Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry presents part two of her story about the first two Quakers (Ann Austin and Mary Fisher) to arrive at the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

“About this time many friends went beyond the sea, to declare an everlasting Truth of God.”

–George Fox, founder of the Quakers

My last story covered the two Quaker missionaries, Ann Austin and Mary Fisher, who sailed aboard the Swallow from the Barbados to Boston in July of 1656. Captain Simon Kemperthorn, master of this vessel, agreed to offer safe passage to the two Quakeresses – which was arranged by John and Thomas Rous, wealthy merchants from Barbados. Today I’m going to provide more details.

To recap: The arrival of Austin and Fisher sent the Puritan officials into a tizzy. The authorities found in the women’s trunks the “most corrupt, pernicious, heretical, blasphemous doctrines” contrary to the beliefs set forth by the Puritan church. Their books were seized and burned. Austin and Fisher were apprehended.

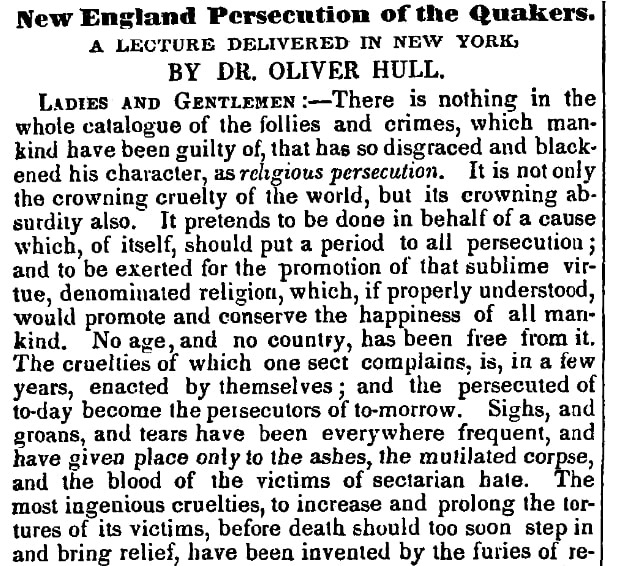

In 1852 the Boston Investigator published “New England Persecution of Quakers,” a lecture given by Dr. Oliver Hull in New York. Hull retells the account of Austin and Fisher, as well as other Quakers who suffered persecution in New England.

Hull’s opening statement condemned religious persecution. He issued a warning to all societies: all must learn from history, or they are surely doomed to repeat it. He then stated:

“The early settlers in this country, fleeing from persecution, very soon became themselves persecutors. The sound of their complaints had hardly died from their lips, before they began themselves to persecute the mildest, and most inoffensive of all sects – the Quakers.”

Hull said in his lecture:

“In July [1656], two women [Ann Austin and Mary Fisher], preachers of the sect of Quakers, arrived in Boston harbor from Barbados. As soon as their arrival was known, the Deputy Governor, Bellingham, sent officers on board the vessel to search their trunks, for heretical publications. They took about one hundred books and pamphlets from them, and carried them on shore. An extraordinary council was convened on this alarming occasion, which, on the 11th of July, fulminated an order by which, after reciting that these two women, ‘being of that sort of people commonly known by the name of Quakers,’ ‘holding very dangerous, heretical, and blasphemous opinions;’ and also acknowledging ‘that they came here purposing to propagate their said errors and heresies; bringing with them and spreading here sundry books wherein are contained most corrupt, heretical, and blasphemous doctrines, contrary to the truth of the gospel here professed amongst us,’ ordered the books to be burned by the hangman, and the women to be imprisoned. They remained in prison about five weeks, and were then put on board a vessel going to Barbados, and sent away.

“Whilst they were in prison, their Puritan keepers, being influenced by a superstitious belief in witchcraft, or some other motive, stripped them naked to search for witch tokens. These witch tokens were any insensible spot, ascertained by thrusting a pin into the flesh; any apparent teats at which the devil might suck; or any other unusual mark, which the superstition or the fancy might take for a token that the bearer was a witch. Gough, from whose history of the Quakers I take this account, says: ‘They misused them, in this search, in a shameful and barbarous manner.’”

Sounds like Salem in 1692, when town officials commonly practiced witch mark searches.

Hull went on to explain that shortly after the two women were exiled, eight more Quakers arrived in Boston from London: four men and four women. Like Austin and Fisher, these eight were imprisoned and their books seized and burned. Hull said:

“It may be asked if there was no one of gentle spirit enough to befriend these unresisting Quakers, to shed the tear of pity, and to endeavor to bind up the broken heart? Yes; such a person was Nicholas Upshall, an old man, and a member of the Boston church. He furnished them with food, and protested against the cruelty of their treatment. For this, he was fined twenty pounds, and finally banished during the winter. He was however kindly received by an Indian chief in Rhode Island, who expressed his wonder at the notion the English nation must entertain of the Divine Being, ‘as they dealt so cruelly with one another about their God.’”

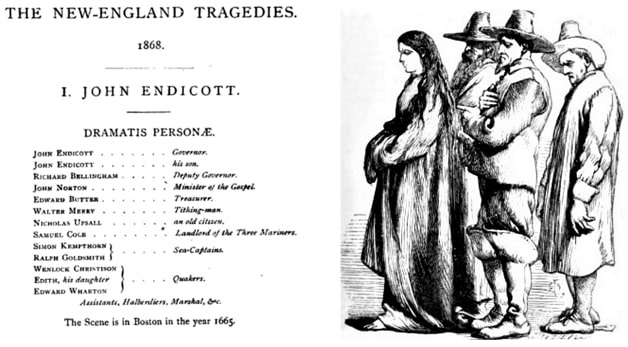

Nicholas Upshall appears as a character in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1868 work “The New-England Tragedies,” a long poem consisting of two dramas. Other characters include Quakers who were persecuted in New England by Governor Endicott and the courts.

Longfellow’s theme was the same Hull lectured on: the early settlers in this country, fleeing from persecution, very soon became themselves persecutors.

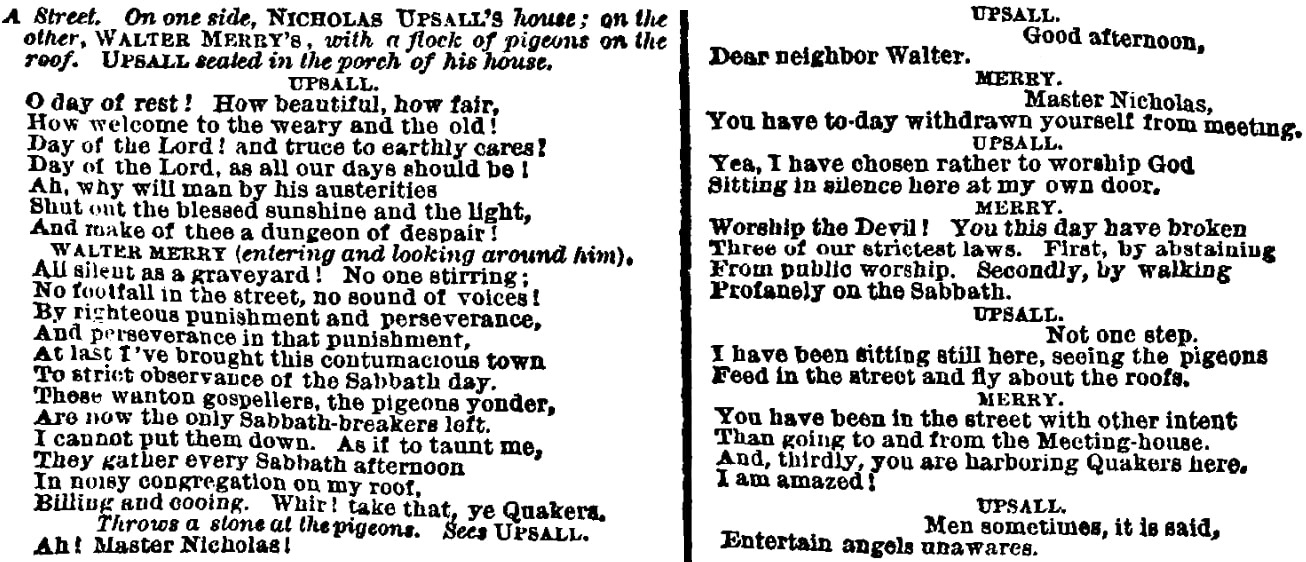

When The New-England Tragedies was first published in 1868, the New-York Semi-Weekly Tribune published portions of the long poem, including this segment in which Upshall (spelled “Upsall” in the poem) is accosted by Walter Merry, a town official, because he is lounging on his porch on the Sabbath Day. Everyone was supposed to be inside their homes or walking to or from church service on that day – a strict requirement that Merry has worked strenuously to enforce.

Interactions with the Quakers in 1656 led to stringent laws enacted by the Puritan courts. As Hull detailed in his lecture:

“Several laws were passed at the ‘General Court, held in Boston,’ against the Quakers, of which two or three specimens may be interesting. On the 14th of October, 1657, it was ordered ‘that if any person should entertain any Quaker or Quakers, or other blasphemous heretics,’ they should be fined forty shillings for every hour of such entertainment; and ‘if any Quakers should presume, after they had once suffered the law, to return into their jurisdiction, if a male, he should have one of his ears cut off for the first offence, the other ear for the second offence; if a female, to be severely whipped for the first offence, the like punishment to be repeated for the second. For the third offence their tongues to be bored through with a hot iron.’ In October, 1658, another law was passed ‘that every person of the cursed sect of Quakers shall have a legal trial by a special jury, and being convicted to be of the sect of the Quakers, shall be sentenced to be banished upon pain of death.’”

Note: Just as an online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, helped tell the stories of the Puritans and the Quakers, they can tell you stories about your ancestors that can’t be found anywhere else. Come look today and see what you can discover!

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: a Quaker tapestry devoted to Mary Fisher. Courtesy of Patheos.com from “Great Quaker Women: Mary Fisher, Jailed Repeatedly for Preaching.”

Related Articles: