The fall of Mexico City on 14 September1847, to American troops led by General Winfield Scott, was the decisive blow that gained victory for the United States in the Mexican-American War. With all of its major cities occupied, Mexico had to accept the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on 2 February 1848, ending the war.

This treaty transferred a huge swath of territory to the United States, including all of the present-day states of California, Nevada and Utah, as well as parts of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming.

The war with Mexico – precipitated by America’s annexation of Texas – created controversy even as it began, with members of the public and press questioning its justification; some saw it as little more than an American land grab.

The fall of Mexico City began with the American capture of a castle on a hill overlooking the city, called the Battle of Chapultepec, on 13 September 1847.

In 2010, on the 163rd anniversary of that battle, Mexican President Felipe Calderon referred to the war as an “unjust military aggression motivated by clearly imperialistic interests.” Some Americans in 1846-48 would have agreed.

After Scott captured Mexico City, the Boston Daily Times published an interesting article about the battle: a translation of a letter written by a Mexican, presenting a perspective few Americans see.

Here is a transcription of this article:

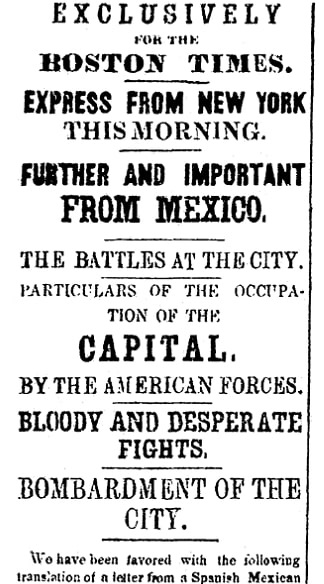

Exclusively for the Boston Times.

Express from New York This Morning.

Further and Important from Mexico.

The Battles at the City.

Particulars of the Occupation of the Capital by the American Forces.

Bloody and Desperate Fights.

Bombardment of the City.

We have been favored with the following translation of a letter from a Spanish Mexican from the city of Mexico to a Spanish house in this city. The letter came via Orizaba under cover of Mr. Dimond, American Collector of the city of Vera Cruz. The news it gives is more full than we have received from any quarter, but it bears a Mexican face, for which allowance must be made. It however sufficiently proves that Mexico is reduced to the last extremity.

City of Mexico, 19th Sept., 1847

Respected Friends: I have an opportunity to send by the courier who leaves tonight this letter, in which I shall briefly attempt to describe to you the horrors we have just experienced. On the 7th instant our commissioners rejected the treaty propositions of the American Government, and decided on resuming the war, Gen. Herrera inviting and urging the clergy to rouse the citizens to the utmost resistance. On the same day General Scott, the American Chief, charged Santa Anna with breaking the armistice by forbidding his commissioners to obtain food in the city, and threatened, unless reparation was made, to commence hostilities and bombard the city. Santa Anna replied severely, charging Scott with breaking the armistice by sacking our villages, and expressed his perfect readiness to renew the war. On the 13th inst., the Americans made a demonstration on Chapultepec and the Mill of El Rey, but our generals were prepared for them. Anticipating a breach in the armistice, Santa Anna for several days had caused to be conveyed in every possible manner so as to not excite suspicion, arms, munitions and food to the fortress of Chapultepec. Our citizens carried under their mantles and on mules a great quantity of powder, balls and provisions, without being once discovered, so great was the feeling of security and confidence among the Americans. Gen. Scott was not a little surprised to find on attacking Chapultepec such obstinate resistance. Chapultepec, you know, is situated between Tacubaya and the city, within cannon-shot of the former, and some three miles from the latter. It is a bold hill overlooking a vast range of country, which enabled our soldiers to watch every maneuver of the enemy. It also commands the road from Tacubaya to the city, which runs close by its base, and it can only be ascended by a circuitous paved way, which, after turning a certain angle, is exposed to the full range of the fortress guns. As the Americans ascended the hill, a perfect storm of musket ball and grape shot drove them back with heavy loss.

They recovered and advanced again, but were repulsed. Our troops fought with desperate valor, worthy the character of Mexicans. The enemy also fought bravely; his men seemed like so many devils whom it was impossible to defeat without annihilation. He made a third and last charge with fresh force and heavy guns, and our gallant troops having exhausted their grape shot were forced very unwillingly to retreat and yield up the fortress of which the enemy took possession. Our soldiers retreated towards the city, but were unfortunately cut off by a detachment of the enemy’s cavalry, and about 1000 were made prisoners, but were very soon released as the enemy had no men to guard them. The enemy then opened his batteries on the Mill El Rey (King Mill) close upon Chapultepec, which after obstinate fighting and great loss to the Americans, we were obliged to abandon. The two actions continued over nine hours, and were the severest, considering our small number of soldiers and the enemy’s large force, that have been fought. Our loss in killed and wounded was not more than 300, while the enemy lost over 400, or at least such was the report of deserters from the American camp, who came to us in the evening. Seeing that the city would inevitably be attacked, Gen. Santa Anna, during the actions, caused a number of trenches to be cut across the road leading to the city, which were flooded with water.

On the morning of the 14th, before daylight, the enemy, with a part of his force, commenced his march upon the city. Our soldiers, posted behind the arches of the aqueducts and several breastworks which had been hastily thrown up, annoyed him so severely, together with the trenches which he had to bridge over, that he did not arrive at the gate until late in the afternoon. Here he halted and attempted to bombard the city, which he did during the balance of the day and the day following, doing immense damage; in some cases whole blocks were destroyed, and a great number of men, women and children killed and wounded. The picture was awful; one deafening roar filled our ears, one cloud of smoke met our eyes, now and then mixed with flame, and amid it, all we could hear was the various shrieks of the wounded and dying. But the city bravely resisted the hundreds of flying shells, it hurled back defiance to the bloodthirsty Yankee, and convinced him that his bombs could not reduce the Mexican capital.

The enemy then changed his plan, and determined to enter the city, where we were prepared to meet him, having barricaded the streets with sandbags, and provided on the housetops and at the windows all who could bear arms or hurl missiles, stones, bricks, &c., on the heads of the enemy. Before General Scott had fairly passed the gates he found the difficulty of his position. A perfect torrent of balls and stones rained upon his troops. Many were killed and more wounded. Still he kept advancing until he gained the entrance of two streets leading direct to the Plaza.

Finding that he could not oppose himself to our soldiers, who were all posted out of sight, and that he was losing his men rapidly, Gen. Scott took possession of the convent of San Isidor, which extends back to the centre of a block, and at once set his sappers and miners to cutting a way directly through the blocks of buildings.

In some instances, whole houses were blown up to facilitate his progress; but after several hours he again emerged into the street, and finally regained the Plaza with great loss. On entering the Plaza a heavy fire was opened on him from the Palace and Cathedral, which were filled and covered with our patriotic troops. Finding himself thus assaulted, the enemy drew out his force in the Plaza and opened a cannonade on the Palace and Cathedral, firing over one hundred shots, which did immense damage to the buildings, and caused a severe loss of killed and wounded. Seeing further resistance useless, our soldiers ceased firing, and on the 16th of September (sad day!) the enemy was in possession of the Mexican capital. Though we inflicted havoc and death upon the Yankees, we suffered greatly ourselves. Many were killed by the blowing up of the houses, many by the bombardment, but more by the confusion which prevailed in the city, and altogether we cannot count our killed and wounded and missing since the actions commenced yesterday, at less than 4000, among whom are many women and children. The enemy confesses a loss of over 1000; it is no doubt much greater. What a calamity! But Mexico will yet have vengeance. God will avenge us for our sufferings. Alas that I should write this letter within sight of a proud enemy who has succeeded by his ferocity in trampling on our Capital and our country.

An enemy who only prides himself upon shooting well with his rifle and cannon. But thus it is – we are prostrated – not humbled. We may be forced to silence, but the first moment that presents us a chance will be devoted to terrible revenge.

Santa Anna has gone with his generals and all the troops he could draw off to Guadalupe. He is said to be wounded severely. We have lost heroic officers and brave men in these two days. I cannot foresee what is to come. Thousands are gathering upon the hills and around the city, determined to cut off all supplies, and starve the enemy who has so audaciously entered it.

Gen. Scott may yet find that Mexico is not vanquished. He may find our lakes bursting their barriers and filling the beautiful valley to annihilate the infamous Americans. We scarcely hope, yet we do not despair. Our brave generals may recover what is lost, and Mexico with her ten millions of people arise to sweep the invader from the land he has desecrated. Be sure that whatever we do in the way of submission is only for the moment. No Mexican will respect beyond the hour that forces him to it, any bond dictated by the sword of an enemy. My heart is too full of grief and indignation to write more. Adieu.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in the Mexican-American War? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Articles: