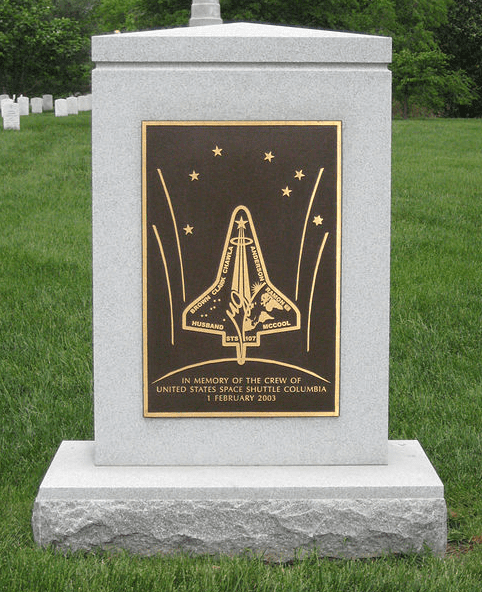

On 1 February 2003, almost exactly 17 years after the space shuttle Challenger blew up, the nation and its space program received another jolting setback when the shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon reentering the atmosphere, killing all seven members of its crew. Just as the nation – especially the students of teacher Christa McAuliffe – was stricken with grief at the Challenger disaster, the loss of the Columbia plunged the country into mourning once again.

A series of successes after the loss of the Challenger had made shuttle flights seem almost routine. The Columbia was the nation’s first space shuttle, its initial flight occurring on 12 April 1981, and it had safely completed 27 missions in its long useful career.

However, when it lifted off on January 16 for what turned out to be its final mission, a piece of insulating foam from a fuel tank fell off and struck one of Columbia’s wings, making a small hole. When the shuttle reentered the Earth’s atmosphere 16 days later, hot gases entered through the hole causing the shuttle to break apart.

In the wake of the Columbia disaster, many people questioned the rationale for continuing a costly and apparently dangerous space program. One answer came in the form of this editorial published by the Augusta Chronicle.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Our Debt to Columbia

If video had been available for centuries rather than only decades, humanity would have recorded too many nightmarish sights to remember.

But in the scheme of things, the technology is still fresh. And so are the horrific images being filed away for painful posterity: the Kennedy assassination, the Challenger explosion, the Sept. 11 attacks. The list is growing.

We just added one for the ages on Saturday.

None of us who stumbled onto the news Saturday morning, or were told by a friend to tune in, will ever forget the soul-piercing sight of the space shuttle Columbia streaking across the big blue Texas sky – and into fiery nothingness.

It’s amazing, isn’t it, that we can have instant worldwide communication networks – but at times such as these, it’s difficult for us to get our heads and hearts to communicate. We watched those images and, in our minds, knew full well that the seven brave souls on board could not possibly have survived. But somehow, our hearts weren’t listening for the longest time. We had to hear President Bush say it out loud.

“The Columbia is lost,” he said, hours after we should have known it. “There are no survivors.”

Except, of course, for a grieving nation.

Making the day more difficult was the fear that every such disaster brings today: When the shuttle Challenger exploded in a fireball in 1986, we at least had the small comfort, even without knowing it, of assuming it was a horrible accident; today, before the smoke even clears, we have to first rule out terrorism.

While that seems to have been done in this case, given that the Columbia was at 207,135 feet when it disintegrated, it is but small comfort. It is still a national tragedy. Seven heroic lives were lost, and millions more were diminished.

And let’s face it: Our mourning is compounded by more than a little guilt over having taken the space program for granted in recent years. How many of us knew a shuttle was even in the air Saturday? How many of us watched the launch on Jan. 16 and counted the days since? How many of the crew had become household names?

We promised! We promised ourselves we wouldn’t ever do that again, not after Challenger. But while our astronauts sometimes seem superhuman, the rest of us are not; it’s impossible to see repeated shuttle launches and landings over the years and not be lulled into complacency.

In many ways, that’s partly the fault of a space agency that has done such a superb job. The professionals at NASA made riding into the hostile environment of space attached to explosive rockets appear routine.

Yet, not even this awful moment will stop our relentless ascent into the heavens. President Bush was quick to make that clear.

“Mankind is led into the darkness beyond our world by the inspiration of discovery and the longing to understand,” he told the country. “Our journey into space will go on.”

People will ask why, of course. They’ll question the wisdom of the shuttle missions. They’ll trot out the requisite “we’ve got enough problems here at home” argument. And not long after the loud boom of the Columbia disaster Saturday, you could almost hear the whir of the congressional investigation engines.

Much of the questioning – indeed, most of it – will be both necessary and constructive. We need to find out what went wrong. We need to examine whether the shuttle technology is up to 21st-century standards. We need to consider all the alternatives and, as one observer said Saturday, “get decisive about what we want to do in space.”

But as for the question of why – why we venture into space – there’s a good reason: because it’s there. And we’re here. And going from here to there is what we do. It’s what the human race is driven to. And if gut-wrenching tragedy or horrifying images had the least little possibility of stopping us, we never would’ve made it this far.

We owe it to the seven heroes of Columbia to keep going.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. The same is true of more recent news. What are your memories of the Columbia disaster?

Related Articles: