The 10,000 people living in and around Nome, Alaska, were in desperate straits in January 1925. It was the dead of winter, howling winds, snow and ice, with bitterly cold temperatures, had cut their area off from the outside world – and there was a killer in their midst.

An epidemic of diphtheria had broken out, which was especially fatal to little children and the Native population, and the one and only doctor in Nome did not have any active diphtheria antitoxin to combat the disease. Somebody, somehow, had to rush medicine to Nome, or thousands of people would die.

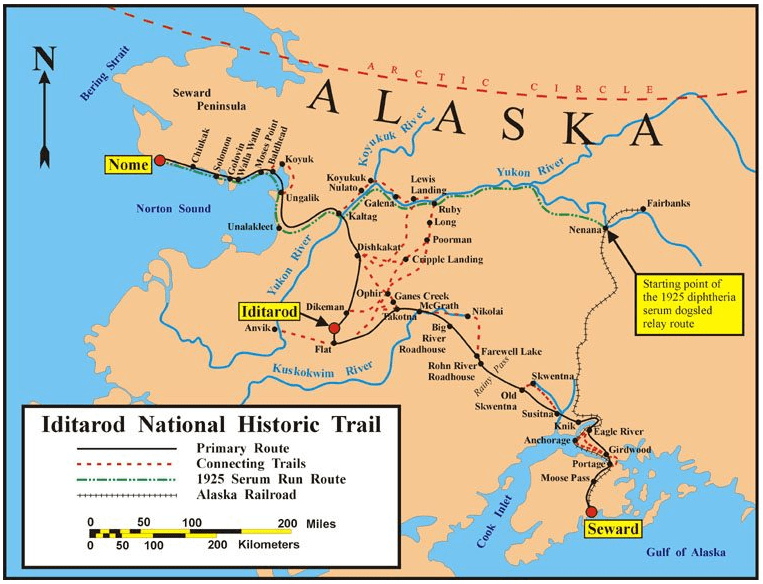

There were no experienced pilots or working planes in Alaska that winter – and with the storms, darkness and extreme subzero temperatures, a flight would have almost no chance of success anyway. There was only one answer, and 20 mushers and 150 sled dogs banded together to meet the challenge: carry a batch of the life-saving diphtheria antitoxin from Nenana, in the interior of Alaska Territory, all the way to Nome – 674 miles of raw wilderness in the most extreme conditions imaginable.

And they did it, in an amazing 127½ hours, a little over 5 days! (Normally the dog sled run from Nenana to Nome, used to carry mail and supplies, took 25 days.) The precious medicine arrived in Nome on Feb. 2.

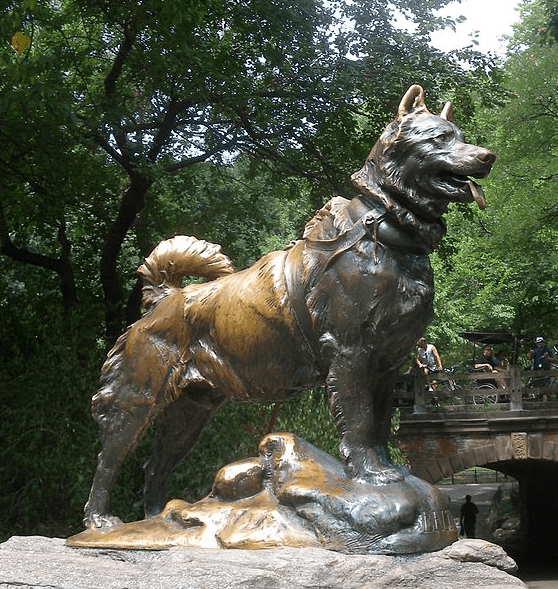

Setting up relays like a Pony Express team, each musher and dog sled team carried the antitoxin part of the way and then handed it over to the next team. They had to cross mountains, frozen rivers and the treacherous ice of Norton Sound. Temperatures hovered near minus 40 degrees and got as cold as 60 degrees below zero! On the last leg of the relay Gunnar Kaasen and his nearly-frozen dogs plunged into the teeth of a blizzard, with 80 mile-an-hour winds whipping up the snow so fiercely that Kaasen could not see the dogs harnessed closest to his sled. He had to rely on his lead dog, Balto, to get them through.

They made it, and the delivery of 300,000 units of the antitoxin, although frozen upon delivery, proved effective in stemming the epidemic until more medicine was brought in later to completely turn the tide against the disease. There is no telling how many lives those brave 20 men and their heroic 150 dogs saved, but they received a nation’s heartfelt thanks.

This epic race against time and harsh conditions to save lives cut off from the rest of the world captured the public’s imagination. Newspapers and radio broadcasts closely followed the progress of the relays. The following two newspaper articles are good examples of the attention the rescue operation received.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Last Relay Driver Arrives at Nome with Serum

Kasson Fights Blizzard on Final Lap with Precious Antitoxin

Six Hundred and Fifty Mile Mush across Arctic Wastes to Save Diphtheria Sufferers Made in 127½ Hours

By Associated Press.

NOME, Alaska, Tuesday, Feb. 3. – Exhausted from two days’ loss of sleep and driving a team of dogs sixty miles through a blinding blizzard for seven and one-half hours in order to deliver 300,000 units of diphtheria antitoxin to this town yesterday, Gunnar Kasson [i.e., Kaasen] was still sleeping early today. He was the last relay driver in the 650-mile dash from Nenana.

A portion of the serum, frozen on its arrival, was thawed out yesterday afternoon and used on patients. Dr. Curtis Welch, government physician, said he could not tell if the antitoxin had deteriorated until the effects were noted. One new diphtheria case was reported yesterday, Mrs. John Winthers being stricken.

Kasson accomplished a feat seldom attained by seasoned mushers of the sub-Arctic. For two days he waited on the trail at Bluff with thirteen dogs, headed by Balto, sagacious canine leader, of the Hammon Consolidated Gold Fields Company, to transfer serum shipped from Anchorage via Nenana, from Olsen’s relay team.

Leonard Seppalla, undefeated musher of the North, met a relay team at Shaktolik, east of Norton Sound, and carried the antitoxin to Golofnin, on the north shore of Norton Sound, Bering Sea, where Olsen awaited him.

Rohn Reaches Nome

Despite a temperature of 28 degrees below zero and fanned by a stiff wind, Kasson mushed on. The storm and darkness prevented him from meeting Fred Rohn, who waited at Solomon to make the last short relay dash into Nome. He [Kaasen] kept up the pace, however, and reached here at daybreak. Four dogs in his team were badly frozen.

Rohn arrived before noon from Solomon after he learned Kasson had missed him. No word has been received from Seppalla. The former Finnish athlete is expected to return slowly, resting at villages to feed his tired dogs.

The blizzard yesterday stopped operation of a telephone line on the route taken by the antitoxin and linking Safety, twenty-one miles from Nome, with Solomon, thirty-three miles from Nome. Before communication ceased word had been forwarded, at the [insistence] of Doctor Welch, that the dog teams should not proceed until the storm was allayed, but that the serum should be taken into a roadhouse and kept warm.

During the night, Fred Rohn, one of those waiting with dogs, sent word here from Safety that the wind was blowing eighty miles an hour, whirling the snow so that it was impossible for man or beast to face the storm. He said that the ice at Norton Sound in that vicinity, over which the antitoxin was expected to pass, was in constant motion by reason of a heavy ground swell.

One of Greatest Races in History

It was one of the greatest dog team races in the history of Alaska, from Nenana to Nome. The serum was shipped by train on the Alaska Railroad from Anchorage to Nenana. William Shannon drove the first relay out of Nenana.

The 650-mile trip by relay dog teams over the frozen ice of the Tanana and Yukon Rivers and around Norton Sound was made in 127½ hours, considered by mushers to be a world’s record. A record of 78 hours, 44 minutes and 57 seconds, minus 20 hours and 17 minutes for rest, was made in a 408-mile return derby from Nome to Candle.

Seppalla, undefeated musher of the North and former Finnish athlete, met the antitoxin relay team from Unalaklik at Shaktolik, east of Norton Sound, halfway between the foothills and Bonanza roadhouse. After making forty miles, he turned around and retraced his steps seventy miles to Chinik, sometimes called Golofin, a village on the north shore of Norton Sound, Bering Sea, where he turned over the shipment to Olsen, another relay driver.

Olsen continued to Bluff, sixty miles east of here, where Kasson had awaited the arrival of the serum for two days without sleep.

During the harnessing of Kasson’s team the antitoxin was taken indoors and warmed up. When the team was ready, Kasson cracked the whip and the dogs sped toward Nome.

Praise for Leader

Kasson, who fought through a severe blizzard, gave the entire credit to Balto, the leader of his dog team. He said the last leg of the relay would have been unsuccessful if Balto had not been on the team. Balto was named after a well known early character in this section, the late Lapp Baltow.

Here is a transcription of this article:

GALLANT RACE

Fleet Dogs and Intrepid Drivers Bring Medical Supplies to Nome

The country has been thrilled by the dog team race from the interior of Alaska to the coast at Nome, where medical supplies were sorely needed to combat an epidemic of diphtheria. The race was a contest against time and the stake was the lives of little children. The errand of mercy enlisted some of the finest athletes in the Northland and teams of the swiftest dogs. Blizzards and subzero temperatures did not daunt the gallant drivers or the stout dog teams. The call of a neighbor in distress was answered in the whole-hearted way characteristic of the North.

The epidemic at Nome could be easily handled with ample medical supplies, but the isolated position of the town and the difficulties of transportation add immeasurably to the dangers. And the distressing feature of the situation is that the little children are the greatest sufferers. Without the aid of antitoxin, reliance had to be placed on nursing and quarantine measures to check the spread of the ailment.

It was a little more than twenty years ago that diphtheria was regarded as a scourge of childhood. The whole country was in the predicament in which Nome now finds itself today. Then came the discovery of diphtheria antitoxin and the death rate dropped from an appalling ratio to almost nothing. It is only when a community finds itself without the weapons supplied by science that there is danger that an epidemic may get beyond control. Oddly enough, adults possess a certain measure of immunity from the disease. The chief sufferers are children of tender years.

The news that the precious package containing a pitifully small quantity of the antitoxin had arrived at Nome was received with joy here. The satisfaction which came from a knowledge that the long race had been successful was lessened somewhat by the information that supplies had been frozen. However, in the opinion of laboratory experts the remedy has not been damaged by the freezing. In any event it will not be long before other means are found to give Nome the help it needs. The danger to little children rouses the protective impulse of every parent in the country.

Related Article: