Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry writes about court cases that may have influenced Nathaniel Hawthorne when he wrote “The Scarlet Letter.” Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

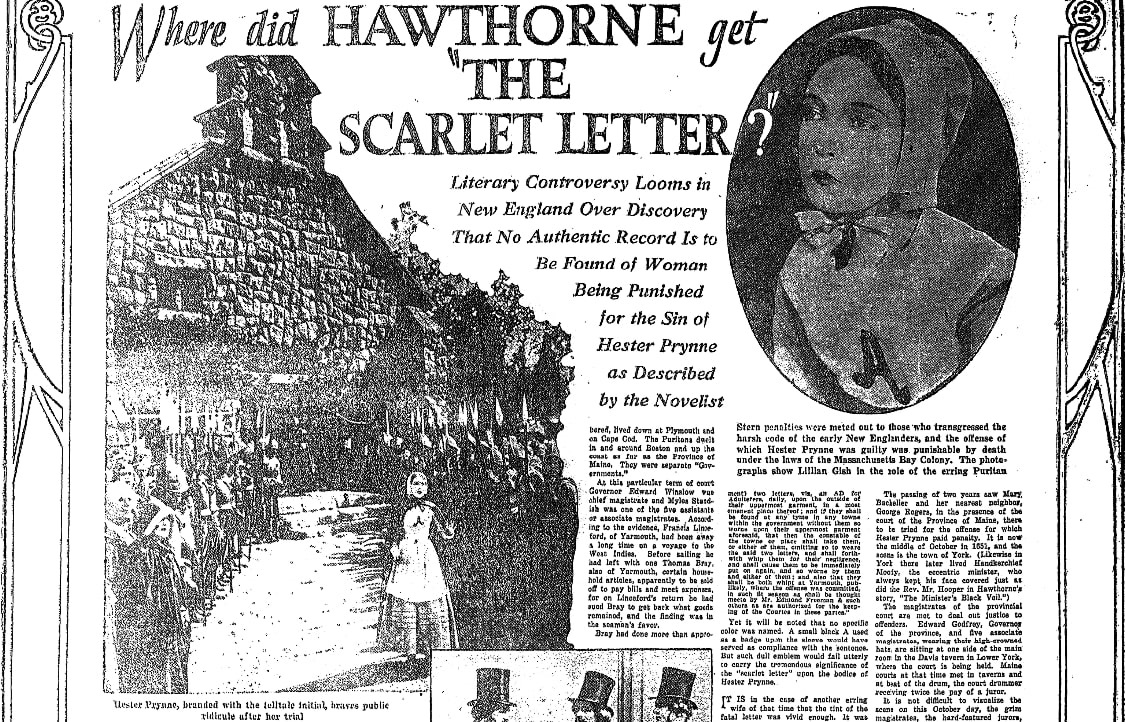

Author’s Note: In my last two articles, I covered a 1680 court case from Salem, Massachusetts, which may have been a hot source for Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The Scarlet Letter (see links at the end of this article). Today I look at a newspaper article published by Edgar Yates in 1927 on the literary controversy surrounding authentic sources for the story of Hester Prynne, the protagonist of The Scarlet Letter.

In the novel, Hester is charged with committing adultery in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and is sentenced to a punishment known as branding: she must forever wear a scarlet “A” embroidered on her dress to publicly shame her as an adulteress. However, in actuality the Colony’s penalty under the law for this crime was death.

Although Hawthorne’s son Julian, his son-in-law George Parsons Lathrop, and his biographer Lloyd Morris in The Rebellious Puritan, all claimed the source for Hester’s story was authentic, literary critics asserted no woman was ever sentenced in the Massachusetts Bay Colony for any offense whatsoever to wear a red cloth initial.

The argument was held that laws were strictly enforced, and Hawthorne’s novel was just a work of fiction. However, Yates proposed a few cases from the court archives as source material for The Scarlet Letter.

He noted there was much speculation on whether Hawthorne knew about these cases – but since his article was published, dozens of articles have provided evidence that Hawthorne did indeed have access to the court records Yates cited.

In addition to knowledge of the court cases, Hawthorne was aware of his ancestors’ roles with crime and punishment: they ordered Quakers to be whipped and “witches” to be hanged. All of this real-life background probably stirred Hawthorne’s imagination when he thought up the plot for The Scarlet Letter.

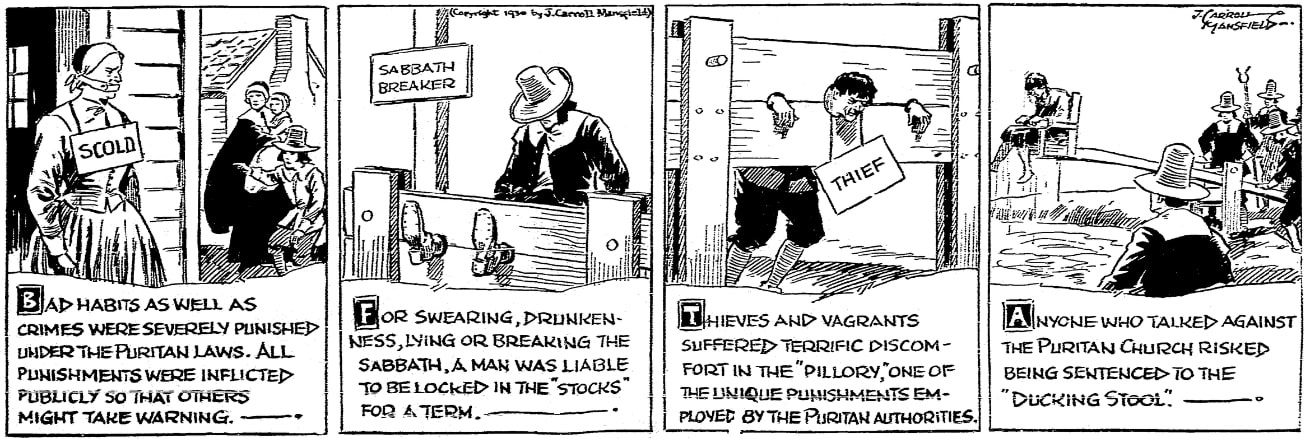

The Puritans had an array of punishments for various forms of wickedness.

Here are some of the court cases Yates cited in his article on Hawthorne:

In 1644 Mary Latham and James Brittaine [Britton] committed adultery and were sentenced to death. The case is mentioned in Governor Winthrop’s journal: “They died penitently.”

Next, Yates cited a case where branding was employed by the Puritan court. The brand, or letter initial, represented the crime of the transgressor and served as a constant badge of shame and humiliation.

Robert Coles was charged with drunkenness, a very serious crime for the pious Puritans – who were known to audit tavern goers.

In Coles’ case, the court decided that he:

“Shall wear about his neck to hang upon his outward garment, a D made of red cloth & set upon white, to continue this for a year & not to have it off at any time when he comes amongst company.”

Other examples of branding mentioned in the court cases include one defendant having to wear a “V” (for lewdness) and another a “T” (for thievery).

Although Plymouth Colony was a separate government apart from Hawthorne’s Salem, there was a case in Plymouth of adultery resulting in “A” branding.

Governor Edward Winslow and Myles Standish were among the authorities who oversaw the case that issued an “A” branding on 7 December 1641.

Francis Linceford traveled to the West Indies and left his possessions in the care of his friend Thomas Bray. When Linceford returned, he filed a lawsuit which claimed Bray abused the arrangement – but this seaman had more to worry about than his missing property.

Bray not only took liberties with Linceford’s possessions but helped himself to Anne, Linceford’s wife, who was more than willing to surrender her goods.

Bray and Mrs. Linceford were found guilty, as they confessed to the act of adultery and uncleanliness. They were ordered to be whipped and to wear two letters, “AD,” for Adulterers.

In 1651 another adultery case in Maine echoed Hester Prynne’s story. Mary Bacheller, once housemaid turned wife of elderly clergyman Stephen Bacheller, was caught making it with one George Rogers.

Ironically, Magistrate William Hathorne, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s first colonial ancestor (the author added the “w” to his surname), owned a land lot next to them.

The authorities tried to combat the sinful lovers by ordering them to separate, but Mary had got with child and sealed her fate.

As in a scene from The Scarlett Letter, Mary and George were escorted from the stone cell jail and brought before Edward Godfrey, governor of the Providence, and his associate magistrates wearing their high-crown hats on an October day in 1651.

The guilty couple (Mary with her baby bump) stood before the gray-cloaked judges and stern-faced jurors to hear their iron clad sentence.

For George Rogers, the court decreed that he “shall forthwith have forty stripes save one [39 lashes of the whip], upon the bare skin, given him.” Mary’s sentence was also “forty strokes save one, at the first town meeting held at Kittery, six weeks after her delivery, and be branded with the letter A.”

As documented in Yates’ article, there was in fact historical precedent for the punishment Hester Prynne suffered in The Scarlet Letter – Hawthorne didn’t completely make up the plot for his seminal 1850 novel just off the top of his head.

Related Articles: