Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry tells the story of two men who carefully observed the transit of Venus across the Sun in 1769. Melissa is a genealogist who has a website, americana-archives.com, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

The West Newbury, Massachusetts, country estate “Spring Hill,” built by Captain Michael Dalton and his wife Mary (Little), was a pastoral paradise. The poesy of French revolutionary and journalist Jacques Pierre Brissot “de Warville” deemed Spring Hill “one of the most beautiful spots imaginable.”

When their son, U.S. Senator Tristram Dalton (1738–1817), took charge of the Dalton House, it grew even more glorious. Dalton and his wife Ruth Hooper, daughter of wealthy merchant Robert “King” Hooper, knew how to throw a party. Their festive soirees hosted notables like George Washington, John Adams, and an ensemble of French royals. Visitors from all over the globe enjoyed Spring Hill’s enchanting landscape and breathtaking views.

In late spring of 1769, there was a celebrated guest summoned to the Pipe Stave Road address who would observe with Dalton a different sort of visitor, an extraterrestrial one: Venus.

Samuel Williams, Harvard professor of mathematics and natural philosophy, was more than happy to make the observation with Dalton; he knew “a seat at Newbury, in a high elevated situation,” was “very convenient for this purpose.”

From a vantage point upon the hill could be viewed “40 mountain peaks and oceans far and wide.” It was the most auspicious place to observe the celestial heavens. God had even graced Spring Hill with 18 church steeples in a wide view.

But this gathering in 1769 was not just for idle star gazing: it was to expand scientific knowledge by observing the transit of Venus across the Sun – a rare celestial event, visible from Earth, that happened twice in the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, and not at all in the 20th century. It has already happened twice in the 21st century, and won’t happen again until 2117.

Dalton had a keen interest in the field of astronomy and was part of the newly founded American Academy of Arts and Sciences. To observe the transit of Venus, Dalton chose his partner carefully.

Williams had been selected by Harvard’s John Winthrop to observe the transit of Venus during the Newfoundland expedition of 1761. His lectures and experiments were progressive; when Williams preached in Newburyport, Dalton sought him out.

Williams matched Dalton’s passionate intensity to explore the “dark horses” of the world. Williams excelled in many diverse disciplines and his innovative style earned him honors. More importantly, Dalton knew that besides Winthrop, Williams “was among the most accurate of any estimating the moment of tangency of the internal contact to the Sun which had an uncertainty of only seven seconds.”

Williams had the same confident spirit working with Dalton, and knew he was well versed in theory from his Harvard days – and would be an active participant in assisting him. Dalton’s knowledge allowed him to make necessary preparations in advance, such as getting the clock adjusted and longitude determination made.

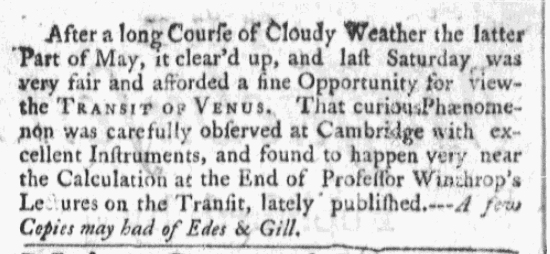

Dalton also took all precautions, which included hiring carpenters to build shelters on the roof so that they could safely observe the transit. A persistent trend of overcast skies and rain had set over Newbury, but just before the big event Mother Nature decided to cooperate. The conditions could not have been more perfect, as one Boston paper reported:

“After a long Course of Cloudy Weather the latter Part of May, it clear’d up, and last Saturday was fair and afforded a fine Opportunity for viewing the Transit of Venus.”

The challenge confronting the observers was in calculating the exact time to observe the “black dot,” or Venus, crossing in front of the Sun. However, Williams was successful – and he carefully recorded the planetary activity and discovered that Venus had a definite atmosphere. He reached this conclusion due to the “fuzzy contrast” and “uncertain timing” he observed during the transit. In other planets’ transits across the Sun, such as Mercury, the observation was precise and easily timed. William’s revelation would go unrecognized at first, but a few years later was noted as a significant discovery.

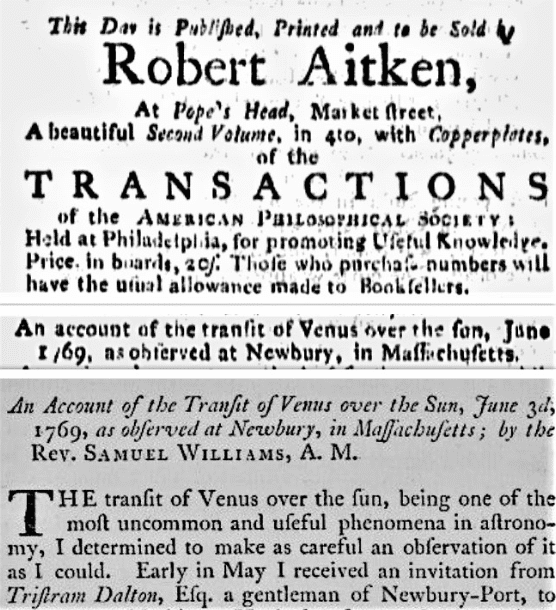

The transit of Venus produced “an intercolonial scientific effort of major proportions” and there were several locations observing the event, but it was Newbury that caught Benjamin Franklin’s attention. His organization, known as the American Philosophical Society, issued Williams’s publication An Account of the Transit of Venus over the Sun, June 3d, 1769, as Observed at Newbury, in Massachusetts.

Williams’s work impacted several scholars, including John Quincy Adams, who attended his series of 24 lectures on astronomy at Harvard. According to Rothschild, Adams was “so engrossed with the subject that he wrote copious notes on the lectures during and after their presentation.”

The warm affinity and respect Adams had for Williams sustained a relationship for many years, and he was equally fond of Williams’ son, Samuel Jr., who was his classmate at Harvard. During his stint in the Port, Adams recorded dinners with Samuel Jr., and some visits to Dalton’s magical manor on the hill.

The contribution of Williams and Dalton’s observations of the transit of Venus reflected a lifetime of reaching for the stars and encouraging others to expand their horizons.

The grounds at Spring Hill have been torn down and rebuilt since the Dalton reign. Tristram invested in new territory, but calculated risks took his fortune. The planets taught this explorer that Heaven is not down on any map; true places never are.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Sources:

- Brissot “de Warville,” Jacques Pierre. New Travels in the United States of America, 1788. Translated by Mara Soceanu Vamos and Durand Echeverria. Edited by Durand Echeverria. Cambridge, Mass., 1964.

- Rothschild, Robert Friend. “Two Brides for Apollo: The Life of Samuel Williams (1743-1817)” iUniverse, Inc., Bloomington, Indiana 2009.

- Samuel William Papers, University of Vermont Libraries. Special Collections Bailey/Howe Library, Burlington, Vermont.

- “John Adams to John Quincy Adams, 3 June 1786,” Founders Online, National Archives.

- Essex Institute Collections. “The Letters of Tristram Dalton.” Volume 71. Essex Institute Press, Salem, MA. 1935.