Introduction: In this article, Mary Harrell-Sesniak tackles one of the most frustrating of genealogy brick walls: why is it that, even though you know you have the right location and year, you cannot find your ancestor listed on the U.S. Federal Census? Mary is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background.

Next time you ponder why an ancestor cannot be located in a particular set of U.S. Census records, consider this: even though you may have the correct location and year, your ancestor could have been overlooked. That may have been due to simple oversight – or perhaps negligence or intentional fraud.

To illustrate, let’s look at the mostly lost 1890 United States Federal Census. In January of 1921, while stored in the Commerce Building in Washington, D.C., about 3/4 of this census was ruined from a fire, water and smoke. Later it was ordered to be destroyed.

All that remain are fragments. Family historians have long rued that event, and thus I looked to newspapers to see if the rumor that many people were not counted in that census was actually true.

Simple Oversight

Was simple oversight a reason?

Turns out there was concern that many people were out of town and missed the count – especially traveling salesmen. This Georgia newspaper article points out another reason: landlords and landladies, who weren’t working from registers, might have been remiss in which tenants they reported.

Negligence

Negligence is commonly alleged for missing records – and we see a number of challenges made to the tallies.

The most widely published report came from the mayor of St. Louis, who felt that there was substantial negligence on the part of the enumerators. The local office disputed this claim, reporting that 99% was correct.

Note: Even if we accept that the figure of 99% accuracy is correct, 1% of errors on the 11th Federal Census is substantial. St. Louis’s population in 1890 was about 450,000, so a 1% error rate would result in over 4,500 mistakes. Extrapolate that to the overall United States population at 62,979,766 in 1890, and perhaps there were as many as 600,000 errors in the 1890 U.S. Federal Census.

Intentional Fraud

To examine this charge, consider the often-overlooked uses of the census — one being to price investments based upon population counts.

An Ohio newspaper article noted that by manipulating population totals, the value of municipal bonds would change by as much as 25%.

Resolutions

What efforts were made to get the count right?

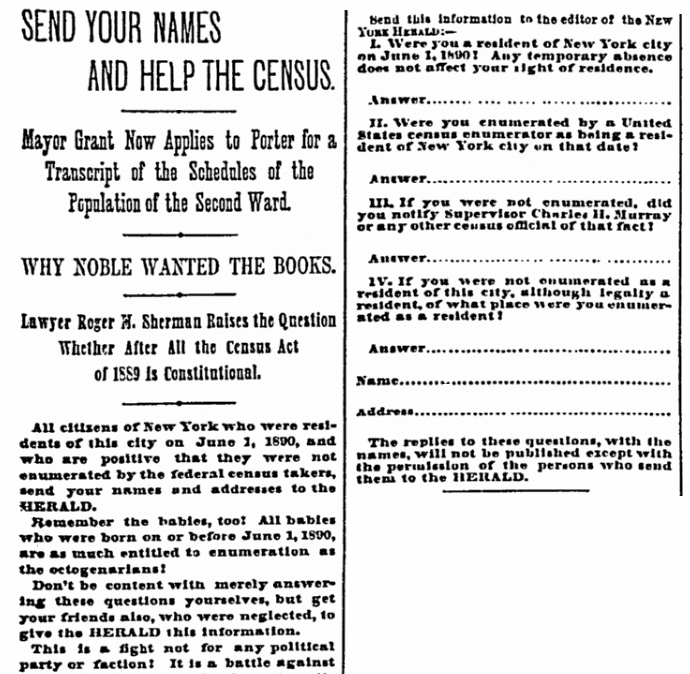

Many areas advertised to get citizens involved if they felt they were not counted. Names were then submitted after the fact to the Census Bureau – and the New York Herald went so far as to publish a submission form.

Have you had success finding your ancestors in the U.S. Federal Census? If so, tell us your stories in the comments section below. And if not, perhaps your ancestor was left off the census for one of the reasons described above.

Related Articles:

On the 1870 census, I looked for my great grandmother, Margaret Cunningham, in Newburyport, Massachusetts. I suspected she had to be there since she immigrated from Ireland to live with relatives who were already there, and she met my great grandfather Patrick in Newburyport some time in 1872 or ’73 and married him in 1875. In the relatives’ household on the ’70 census, I found a “Martha Cunningham.” I knew right away the name had to be wrong; in all my extensive research, I had never come across a “Martha” among the Cunninghams, neither here nor in Ireland, and the Irish were not at all inventive when it came to first names. A little thought about the circumstances surrounding the census gave me a clear picture of what happened: A U.S. marshal — they took the census back then — heard my g-grandmother say “Margaret” with a decided northern Irish accent (she was from Down) and understood “Martha” which is what he wrote on the census.

Always consider the circumstances under which the census data was gathered and try to put yourself in the place of those marshals who’d never talked before with Quebec Frenchmen, Italians, Germans, or Irish natives. You just may discover that relative who was “almost not there.”

John,

You make a good point about names being misunderstood. Thank you.

Mary

My grandfather was not listed in the 1900 census for East St. Louis, Il. His family moved there in 1895 and was listed in the phone books there for 50 years. I couldn’t find any of his neighbors. Finally I went to the local National Archives branch for something else and talked to a very knowledgeable volunteer there. He pulled out the census tract map for East St. Louis and we discovered the census tract boundaries excluded my grandfather’s block. No enumerator was assigned to it, so it was just plain skipped.

Margaret,

Thank you for this feedback. That is another valid reason why people were missed on a census enumeration.

Mary

If I could not find an ancestor in a given census, and I knew the name of someone in the neighborhood, I entered that name. That gave me the correct area of town. Once I found the neighbor, I scanned all of that page, and at least 5 pages ahead and following the initial page. SOMETIMES this worked. If an ancestor lived in a city where City Directories were published, and I found them there, then I could get a correct street name for their residence. It is all a game of chance, but sometimes it pays off.

Joyce,

Thank you for this tip.

Mary

I couldn’t locate my great grandfather and great grandmother in the 1870 census. I looked backward and forward, nothing.

Ann,

Thank you for writing.

It’s possible they were missed, but sometimes family was living elsewhere when the enumeration was taken. For instance, some people moved west and not finding it to their liking, moved back. People also moved temporarily to take care of family.

Mary

I couldn’t locate my grandmother in the 1940 census. She would have been 13 at the time. Her father and brother show as residing with her paternal grandparents, but she’s nowhere to be found. I suspect, at the time the census was taken in her neighborhood, she was staying/visiting with her aunt. Then, when the census was taken at her aunt’s location (neighboring state), she had returned to her grandparents’ home.

Hi Melissa,

Thank you for commenting.

Without direct evidence, we can never know for certain why she was not counted. She may have been with an aunt or another family. Girls often lived with other families to assist with childcare and household duties.

Mary

In searching for my client’s Gleason family in 1870 Chicago, I was able to ascertain that the enumerator had missed 39 dwellings in the space of six days of going door-to-door in the Third Ward. Using the 1870 Chicago city directory, I searched online to find the names of residents living on the same block. My subject lived at 705 State, so I typed the addresses “703 State,” “707 State,” and “705 State.” I got results showing the names of people living at these addresses according to the city directory. Then I did a search for their names in the 1870 census. The results were that several of the neighbors appeared in the census on page 415, but the enumerator was careful to put dwelling numbers in sequence, and one of the dwellings had just a blank space where the names should’ve appeared. Based on the numerical sequence of dwellings on the street, I was able to ascertain that the one dwelling house showing no residents was actually 705 State St., where both my subject -— the Gleason family (2 males and 2 females) — and an Allen Henderson resided. Sure enough Allen Henderson was not indexed in the 1870 census either! Now interestingly, there was published, in 1871, the Edwards Chicago Census Report, which listed both of my missing citizens of 705 State St., along with their ward # and the number of males and females in the household. Apparently the city directory employees followed the census taker on his rounds and managed to get the complete data published in their directory while the census missed them. To investigate just how poorly the enumerator performed, I counted 39 dwellings on 31 pages from the 12th of August to the 17th of August, that were listed with no residents. I estimate he missed somewhere between 10-15% of the population based on my sample.