Juneteenth, a uniquely American holiday, celebrates the declaration by Union Army General Gordon Granger on 19 June 1865 in Galveston, Texas, that “all slaves are free” – the last remaining slaves of the Confederate States of America were finally liberated.

President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect 1 January 1863 – but two and a half years later, there were still slaves in Texas. Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered on 9 April 1865 – but two months later, there were still slaves in Texas. Next month, the Confederate Army of the Trans-Mississippi, which included Texas, surrendered on May 26 – but there were still slaves in Texas.

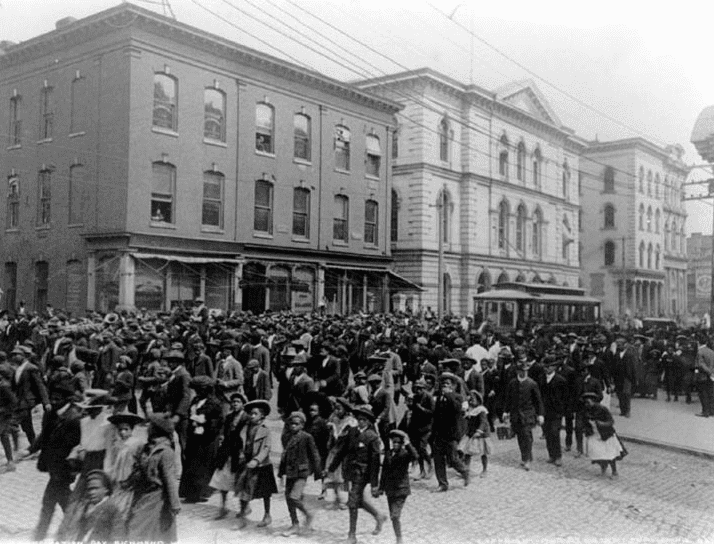

Then General Granger arrived in Galveston with federal troops to occupy Texas. On 19 June 1865, he climbed to the balcony of Ashton Villa, a brick house in Galveston that had served as the headquarters of the Confederate Army, and announced “General Order No. 3” freeing the slaves. The Civil War was over, and all the Confederacy’s slaves were free at last.

Note that General Granger’s proclamation, while freeing the slaves, nonetheless stated that they should remain on the plantations that enslaved them – only now, they were to be paid for their labor.

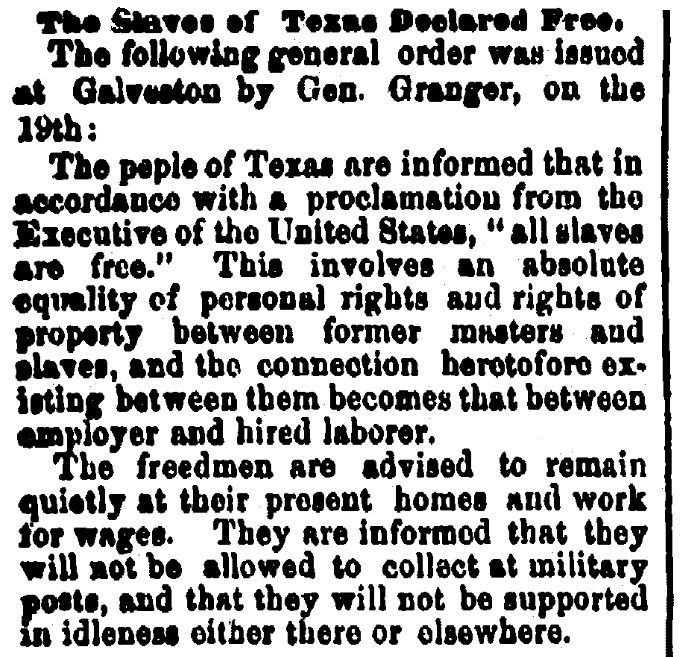

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Slaves of Texas Declared Free.

The following general order was issued at Galveston by Gen. Granger, on the 19th:

The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, “all slaves are free.” This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.

The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts, and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

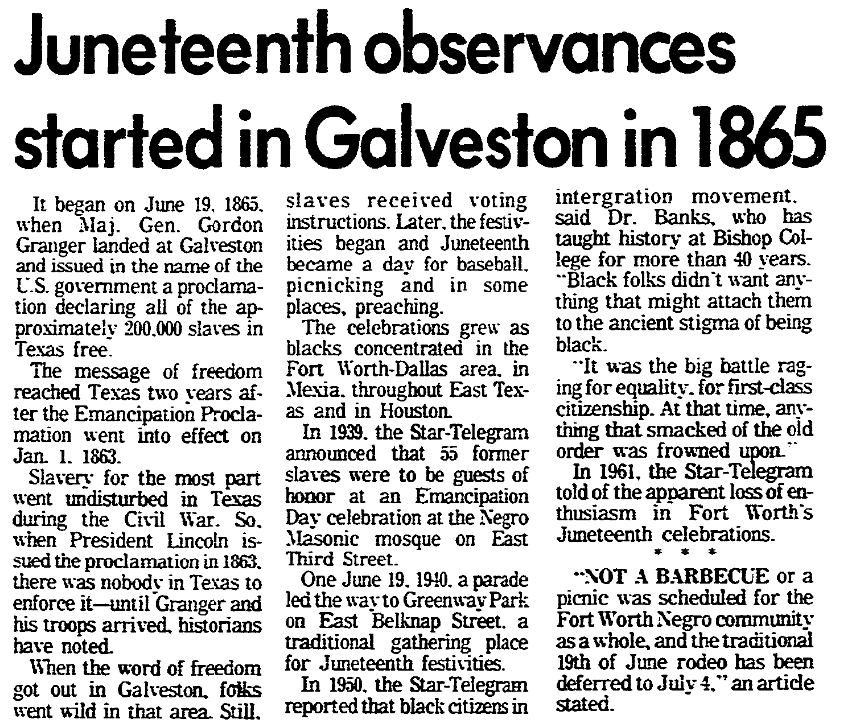

Here is a transcription of this article:

Juneteenth Observances Started in Galveston in 1865

It began on June 19, 1865, when Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger landed at Galveston and issued in the name of the U.S. government a proclamation declaring all of the approximately 200,000 slaves in Texas free.

The message of freedom reached Texas two years after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on Jan. 1, 1863.

Slavery for the most part went undisturbed in Texas during the Civil War. So, when President Lincoln issued the proclamation in 1863, there was nobody in Texas to enforce it – until Granger and his troops arrived, historians have noted.

When the word of freedom got out in Galveston, folks went wild in that area. Still, most of the slaves were in East Texas and government troops moved inland to spread the word.

“Now just like up in other states there were some pockets where some (slave) masters maintained strict control even after the amendment abolishing slavery. But on the whole, slavery throughout the state, slavery as an institution, was abolished,” Dr. Melvin Banks of Dallas’ Bishop College said.

The earliest Juneteenth celebrations were occasions for political rallying where the newly freed slaves received voting instructions. Later, the festivities began and Juneteenth became a day for baseball, picnicking and in some places, preaching.

The celebrations grew as blacks concentrated in the Fort Worth-Dallas area, in Mexia, throughout East Texas and in Houston.

In 1939, the Star-Telegram announced that 55 former slaves were to be guests of honor at an Emancipation Day celebration at the Negro Masonic mosque on East Third Street.

On June 19, 1940, a parade led the way to Greenway Park on East Belknap Street, a traditional gathering place for Juneteenth festivities.

In 1950, the Star-Telegram reported that black citizens in Forth Worth flocked to Forest Park and Botanic Garden to celebrate June 19. A group of black ministers complained in 1953 that public parks and amusement facilities were open to blacks only on Juneteenth. The group asked blacks to boycott these festivities.

However, the Star-Telegram reported the next day that more than 1,000 Juneteenth observers visited Forest Park Zoo.

Something began happening to the Juneteenth spirit in the years to come.

“It was the beginning of the integration movement,” said Dr. Banks, who has taught history at Bishop College for more than 40 years. “Black folks didn’t want anything that might attach them to the ancient stigma of being black.

“It was the big battle raging for equality, for first-class citizenship. At that time, anything that smacked of the old order was frowned upon.”

In 1961, the Star-Telegram told of the apparent loss of enthusiasm in Fort Worth’s Juneteenth celebrations.

“Not a barbecue or a picnic was scheduled for the Forth Worth Negro community as a whole, and the traditional 19th of June rodeo has been deferred to July 4,” an article stated.

A spokesman for the black community explained that Negroes “these days” were focusing on the ideal of unity of the races and did not concede any longer that a separate independence day was needed.

It was almost 10 years later that Juneteenth began to reemerge. The new black pride movement rekindled an interest in black history. The black-is-beautiful trend extended to an almost forgotten Juneteenth.

In 1974, the Community Development Fund and several interested citizens formally resurrected the 19th of June for Fort Worth citizens.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Articles:

Interesting data, thanks.

Glad you enjoyed the article, Nick; thanks for commenting.