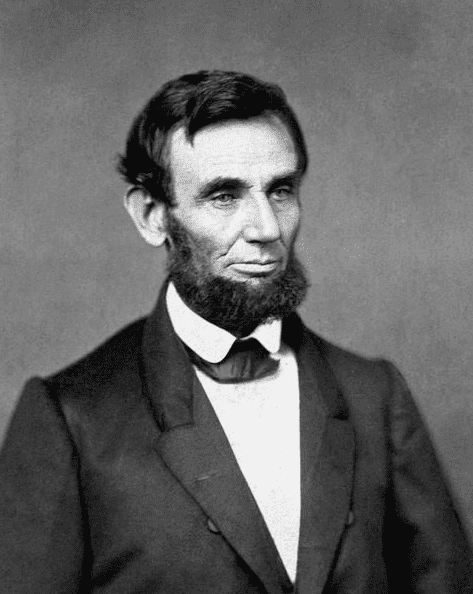

President Abraham Lincoln’s determined objective and steadfast focus in waging the Civil War initially was preserving the Union – not freeing the slaves or forever ending slavery in the United States. He personally regarded slavery as an evil and was convinced it would eventually disappear, but on several occasions stated his belief that a president lacked the constitutional authority to abolish slavery.

However, in the spring and summer of 1862 Lincoln began to change his mind. On 22 September 1862, he issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, due to go into effect in 100 days, declaring that all slaves held in states rebelling against the Union would be free.

The Emancipation Proclamation did not free all slaves – a common misunderstanding of this important act. Believing that only a constitutional amendment could make slavery illegal in the U.S., Lincoln used his powers as commander-in-chief to issue the Emancipation Proclamation as a wartime measure aimed at crippling the enemy’s labor force. His proclamation did not touch slavery in the slave-holding border states that remained loyal to the Union: Delaware, Maryland, Missouri and Kentucky.

There were other parts of the country where slavery remained untouched by the Emancipation Proclamation. New Orleans and most of Tennessee had been recaptured by Union forces, and those areas were exempted from the act, as were 48 counties in Virginia that had declared their loyalty and were in the process of forming the new state of West Virginia. Also, by allowing 100 days before the proclamation would go into effect, Lincoln gave individual members of the Confederate States of America three months to return to the Union and thereby preserve slavery within their borders.

Finally, on 1 January 1863, Lincoln issued his second and final Emancipation Proclamation, naming the ten recalcitrant states that remained in rebellion and formally freeing their slaves: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia.

Lincoln was criticized for not freeing all slaves everywhere. In fact, the irony of the Emancipation Proclamation is that Lincoln only tried to free slaves where the Union had no control – and, depending on one’s perspective – no legal authority, while leaving slavery untouched where the Union had control and unquestioned legal authority.

As his own Secretary of State, William H. Seward, wryly noted: “We show our sympathy with slavery by emancipating slaves where we cannot reach them and holding them in bondage where we can set them free.”

In understanding the limitations of the Emancipation Proclamation, it is helpful to remember that Lincoln’s main objective was preserving the Union. He did not want to overstep his constitutional authority or enrage anyone in the slave-holding border states – or Northerners who supported slavery – by freeing all slaves.

Lincoln had written his proclamation over the summer of 1862 and was determined to announce it. However, the war in Virginia had been going badly for the Union that summer, highlighted by the defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run (Manassas), and Lincoln feared that issuing a decree freeing the slaves would be seen as a desperate act to avoid defeat rather than a courageous and morally right action.

He anxiously awaited a Union victory, and finally got what he wanted at the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) on 17 September 1862. Although technically a draw, with the Union actually suffering over 2,000 more casualties than the Confederacy, the North – and especially beleaguered Union General George B. McClellan – claimed that Antietam was a great Union victory. Five days later, Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

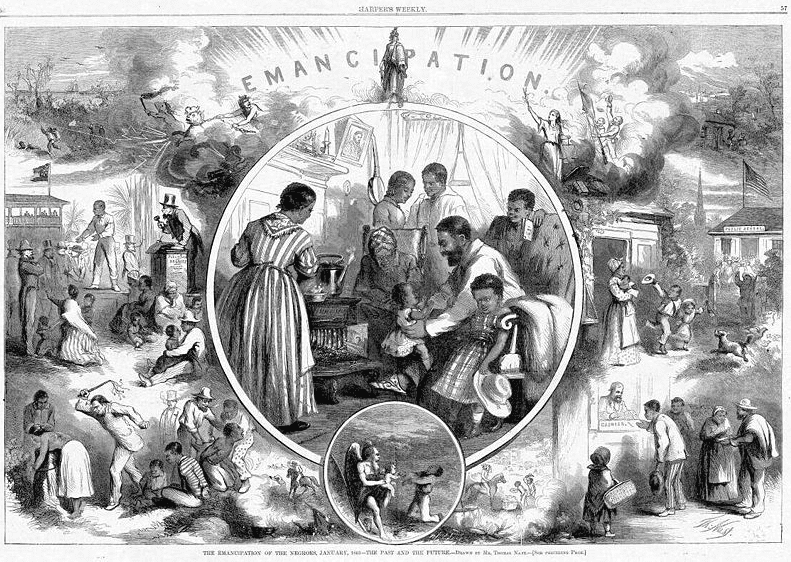

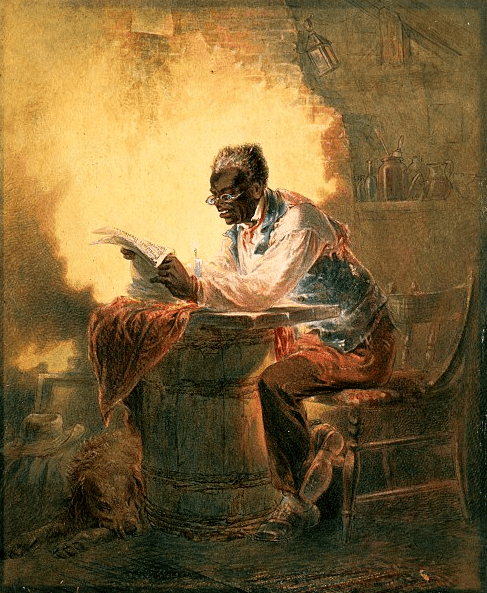

Along with beginning the process of freeing some four million slaves, the Emancipation Proclamation added a moral crusade to the Union’s wartime goals – the rallying cry became “Preservation and Liberty!” The proclamation also effectively ended any chance that Great Britain and France, two nations that had already abolished slavery, would formally recognize the Confederate States of America.

After President Lincoln was assassinated and the Civil War ended, some abolitionists feared the Emancipation Proclamation would only be a temporary measure designed to end the war, and that slavery would be resurrected once peace was established. Their fears were put to rest when, on 18 December 1865, the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution made slavery illegal.

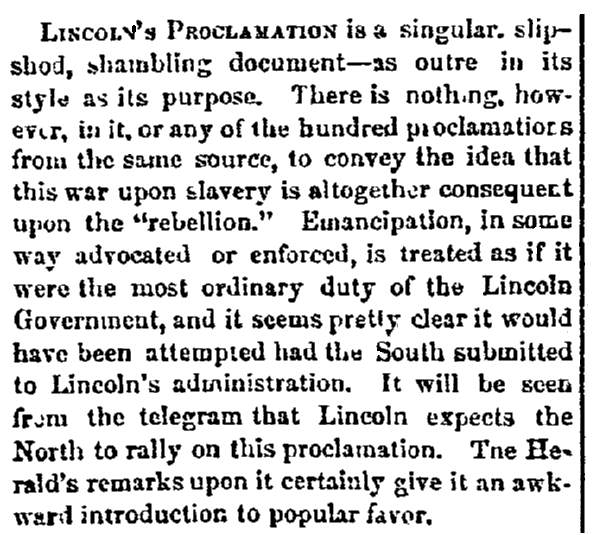

The first three of the following four newspaper articles show Southern reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation. The fourth, from a Northern newspaper, gives the full text of the proclamation to its readers.

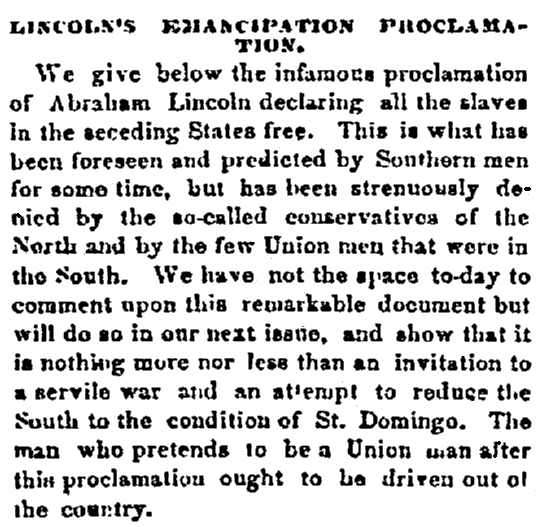

Here is a transcription of this article:

LINCOLN’S PROCLAMATION is a singular, slipshod, shambling document – as outré in its style as its purpose. There is nothing, however, in it, or any of the hundred proclamations from the same source, to convey the idea that this war upon slavery is altogether consequent upon the “rebellion.” Emancipation, in some way advocated or enforced, is treated as it if were the most ordinary duty of the Lincoln Government, and it seems pretty clear it would have been attempted had the South submitted to Lincoln’s administration. It will be seen from the telegram that Lincoln expects the North to rally on this proclamation. The Herald’s remarks upon it certainly give it an awkward introduction to popular favor.

Here is a transcription of this article:

LINCOLN’S EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION.

We give below the infamous proclamation of Abraham Lincoln declaring all the slaves in the seceding States free. This is what has been foreseen and predicted by Southern men for some time, but has been strenuously denied by the so-called conservatives of the North and by the few Union men that were in the South. We have not the space to-day to comment upon this remarkable document but will do so in our next issue, and show that it is nothing more nor less than an invitation to a servile war and an attempt to reduce the South to the condition of St. Domingo. The man who pretends to be a Union man after this proclamation ought to be driven out of the country.

True to its word, the Chattanooga Daily Rebel followed up with longer and stronger comments in its next issue, likening Lincoln’s action to the bloody raid John Brown made on Harper’s Ferry in the hopes of starting a slave rebellion.

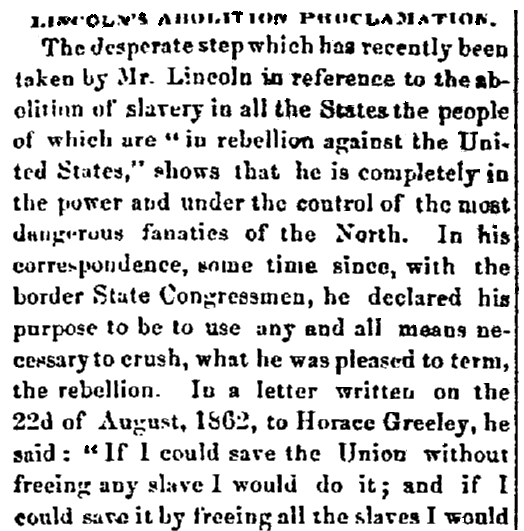

Here is a partial transcription of this article:

LINCOLN’S ABOLITION PROCLAMATION.

The desperate step which has recently been taken by Mr. Lincoln in reference to the abolition of slavery in all the States the people of which are “in rebellion against the United States,” shows that he is completely in the power and under the control of the most dangerous fanatics of the North. In his correspondence, some time since, with the border State Congressmen, he declared his purpose to be to use any and all means necessary to crush, what he was pleased to term, the rebellion. In a letter written on the 22d of August, 1862, to Horace Greeley, he said: “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would do that.” He here assumes a right to do that which no monarch in Europe would dare to attempt, and that is to deprive the people of their property without any law and without any compensation. Instead of talking as a constitutional President he assumes the powers of a dictator. This, though, was merely a declaration of what he would do, and no one would scarcely think that even he would attempt to carry out so nefarious a policy as that now indicated in his proclamation of the 22d of September.

…This is nothing more nor less than an effort to encourage a servile war in the South. Mr. Lincoln having despaired of conquering the South by the overwhelming numbers and power of the North, has at last resorted to the desperate expedient of trying to inaugurate a war between the white and black races of the South, which, if he were successful, would surely terminate in the destruction of the blacks if not of their masters also. A more truly diabolical scheme has never been attempted by any man on so large a scale. It is nothing more nor less than an imitation of the John Brown raid into Virginia, and Abraham Lincoln, by this proclamation, has shown himself a worse man than John Brown in proportion as his position is higher than John Brown’s and his responsibilities greater. This is no new scheme of Mr. Lincoln. It has been maturely considered and long contemplated as the last desperate resort of desperate, wicked and unprincipled men.

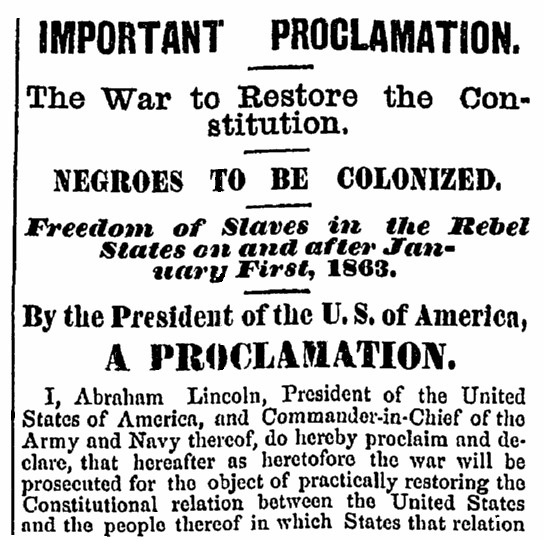

Here is a transcription of this article:

IMPORTANT PROCLAMATION

The War to Restore the Constitution.

NEGROES TO BE COLONIZED.

Freedom of Slaves in the Rebel States on and after January First, 1863.

By the President of the U.S. of America,

A PROCLAMATION.

I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States of America, and Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy thereof, do hereby proclaim and declare, that hereafter as heretofore the war will be prosecuted for the object of practically restoring the Constitutional relation between the United States and the people thereof in which States that relation is or may be suspended or disturbed.

That it is my purpose upon the next meeting of Congress to again recommend the adoption of a practical measure tendering pecuniary aid to the free acceptance or rejection of all the Slave States so-called; the people whereof may not then be in rebellion against the United States, and which States may then have voluntarily adopted, or may thereafter voluntarily adopt, the immediate or gradual abolishment of slavery within their respective limits, and that the effort to colonize persons of African descent, with their consent, upon the continent, or elsewhere, with the previously obtained consent of the government existing there, will be continued.

That on the first day of January, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State, or any designated part of a State, the people thereof shall be in rebellion against the Government of the United States, shall be then, thenceforward and forever free, and the Executive Government of the United States, the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such or any of them in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

That the Executive will on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof respectively shall then be in rebellion against the United States, and the fact that any States or the people thereof, shall on that day be in good faith represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, [shall,] in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such States and the people thereof [are not then] in rebellion against the United States. That attention is hereby called to an act of Congress entitled “An Act to Make an Additional Act of War,” approved March 13th, 1862.

(The section referred to forbids anyone in the army or navy returning [a] fugitive [slave], under penalty of a dismissal from service.)

Also the 9th and 10th sections of an act entitled “An Act to Suppress Insurrection, to Punish Treason and Rebellion, to Seize and Confiscate Property of Rebels, and for Other Purposes.” Approved, July 17th, 1862. And which sections are in the words and figures following:

(These sections are a part of the Confiscation Act, declaring the slaves of all rebels free, &c., &c.)

And I do hereby enjoin upon and order all persons engaged in the military and naval service of the U.S. to observe, obey, and enforce, within their respective spheres of service above recited, and the Executive will in due time recommend that all citizens of the U.S. who shall have remained loyal thereto throughout the rebellion, shall, upon the restoration of the Constitutional relation between the U.S. and their respective States and people, if their relations shall have been suspended or disturbed, be compensated for all loss by acts of the U.S., including the loss of slaves.

In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Seal of the U.S. to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this 22d day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, and of the independence of the U.S. the eighty-seventh.

[Signed] Abraham Lincoln

By the President.

[Signed] Wm. H. Seward

Sec. of State.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Articles: