It took three tries, but on 21 March 1965 several thousand demonstrators led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., began a Voting Rights March from Selma to Montgomery that succeeded in reaching the Alabama state capital. Their first march had ended in violence when state and local police attacked the 600 peaceful marchers on March 7 in Selma, injuring dozens and sending 17 to the hospital, a day of infamy known as “Bloody Sunday.” Television networks interrupted their normally-scheduled programming to show Americans the upsetting images of police brutality, and these pictures were broadcast and printed around the world.

Two days later, Dr. King – who had missed the first march – led a second attempt. Like the original march, they were protesting the police slaying of civil rights worker Jimmie Lee Jackson on February 18, as well as the hostile conditions in Selma and the surrounding area that denied African Americans their constitutional right to vote. Adding fuel to their passion was the violence they had suffered on Bloody Sunday. However, as soon as the demonstrators crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge (where they had been beaten two days earlier), Dr. King turned the marchers back; they decided to wait until a court order was issued granting them the right to protest without police interference.

After receiving that court order, the third march began on March 21 protected by thousands of U.S. Army soldiers, members of the Alabama National Guard, Federal Marshals, and agents from the FBI. After five days the demonstrators reached Montgomery, over 50 miles away. More than 25,000 supporters marched the last leg of the trip together, and listened intently as Dr. King gave his emotional “How Long, Not Long” speech on the steps of the State Capitol Building.

Their protest was a success. After Bloody Sunday the nation – and the whole world – was watching. On March 15 President Lyndon Johnson made an important speech to Congress introducing voting rights legislation, and on 6 August 1965 he signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

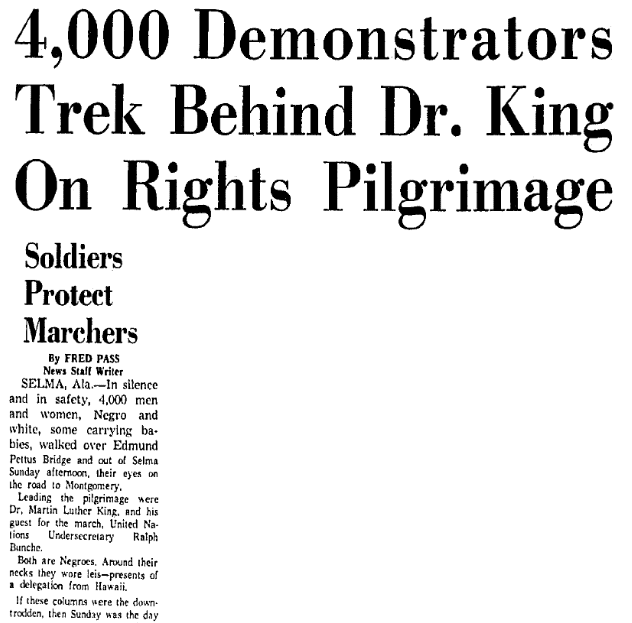

The beginning of the third and successful Selma to Montgomery Voting March was reported on the front page of this Texas newspaper.

Here is a transcript of this article:

4,000 Demonstrators Trek behind Dr. King on Rights Pilgrimage

Soldiers Protect Marchers

By Fred Pass, News Staff Writer

Selma, Ala.—In silence and in safety, 4,000 men and women, Negro and white, some carrying babies, walked over Edmund Pettus Bridge and out of Selma Sunday afternoon, their eyes on the road to Montgomery.

Leading the pilgrimage were Dr. Martin Luther King and his guest for the march, United Nations Undersecretary Ralph Bunche.

Both are Negroes. Around their necks they wore leis—presents of a delegation from Hawaii.

If these columns were the downtrodden, then Sunday was the day for them to lift their heads.

Their way had been opened by federal court order. And the military might of the United States stood by to protect them.

At the foot of the bridge where state troopers with clubs and gas had halted them two weeks before, military police of the 720th Battalion from Ft. Hood stood on guard to let them pass.

Overhead, three helicopters encircled them, each carrying observers to watch for trouble. Assistant Atty. Gen. Ramsey Clark cruised the march route.

Federalized National Guardsmen, ordered in by President Johnson, guarded the route of the first day’s march. Bayonets fixed but sheathed, they stood by the road and shuttled along the line in Jeeps.

But there was no trouble. A sizable crowd of citizens parked their cars beside the 4-lane stretch of Highway 80 beyond the bridge and watched. They remained almost as silent as the marchers. There was some heckling.

Teenagers rode on side streets in a car painted, “Welcome to Selma, Peace and Quiet.”

The Negroes and their white sympathizers, many of them clergymen, marched to protest discriminatory practices in Alabama voting registrations and other grievances. But it was more. One of their leaders said this was not a show, but a war against the social structure of America.

At Brown’s Chapel, where demonstrators have been launching various kinds of demonstrations in Selma for more than two months now, Dr. King spoke at a service prior to the march which began a half hour past noon.

“We are standing up together to make it clear we intend to see that brotherhood of man is a reality,” he said.

King praised President Johnson’s speech to the Congress last week in calling for voting rights legislation.

“Never before has a President of the United States spoken more eloquently or more unequivocally on civil rights,” King declared.

He said that Negroes, smothered in poverty and taught in segregated and inferior schools, have little money and not much education, but he added:

“Thank God we have bodies and feet. We’ve waited a long time for freedom. Now is the time.”

Then the marchers formed in Selma’s Sylvan Street, eight abreast. Near the head was placed an old Negro man, Cager Lee, the grandfather of Jimmy Jackson, who was shot by a state trooper at Marion, Ala., several weeks ago and later died.

Only minutes before the sun set, the column of people reached their first campsite, 7.3 miles from where they started. There still remains 43 miles and four days to go before they reach Montgomery, the State Capitol, and perhaps Gov. George C. Wallace.

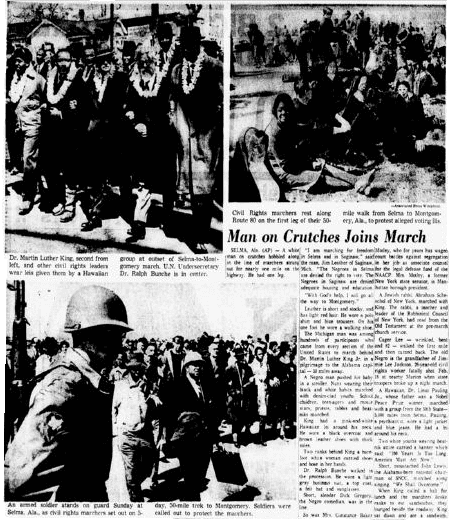

Some more details about the march appeared in the same issue of that Texas newspaper.

Here is a transcript of this article:

Man on Crutches Joins March

Selma, Ala. (AP)—A white man on crutches hobbled along in the line of marchers strung out for nearly one mile on the highway. He had one leg.

“I am marching for freedom in Selma and in Saginaw,” said the man, Jim Leather of Saginaw, Mich. “The Negroes in Selma are denied the right to vote. The Negroes in Saginaw are denied adequate housing and education.

“With God’s help, I will go all the way to Montgomery.”

Leather is short and stocky, and has light red hair. He wore a polo shirt and blue trousers. On his one foot he wore a walking shoe.

The Michigan man was among hundreds of participants who came from every section of the United States to march behind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in a pilgrimage to the Alabama capital—50 miles away.

A Negro man pushed his baby in a stroller. Nuns wearing their black and white habits marched with denim-clad youths. Schoolchildren, teenagers and movie stars, priests, rabbis and beatniks marched.

King had a pink-and-white Hawaiian lei around his neck. He wore a black overcoat and brown leather shoes with thick soles.

Two ranks behind King a barefoot white woman carried shoes and hose in her hands.

Dr. Ralph Bunche walked in the procession. He wore a light gray business suit, a top coat, a felt hat and sunglasses.

Short, slender Dick Gregory, the Negro comedian, was in the line.

So was Mrs. Constance Baker Motley, who for years has waged court battles against segregation in her job as associate counsel for the legal defense fund of the NAACP. Mrs. Motley, a former New York state senator, is Manhattan borough president.

A Jewish rabbi, Abraham Scheschel of New York, marched with King. The rabbi, a teacher and leader of the Rabbinical Council of New York, had read from the Old Testament at the pre-march church service.

Cager Lee—wrinkled, bent and 82—walked the first mile and then turned back. The old Negro is the grandfather of Jimmie Lee Jackson, 26-year-old civil rights worker fatally shot Feb. 18 at nearby Marion when state troopers broke up a night march.

A Hawaiian, Dr. Linus Pauling Jr., whose father was a Nobel Peace Prize winner, marched with a group from the 50th State—5,000 miles from Selma. Pauling, a psychiatrist, wore a light jacket and blue jeans. He had a lei around his neck.

Two white youths wearing beatnik attire carried a banner which said: “100 Years Is Too Long. America Must Act Now.”

Short, moustached John Lewis, the Alabama-born national chairman of SNCC, marched along singing “We Shall Overcome.”

When King called a halt for lunch and the marchers broke ranks to eat sandwiches, they lounged beside the roadway. King sat down and ate a sandwich.

Related Articles:

Loved these articles. I was very young at this time, and from the West not really knowing what was going on at the time.

Thanks for writing us, Debra. We’ll try to keep more articles coming that will interest you!