weather to be more seasonable), a paper to be pinned upon her forehead with this inscription in capital letters: A SLANDERER AGAINST MR. ZERUBBABEL ENDICOTT.”

In Daughters of Eve: Pregnant Brides and Unwed Mothers in Seventeenth Century Essex County, Massachusetts, author Elise L. Hembleton asserts that the penalty enforced on Dew was of “unprecedented severity.” (P. 14) Hembleton also believes Dew fits the profile of the unwed mother prosecuted for the crime of fornication in Essex County prior to 1665.

Dew’s social station and lack of resources contributed to her predicament. Her situation was like the plight of Susannah Colburn of Dracut, who named the father of her illegitimate child as the son of her master and her midwife. Both women had no relatives to aid them. Also, both were servants in prominent households that wielded power within the community and the courts.

Dew was not the only lass in town to endure Zerubbabel’s advances, but she was the only one to go public. Once the word was out and the courts deposed witnesses, it was clear that Zerubbabel had a thing for young maids. Stay tuned for the skinny.

Note: Just as an online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, helped tell the stories of the Endicott family, they can tell you stories about your ancestors that can’t be found anywhere else. Come look today and see what you can discover!

Related Articles:

That picture of Endicott is puzzling. Surely that’s not his tongue? What is that? Such a strange picture. Say more please.

Hi Ellen,

Thanks for stopping by. The image you think is Endicott’s tongue is his beard — or goatee style.

My ancestor, Thomas Rood (Rude), was the first person in the American colonies to be convicted of incest, and became the only person executed for incest in America, in 1672.

Hi Julie, thanks for sharing. I know about that case and I know there was a child born from it. I will have to do a story on that.