When asked to name the greatest athletes in U.S. history, most Americans readily identify Babe Ruth and Michael Jordan. However, another name should always be added to that list: Jim Thorpe, arguably the best American athlete of all time. Thorpe’s life was an incredible mixture of triumph and tragedy and reads like a Hollywood script.

In fact, Warner Brothers did make a movie of his life, the 1951 box-office smash Jim Thorpe, All American, starring Burt Lancaster. Being Hollywood, the movie has a happy ending. In real life, Jim Thorpe died unhappy and poor, his health and finances ravaged by alcoholism.

A mixed-race individual of Caucasian and Sac-Fox Native American ancestry, Thorpe was identified as an American Indian all his life. In the second and third decades of the 20th century, his remarkable athletic prowess gained Thorpe fame and adulation, enough victories and records to seemingly ensure a happy, successful life.

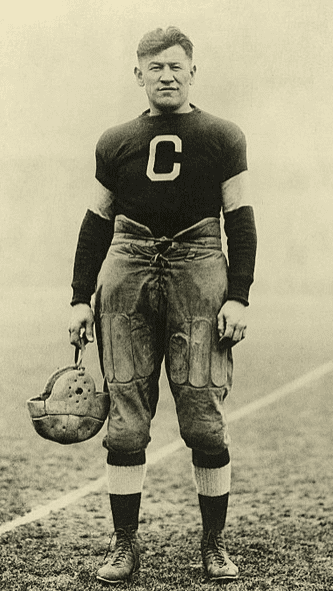

In 1911 and 1912 he won All-American honors playing football for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where he was discovered by famed football coach Glenn “Pop” Warner. He was also the school’s one-man track team, played baseball, basketball and lacrosse, and even won a championship for ballroom dancing!

In the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden, Thorpe won gold medals for the pentathlon and decathlon competitions, prompting King Gustav V to remark “You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world.”

He went on to play professional baseball, football and basketball. He is enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, as well as several other halls of fame: college football, U.S. Olympic teams, and national track and field.

Jim Thorpe’s life was not all accolades and achievements, however. Tragedy stalked him, beginning shortly after his 1912 Olympic triumph: half a year later, the International Olympic Committee stripped him of his gold medals for a minor infraction of its rules. (The medals were restored to Thorpe’s family in 1983, 30 years after his death.)

Four years after his Olympic gold medals were unfairly taken from him, Thorpe suffered an even greater tragedy when his beloved first child, Jim Jr., died of infantile paralysis. The boy was only three years old. Shortly after that, Thorpe’s wife – and sweetheart from his Carlisle days – divorced him. It was the first of two divorces Thorpe would suffer.

He tried to play sports for as long as his body could stand the grind, but finally, in 1929 at the age of 41, Jim Thorpe hung up his cleats for good. What followed were years of misfortune. He never again held a steady job. Alcoholism damaged his health. Despite his third wife trying to make money by promoting Thorpe on a lecture circuit, his finances bottomed out. He had to be accepted as a charity case when he was hospitalized for lip cancer in 1950. After suffering his third heart attack, the 64-year-old Jim Thorpe died in his trailer home in Lomita, California, on 28 March 1953.

After his Olympic gold medals were returned to his family in 1983, the Knight-Ridder News Service produced a two-part newspaper series describing the life of Jim Thorpe, including all the highs and lows. This series was published by the Oregonian on 19 & 20 January 1983.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Medals Dispute Symbolized Thorpe Triumph, Tragedy

First of two parts

By Ray Didinger

Knight-Ridder News Service

LOS ANGELES – The International Olympic Committee presented replicas of two gold medals to the children of Jim Thorpe Tuesday.

The replicas are meant to take the place of the medals Thorpe won in the 1912 Olympics, medals the IOC took away when it learned Thorpe played semi-pro baseball two summers while attending Carlisle College.

The fact that Thorpe earned just $2 a game, not to mention that, in his naivete, he was unaware he was breaking any rules, didn’t matter to the IOC bureaucrats.

They made their decision and stuck to it, stubbornly, for 70 years. Their ruling cast a shadow over Jim Thorpe, a shadow that followed the great Indian athlete to his death in a California house trailer in 1953 and lingers even now.

Tuesday’s ceremony was the culmination of a long fight by the Thorpe family and the Jim Thorpe Foundation to rectify this terrible injustice. Still, it is doubtful the scars ever will heal.

Jim Thorpe was arguably the greatest athlete who ever lived. He set Olympic decathlon records that stood for four decades. He outdistanced Red Grange and Bronko Nagurski in the voting for top football player of the half-century (1900-50).

Thorpe was all of that, yet his life was filled with pain. Three marriages, poverty, drink. He was at once a triumphant and tragic figure.

James Francis Thorpe was born May 28, 1888, in Prague, Okla., in a one-room cottonwood and hickory cabin long since washed away by the floods.

His father was Hiram P. Thorpe, the son of Hiram G., an Irish immigrant fur trapper, and No-ten-o-quah, the granddaughter of Black Hawk, the legendary chief of the Sac-and-Fox nation.

His mother was Charlotte View, a woman of French and Indian (Pottawatomi) descent. She gave her first-born son the name Wa-tho-huck, which meant Bright Path. It proved to be prophetic.

The boy grew up fast and strong. At 8, he bagged his first deer. At 10, he was hiking 30 miles through the woods with his father. At 15, he could rope and break a wild stallion faster than any man on the reservation.

Young Jim happily would have stayed in Oklahoma and worked the land, but his father had other ideas. Hiram Thorpe had heard of this Indian school in faraway Carlisle, Pa., and he was intrigued.

The school was founded by a U.S. Cavalry officer, Lt. Richard Pratt, to educate young Indians in the ways of the white man’s world. In 1904, Hiram Thorpe enrolled his son in Carlisle.

“You are an Indian,” the elder Thorpe said. I want you to show other races what an Indian can do.”

At the time, there were 1,000 students at Carlisle, ranging in age from 10 to 25. They spent half the day in the classroom learning to read and write, the other half in the shop learning a trade.

Thorpe started in tailoring, then, like many students, he was sent out to live and work with white families in the area. He spent two years on a farm in Robbinsville, N.J., tending to the livestock and earning $8 a month.

Thorpe returned to Carlisle in 1907. He did not sign up for varsity sports – he didn’t understand the rules and techniques – but he was curious. So he hung around and watched.

One day, the track team was practicing the high jump. Thorpe came by in his overalls and work shoes. An older boy, jokingly, asked Thorpe if he’d like to try. He cleared the bar on his first jump. No warm-up, no nothing.

The next day, Thorpe was summoned by Glenn “Pop” Warner, the track and football coach. Warner informed Thorpe he had high-jumped 5 feet, 9 inches, breaking the school record.

“I told Pop I didn’t think that very high,” Thorpe wrote later. “Pop told me to go to the clubhouse and exchange my overalls for a track outfit. I was on the track team.”

One month later, Thorpe entered five events in the Pennsylvania Intercollegiate Meet and placed first in all five: the high and low hurdles, the high and broad jumps and the hammer throw.

He won six gold medals in the Penn Relays and the Middle Atlantic Association championships. He had no formal training, his form was crude, yet he won easily.

“There was nothing he could not do,” Warner said.

Well, almost nothing. Thorpe wanted to play football, but Warner wouldn’t allow it. He considered Thorpe too valuable as a trackman to risk losing him with a football injury.

Thorpe kept after Warner until the coach agreed to take him on as a kicking specialist. Thorpe could punt a ball 70 yards and drop-kick a 50-yard field goal, so it wasn’t as if Pop was doing him any favors.

Still, that wasn’t enough. Every day at practice, Thorpe asked the coach to let him run with the ball. This went on for two weeks until, finally, Warner’s patience was at an end.

“All right,” the coach said. “Let’s give the varsity some tackling practice.”

Warner handed Thorpe the ball and he ripped through Carlisle’s first-team defense. Fifty yards. Touchdown.

“Let’s see you do it again,” Warner said.

So Thorpe did it again. As historian Henry Clune recalls, “Tacklers began to hit him, but it was no use. They bounced off and shriveled up behind him, like bacon on a hot griddle.”

Admittedly, it sounds like a scene Hollywood might have written for Burt Lancaster, but it’s true. That’s how Jim Thorpe became Carlisle’s starting halfback, and that’s how the legend began.

For four seasons, Thorpe and the Carlisle Indians were unstoppable. They won 43 games, lost five and tied two. The first seven games in 1912, Thorpe’s final year, Carlisle outscored its opponents 272-15.

The Indians didn’t have a cupcake schedule, either. They played the best: Army, Penn, Harvard, Syracuse, Pitt, Minnesota, Nebraska. And they played them on the road, because they didn’t have a suitable stadium at Carlisle.

Each week, the Indians were outweighed and outmanned – there were only 12 players on the 1911 squad – but that didn’t matter to Thorpe, Jesse Young Deer, Little Boy and the rest.

“Carlisle had no traditions, “Pop Warner once said, “but what the Indians did have was a real race pride and a fierce determination to show the palefaces what they could do when the odds were even.

“It was not that they felt any bitterness against the whites, or against the government for years of unfair treatment, but rather they believed the armed contests between red man and white had never been waged on equal terms.

“On the athletic field, where the struggle was man-to-man, they felt the Indian had his first even break and the record proves they took full advantage of it.”

Jim Thorpe ran up numbers that even now, 70 years later, boggle the mind. In his final season, he led the nation with 198 points. He scored 25 touchdowns and averaged 9 yards every time he touched the ball.

Thorpe was 6-foot, 195 pounds, with 9.8 speed in the 100 and the strength of a world-class shot-putter. He had the physical gifts to be a great running back in any era.

Thorpe was bigger than Tony Dorsett, faster than Earl Campbell, stronger than Walter Payton. He was a 1980s All-American turned loose in the 1910s.

“I’ve seen a lot of great runners,” Hall of Famer George Trafton tells author Robert Wheeler in “Pathway to Glory,” the definitive Thorpe biography.

“I’ve seen George McAfee and Gale Sayers and I’ve played with George Gipp and Bronko Nagurski, but the greatest of them all was Jim Thorpe. The Indian just had something better than all of them.”

It would be redundant to list all of Thorpe’s great games, but two stand out.

The first was the 18-15 win over Harvard in 1911, a game in which Thorpe, playing on a bad ankle, drop-kicked four field goals, including two from 48 yards out, to win it.

Afterward, Harvard Coach Perry Haughton said, “I realized that here was the theoretical superplayer in flesh and blood.”

The following year, Thorpe ran wild in a 27-6 upset of Army. “There is no one like him in the world,” said an awed Cadet halfback named Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Said Pop Warner: “No college football player I ever saw had the natural aptitude possessed by Jim Thorpe. I never knew a player who could penetrate a line as Thorpe could, nor did I know a player who could see holes as well.

“As for speed, none ever carried a pigskin down the field with the dazzling speed of Thorpe. He could knock off a tackler, stop short and turn past another, ward off still another and escape the entire pack.”

It was Pop Warner who signed Jim Thorpe up for the 1912 U.S. Olympic team. Thorpe had never heard of the Olympic Games until Warner told him about them.

Warner told Thorpe this was his chance to compete against the best athletes in the world. Thorpe said that sounded like fun. Pop took care of the paperwork.

The 1912 Games were held in Stockholm. Thorpe was entered in the pentathlon and decathlon. The favorites were Ferdinand Bie of Norway and Hugo Wieslander of Sweden. The Americans, it was said, would be lucky to take a bronze.

The Europeans had no idea what this burly Indian could do, but they soon found out.

Thorpe finished first in four of five pentathlon events. He won the broad jump (23 feet, 3 inches); the 200 meters (22.9); the discus (168 feet, 4 inches); and the 1,500 meters (4:40). He finished second in the javelin.

When the scores were tabulated, Thorpe had tripled the score of the runner-up, Bie.

It was the same thing in the decathlon. Thorpe finished first in four events (shot put, high jump, 110-meter hurdles, 1,500 meters), second in four others (broad jump, 100 meters, 400 meters, discus) and third in the last two (pole vault and javelin).

Thorpe scored 8,413 points out of a possible 10,000, an Olympic record that stood for 20 years. He finished 700 points ahead of the silver medalist, Wieslander.

Recalled Warner: “The wonder and admiration of the onlooking athletes found expression in what came to be a stock phrase, ‘Isn’t he a horse?’”

After the pentathlon, Thorpe went to the awards platform where Sweden’s King Gustav placed a laurel wreath on his head, then presented him with his gold medal and a life-size bronze bust of the king.

After the decathlon, Thorpe returned to the platform. Once again, the King bestowed the laurel wreath and gold medal on him; then the King presented Thorpe with a silver chalice lined with gold, made in the shape of a Viking ship.

What happened next is the most enduring memory of all: Gustav clasped Thorpe’s hand and, totally blowing his royal cool, said, “Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world.”

“Thanks, King,” Thorpe replied.

Thorpe’s answer was lacking in formality, perhaps, but not in feeling. A king had called him “sir.” It was a moment the young Indian would cherish forever.

Next: Life after the Olympic pinnacle.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Personal Misfortune Stalked Thorpe after Olympics

Second of two parts

By Ray Didinger

Knight-Ridder News Service

LOS ANGELES – Jim Thorpe returned home from the 1912 Olympic Games to a hero’s welcome. He was hailed by the president. Parades were held in his honor. Fifteen thousand people came to Carlisle’s Biddle Field to salute him when he arrived in his open carriage.

Some say the post-Olympic scene was what messed up Thorpe’s life. A classic case of too much too soon. Poor Indian boy, in over his head. That’s not entirely true.

Thorpe, 24, already had tasted national acclaim as a football player. He wasn’t really comfortable in the spotlight, but he wasn’t bowled over by it, either.

No, what turned Jim Thorpe’s world upside down was a series of personal tragedies, the first being the loss of his two gold medals. How Thorpe was found out is a book unto itself.

It seems a Worcester, Mass., newspaperman was interviewing Charley Clancy, the manager of the Rocky Mount, N.C., baseball team, in January 1913. Quite innocently, the reporter noticed a framed photograph of Clancy and several players returning from a hunting trip.

He immediately recognized one of the players as Jim Thorpe. He asked what Thorpe was doing with the team. Clancy couldn’t lie. He told the reporter Thorpe had played two summers in Rocky Mount.

The story made national headlines. Thorpe wrote a letter of apology to the American Olympic Committee, explaining he was “not wise in the ways of the (athletic) world.”

It was no use. Despite an outcry from journalists and sportsmen around the world, the AOC stripped Thorpe of his medals and wiped his name from the Olympic record books.

Thorpe took the news in his customary stoic fashion, but he was deeply hurt. Years later, he awoke his New York Giants roommate, the Indian catcher, Chief Meyers, tears rolling down his cheeks.

“The King of Sweden gave me those trophies,” Thorpe told Meyers, “but they took them away. They’re mine, Chief. I won them fair and square.”

“It broke his heart,” Chief Meyers said in Lawrence Ritter’s book, “The Glory of Their Times.” “He never really recovered.”

Thorpe’s other personal tragedy came in 1917 when his first child, Jim Jr., died of infantile paralysis at the age of 3.

The boy was Thorpe’s pride and joy. The two were inseparable. Thorpe seldom displayed emotion in public, but he was openly affectionate and loving with Jim Jr.

“I remember spring training 1917,” former Giant Al Schacht told Wheeler. “After practice, they’d be on the lawn in front of the hotel. The kid would climb up one of Jim’s arms and down the other and he’d grin that big, wide grin just like his old man. The two of them would laugh.

“After his death, Jim was never the same.”

It wasn’t long after that Iva Miller Thorpe, Jim’s wife and Carlisle sweetheart, divorced him. He was more alone, more unhappy than ever.

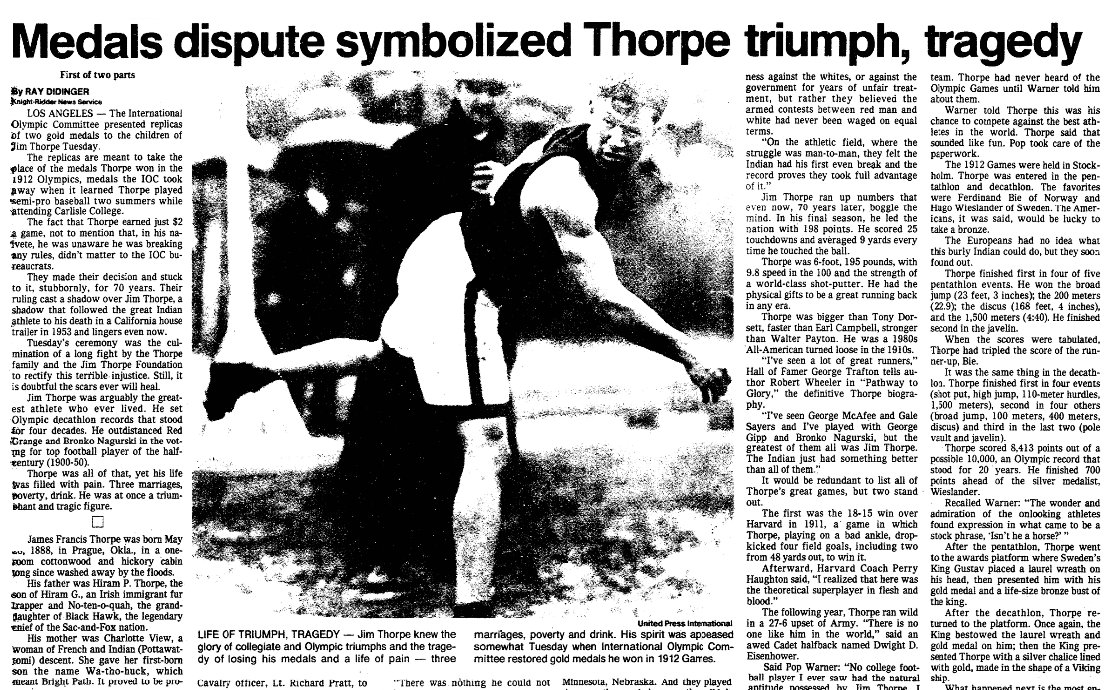

Jim Thorpe signed with the New York Giants after leaving Carlisle in 1913, mostly because there wasn’t much else to do.

He had offers from vaudeville agents: $1,000 a week for performing feats of strength on the stage. And he had a few calls from California. Something about “moving pictures,” whatever they are.

But Thorpe knew he belonged on the playing field, not the stage. Baseball wasn’t his best sport, but it was the only one that paid a living wage back then, so he signed. Three years, $6,000 a year.

Thorpe would have been better off with another team. The Giants were the National League champions. They didn’t need a rookie outfielder, but Thorpe wasn’t just any rookie outfielder.

“If he can only hit in batting practice, the fans that will pay to see him will more than make up for his salary,” Manager John McGraw said.

In other words, Thorpe was a drawing card, strictly an ornament. He went to bat 35 times that year. He managed five hits, a .143 average.

Thorpe grew restless. He hated riding the bench. He feuded openly with McGraw, better known as “Little Napoleon.”

One day, Thorpe missed a sign while running the bases. McGraw called him “a dumb Indian.” Thorpe chased McGraw through the dugout. It took half the team to restrain him. Thorpe was sold to Cincinnati the next day.

Thorpe played regularly in Cincinnati and proved he belonged in the major leagues. By 1919 he had raised his average to .327, but he was looking for other mountains to climb.

A professional football league was forming in the Midwest and Thorpe became involved. Football always was his first love, of course.

Thorpe signed with the Canton Bulldogs for $250 a game. He was well worth the investment. He gave the new league credibility. It would be like Herschel Walker signing with the U.S. Football League today.

Without Thorpe, the Bulldogs were drawing 1,200 fans a game. With Thorpe, they filled the 8,000-seat stadium in Massillon.

Thorpe still was in fine form and led Canton to several unbeaten seasons. With his name on the marquee, professional football took a firm hold on the American scene.

Thorpe remarried and, with this second wife, Freeda, he had four children.

But then, as Thorpe got older, the grind got tougher. He left the Bulldogs and bounced around. Nine teams in seven years. Rock Island, St. Petersburg, Portsmouth…

For a while, he barnstormed with some former Carlisle players. The team was called “Jim Thorpe’s Oorang Indians.” They were sponsored by the Oorang Airedale Kennels in LaRue, Ohio.

Thorpe finally hung up his cleats in 1929 at the age of 41. He tried to find another line of work, but it wasn’t easy.

For a while, he was master of ceremonies at Charlie Pyle’s “Bunion Derby,” a cross-country marathon race, but the show went bankrupt. Thorpe finally had to sue Pyle for his $50 paycheck.

He worked as a painter, then a construction worker at 50 cents an hour. He picked up a few bucks as a stunt man at MGM. His life was falling apart again. He was drinking and money was scarce.

In 1932, the Olympic Games were held in Los Angeles and Thorpe couldn’t afford a ticket. Word got out and Vice President Charles Curtis, an American Indian, decreed the former champion would sit in his private box while he opened the Games.

The Coliseum crowd of 105,000 gave Thorpe a standing ovation. It was very nice and very touching, but, like everything else, it passed quickly. Soon, Thorpe was back in the real world, fighting to survive.

In 1941, Freeda sued Jim for divorce, claiming he was gone for weeks at a time. Jim explained that was the nature of Indian men. Perhaps, but he wasn’t living on the reservation anymore. Freeda got her divorce.

When World War II broke out, Thorpe tried to enlist in the Marines, but, at 53, he was turned down. He signed on with the Merchant Marine and sailed to India aboard the U.S.S. Southwest Victory.

When he returned, Thorpe married for the third time, this time to Patricia Askew, a hardnosed businesswoman who took over his affairs. She actually turned Jim Thorpe into a money-making enterprise, although she stepped on a few toes along the way.

She began charging $500 plus expenses for her husband’s personal appearances. Prior to that, Thorpe had done his appearances for nothing. He even paid his own way back and forth.

Pat changed all that. She lined up a lecture tour that covered 67,000 miles in one year. It was exhausting, but profitable. She later added Indian dancers and singers to the act.

In 1951, Warner Brothers released the film, “Jim Thorpe, All-American,” with Burt Lancaster in the title role.

The movie was a box-office smash, but Thorpe saw none of the profits. It seems he unwittingly signed away the screen rights to his own life story 20 years earlier. The price: $1,500.

“That was a mistake,” Thorpe admitted.

On March 28, 1953, Jim Thorpe suffered a fatal heart attack while eating dinner with his wife in their house trailer in Lomita, Calif. He was 64.

Years later, Wilbur J. Gobrecht wrote: “Jim Thorpe’s was not a happy or successful life. Maybe he used up his quota of happiness and success as an athlete and had nothing left afterward. It would seem so.”

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. The same is true of more recent news.

What a GREAT NATURAL ATHELETE AND NATIVE AMERICAN SO COOL HIS FAMILY SHOULD BE SO PROUD WHAT A GREAT MAN

So very tragic that a Native American and gifted athlete, a true credit to his country, received such ill treatment from the Olympic committee. Shame on each member who voted to strip his record and medals. I am a native Pennsylvanian who has visited Mauch Chunk, now Jim Thorpe, PA, many times as my family was from the region. While having his remains in PA was felt to be something that would bring tourism to the towns that consolidated to make Jim Thorpe a town, morally his remains belong home in Oklahoma, and I pray his family succeeds in this quest someday. If any place in PA had a right to claim him, which it did not, it would have been Carlisle. He was an amazing athlete, and so gifted, and held high praise so long as he was able to bring glory to his teams, all of which seem to have deserted him when he left sports. What a shame. A true friend never deserts someone. Bravo to Burt Lancaster for his movie performance as Jim. A movie about a real person succeeds when it makes you want to know more about that individual and I have spent the afternoon reading articles about him. What an amazing man. I wish I had had the opportunity to see him play but I was only a few years old when he died. Rest easy, Jim, and run to your heart’s desire.

Thanks, Nancy; nice tribute.

What a beautiful and sincere and heartfelt tribute to the greatest American athlete ever Jim Thorpe! Thanks so very much Nancy Schaub!

I feel exactly as Nancy Schaumburg! Taking away Jim’s medals was so tragic and heartless to do to a man who had worked so hard for himself and the glory of his country! None of these men would have had the grit, stamina, or the ability to do what Jim did, but they did know how to knock down a truly amazing great man!!!

Thanks for your strong comment, Peggy.

A great American Indian and how the U.S. government pushed him aside… like he said, he didn’t understand the rules. If no one told me I’d have done the same thing. They really wanted a white man to win. He’s still my hero, I don’t care what anybody says.

He’s a hero to a lot of people, Donald — and rightfully so.

Jim Thrope is the great athlete, not just a great native American athlete,even greater than Babe Ruth himself. The take the gold away from the man a King called the world’s greatest athlete is shameful. I bet if he was white instead of native American he’d have kept his gold. I’ve visited the pathetic excuse for a monument in Mauch Chunk. If that’s the best they can do, then allow his family to bury him where he belongs, with his ancestors back in Sax and fox nation. Most of the people in Mauch Cunk I asked for directions to his tomb, couldn’t even tell me. Just sad.

Tony: I just read the Jim THORPE biography by a lady writer from Westchester, New York.

2010…I believe. Her surname was Burton.

It was good.

Check it out. 2010.

Thanks for the recommendation, Craig; I will check it out.

The Olympic committee has never reinstated his records. Yet today there’s no such thing as amateur in the Olympics.

Is that true, Dan? If so, what a shame. They returned his medals — why not return his records as well? Thanks for writing and letting us know.

We are trying to confirm his Merchant Marine service in WWII, I am with the American Merchant Marine Veterans. The US Merchant Mariners of WWII have been Awarded the Congressional Gold Medal of 2020, for their service in WWII. You stated he served on the USS Southwest Victory, we believe it may have been the SS Southwestern Victory as USS Ships were Navy Ships and the Victory ships were SS. Please let me know, how and where you got the ship name and any information you may have on his WWII service

Hi Thomas,

I wish I could confirm this info for you, but I actually didn’t write it. The information about Jim Thorpe’s WWII service in my blog article is a transcription of a newspaper article Ray Didinger wrote for the Knight-Ridder News Service, published in the Oregonian newspaper (Portland, Oregon) on 20 January 1983, page 82. Perhaps Knight-Ridder, and maybe the Oregonian itself, can tell you how to get in touch with Ray Didinger. Good luck with your research!

–Tony Pettinato

Thomas: I am searching for information about Jim Thorpe’s Merchant Marine service in WW II, and hope you

will send me as many specifics as you have unearthed. I will credit you with all information you provide in any

publications I author or co-author. If you have any questions, communicate, please. Thank you for any help you provide.

Dr. Bob Reising

Professor Emeritus: UNC Pembroke

rreising54@gmail.com

Conway, Arkansas

Tony,

I am glad that you did not write it because Ray Didinger is incorrect. I was able to find the ship’s crew list on ancestry and it actually has the SS Southwestern Victory ship and Jim Thorpe is listed as age 56 and a carpenter on the ship. I will research the author to see if he is still able to correct this. If you wish to see the crew list I’d be happy to share it with you since I am giving you my email address. Sheila S.

Thanks for your follow-up research, Sheila. You don’t have to send me the crew list; I believe you.

The performance by Burt Lancaster was stellar but it doesn’t show how hard it was for the Indians to even exist in this country. The persecution still goes on to this day. God bless all the Indians who roamed all the nation and tried to live a peaceful existence with the white men.