The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), founded in 1958, has been America’s leading government agency for space exploration and scientific and aeronautics research for 57 years. The highlight of NASA’s history occurred on 20 July 1969 when the Apollo 11 space flight successfully landed the first humans on the moon.

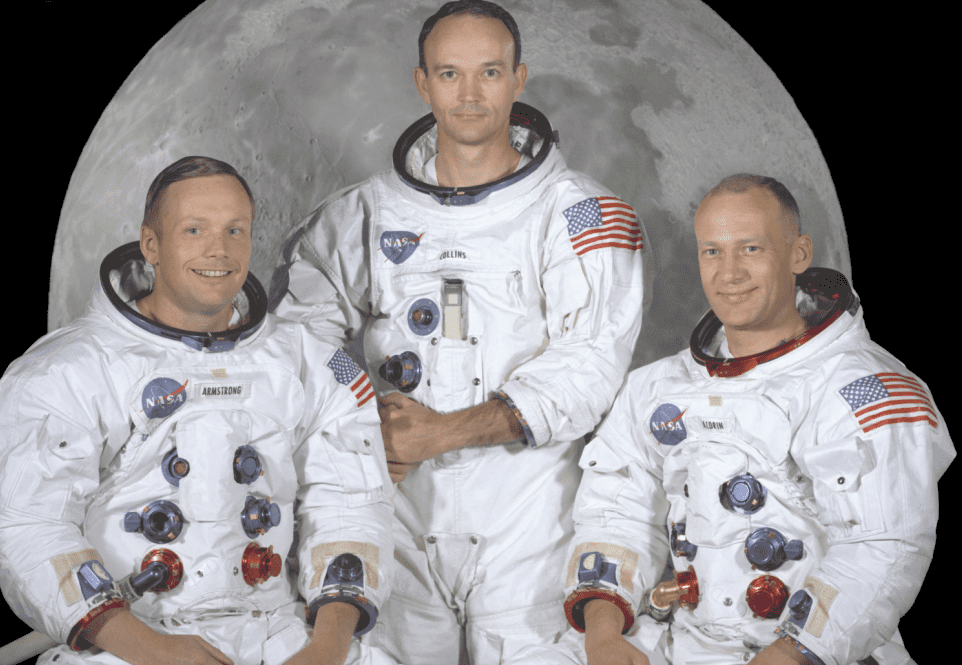

Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin thrilled Americans and the world with their two-hour walk on the moon’s surface while astronaut Michael Collins piloted the command module orbiting above the lunar explorers.

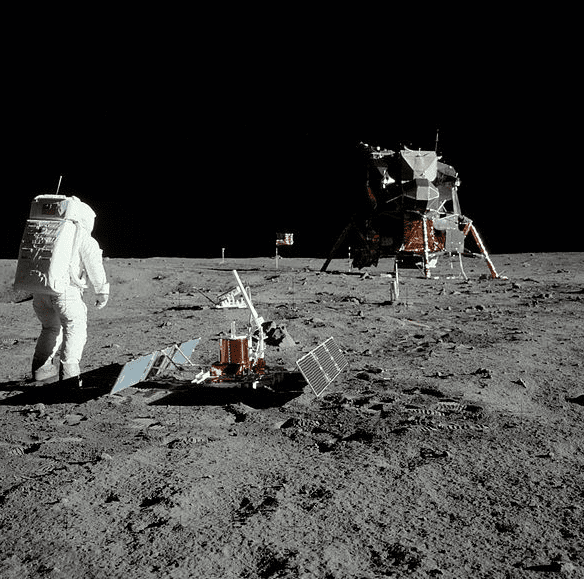

The Apollo 11 mission left an American flag, a plaque, several scientific instruments, and some abandoned equipment on the moon’s surface, and brought back scientific data and 47.5 pounds of rocks. The successful mission also created a proud legacy for the NASA space agency. However, in today’s difficult economic conditions some people are doubting NASA’s value, feeling the agency is bloated, expensive, and purposeless. The significance of what Apollo 11 accomplished eludes much of the American public today.

Many people seem to have lost the sense of wonder, even awe, that gripped America – and the whole world – when Armstrong and Aldrin stepped on the surface of the moon 46 years ago today. For many observers at the time, however, it seemed like the greatest achievement in the history of humankind, a breakthrough proving the limitless capacity of human imagination and ingenuity. That feeling of euphoria and amazement comes across clearly in the following newspaper article.

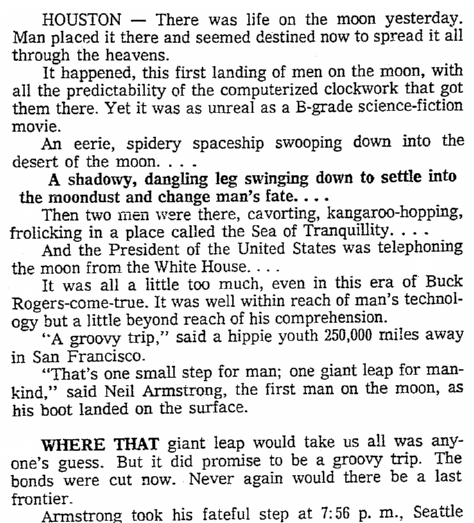

The Seattle Daily Times’s lead story gave the riveting details of the moon landing:

Man Walks on Moon

U.S. Astronauts Open New Era

By William W. Prochnau, Times Staff Reporter

Houston—There was life on the moon yesterday. Man placed it there and seemed destined now to spread it all through the heavens.

It happened, this first landing of men on the moon, with all the predictability of the computerized clockwork that got them there. Yet it was as unreal as a B-grade science-fiction movie.

An eerie, spidery spaceship swooping down into the desert of the moon…

A shadowy, dangling leg swinging down to settle into the moondust and change man’s fate…

Then two men were there, cavorting, kangaroo-hopping, frolicking in a place called the Sea of Tranquility…

And the President of the United States was telephoning the moon from the White House…

It was all a little too much, even in this era of Buck Rogers-come-true. It was well within reach of man’s technology but a little beyond reach of his comprehension.

“A groovy trip,” said a hippie youth 250,000 miles away in San Francisco.

“That’s one small step for [a] man; one giant leap for mankind,” said Neil Armstrong, the first man on the moon, as his boot landed on the surface.

Where that giant leap would take us all was anyone’s guess. But it did promise to be a groovy trip. The bonds were cut now. Never again would there be a last frontier.

Armstrong took his fateful step at 7:56 p.m., Seattle time. It came more than three hours ahead of schedule and after a crater-hopping ride down to the Sea of Tranquility in the spaceship Eagle.

He was joined on the surface of the moon 18 minutes later by his fellow astronaut, Edwin (Buzz) Aldrin. Armstrong remained on the surface for 2 hours and 13 minutes, Aldrin about 30 minutes less.

“Now, I want to back up and partially close the hatch,” Aldrin said as he stepped out on Eagle’s ladder down to the moon. “Making sure not to lock it on the way out.”

“A good thought,” Armstrong acknowledged from below.

The two astronauts, tight-lipped and laconic during the quarter-million-mile trip across space, were playful now, exhilarated in the strange buoyancy of the moon’s weak gravity.

They were expected to play it cool, take no chances. Instead, as one grounded astronaut said in Houston, they bounced around the moon “like a couple of Texas jackrabbits.”

It all was watched by millions of earthbound television viewers, just one in the string of fantastic events that took place on July 20, 1969. It was, surely, the oddest of all television shows.

There were those men, grotesque and dome-headed in their spacesuits, darting across the face of the moon. They guessed beforehand that they would be able to walk 10 miles an hour. But they were running, cutting like football fullbacks.

But if the astronauts were playful now, they also got almost all of their work done on the moon. They deployed three key scientific experiments that should record moon quakes, precisely measure the distance to the moon and capture solar rays.

They gathered up around 60 pounds of lunar rock—not all they wanted—and stowed it in their spaceship.

It would be months, maybe years, before scientists would know exactly what they discovered in their barren lunar sea. But their major goal was just to get there—and, of course, get back.

Apollo 11’s mother ship, Columbia, with Mike Collins aboard, spent the historic day in orbit, waiting for the return.

Eagle touched down on the moon at 1:17 yesterday afternoon. The decision to make the moon walk ahead of schedule was made after it was determined that the astronauts were well-rested. The earlier plan had called for them to sleep four hours before leaving their craft.

Outside, the astronauts surveyed the bleak, boulder-strewn moonscape and found it more attractive than they expected.

“It has a stark beauty all its own,” Armstrong said. “It’s like much of the high desert of the United States. It’s different but very pretty out here.”

And Aldrin’s first words on the moon were, “Beautiful, beautiful.” Less well-planned than Armstrong’s well-honed statement for the history books.

The surface of the moon, they observed from inside the spaceship, was white to gray, chalky and almost colorless. But outside, they found more—chocolate sands, a purple stone, crystalline rock formations. The surface was firm but covered with dusty sand that gave way to make footprints and smudged their gloves.

The landing pods of Eagle sank into the soil only two or three inches. Their footprints were just one-eighth inch deep.

The astronauts were fascinated by it all. Armstrong had planned his first historic words carefully and meaningfully. But, with hardly a pause, he felt compelled to go on and describe the strange sights.

“The surface is fine and powdery,” he said. “I can pick it up loosely with my toe. It does adhere in fine layers like powdered charcoal to the sole and sides of my boots. I only go in a small fraction of an inch. Maybe an eighth of an inch. But I can see the footprints of my boots and the treads in the fine sandy particles.”

The men were not particularly surprised by anything they found. But the mobility they had in the one-sixth gravity of the moon was more than expected. Both were 165-pounders on earth, 27-pound gazelles now on the moon.

“You do have to be rather careful to keep track of where your center of mass is,” Aldrin said, sprinting in front of the cameras. “Sometimes it takes about two or three paces to make sure you’ve got your feet underneath you. But about two or three or maybe four easy paces can bring you to a nearly smooth stop.”

And often they were in awe of what they were doing, just as most of the distant earth was, too.

Even before he walked on the surface, Aldrin felt the need to send a message back to earth.

“This is the L. M. pilot,” the astronaut said, “I would like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours and to give thanks in his or her own way.”

Men would try to contemplate it all, of course. There were men, brilliant men here, saying Armstrong’s step was the most significant event since life first crawled out of the seas. Others thought it was groovy.

Then there was President Nixon, calling the moon.

“Neil and Buzz,” he said, “I am talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House.”

The two men stood there at attention in the Sea of Tranquility, distorted moon puppets, strangers from the future, flanking the American Flag they had planted, in front of the plaque that said they had “come in peace for all mankind.”

“Because of what you have done,” the President said, “the heavens have become a part of man’s world.”

And where did all this begin? In Galileo’s child-like toyings with the first telescope? In the fantasies of Jules Verne?

Who could say? But a dream was being fulfilled—and beginning anew—yesterday as the ungainly spaceship Eagle and its two passengers settled down into that lunar sea.

It might well be that the biggest moment in the flight of Apollo 11—and one of the biggest in the history of man—occurred when Armstrong stepped down off that ladder’s final rung.

Man was on the moon, treading on alien soil, one foot in the future.

But in sheer drama no moment was bigger than the instant when the machine of Apollo 11, the spaceship Eagle, set its talons into moonsoil. No one had any serious doubts here that man, the strange and adaptable creature who had devised all these miracles, would have any real trouble walking on the moon. But first he had to get there.

And the trip down, those final few thousand feet, was harrowing indeed. Inside the spaceship alarm lights were flashing their danger signals from overworked computers and Eagle was four miles off course, heading into a boulder-strewn crater.

There was every indication later, in fact, that an unmanned spacecraft might have crashed in the same situation. But it seemed almost fitting that men should take over from their machines on this, of all flights.

So Armstrong, peering down into those threatening lunar boulders just 250 feet below, took control and steered his spaceship beyond to safety.

Armstrong is an inward man, a man who controls himself rigidly and his voice betrayed no emotion as he lowered himself into history.

“…coming down nicely, 200 feet,” the voice crackled across the void.

“…75 feet, everything’s looking good…light’s on…40 feet, kickin’ up some dust…four forward, drifting to the right a little…”

Then: “Contact light?” The voice excited, now, in a jubilant question to Aldrin. “OK, engines stopped?”

These were the first words from the moon, “contact light,” this test pilot’s affirmation that the greatest test of them all had been made and it had worked.

Then the words from Houston: “We copy you down, Eagle.”

“Houston?” came the voice of Armstrong again. “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

“Roger, Tranquility, we copy you on the ground,” Apollo Control said exuberantly. “You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue here. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

“Thank you,” replied Armstrong in a voice that meant thanks for the $22 billion, thanks for the computers, thanks for the Von Brauns, the Goddards, the Keplers, the Galileos. He was their beneficiary now, their emissary, in a way; our emissary, too.

This strange young man, Armstrong, the symbol of the beginning of an era that even the most visionary of men can’t comprehend. He wanted to be made of steel now and he kept the steel in his voice. But the machinery that got him there also gave away his secret.

The sensors pasted to his chest, those wiretaps on his heart, beamed back the truth: at touchdown, at contact light, Armstrong’s heart was jumping at a furious 156 beats a minute, more than twice the normal rate.

But could there be any wonder at that?

Moments later, relaxing now, his heart rate down to 90, Armstrong matter-of-factly described the approach.

Eagle came in, he said, over a “football-field-sized crater with a large number of big boulders and rocks for about one or two crater diameters around it and it required us to fly manually over the rock field to find a reasonably good area.”

If that was a rather understated way of saying that Eagle almost bounced in among the boulders, it is Armstrong’s way.

Moments later Collins, the loneliest astronaut, orbiting in Columbia high over his departed buddies, called down to see how things were going.

“Sounds like it looks a lot better than it did yesterday,” Collins said in a reference to their earlier sightings from orbit. “It looked rough as a cob then.”

“Tell you what, Mike, it really was rough over the target area,” Armstrong radioed back. “It was extremely rough, cratered and large numbers of rocks, probably many larger than five or ten feet in size.”

“Land down, land long,” Collins observed, with good pilot’s advice.

“Well, we did,” Armstrong replied.

Down there—or up there—at last, the astronauts were somewhat lost. They had landed on the edge of their long-chosen landing zone, landing down and landing long by about four miles.

“Those guys who said we wouldn’t be able to tell precisely where we are, are the winners today,” Armstrong told Houston. “We were a little worried about program alarms and things like that in the part of the descent where we would be normally picking out our landing spot.”

The astronauts quickly assured Houston that they were having no trouble with the moon’s one-sixth gravity—a fact they would exhibit convincingly to the world a few hours later, with their bounding and cavorting in the Sea of Tranquility.

Then they peered out their spaceship windows at scenes men never had seen before—of a strange pock-marked plain, a chalky lunar landscape, an earth suspended, half-moon half-earth home, in the sky.

“There are no stars,” Armstrong said, “but out my overhead hatch I’m looking at the earth. It’s big and bright and beautiful.”

They were sitting in a “relatively level plain, cratered with fairly large numbers of craters from the 5 to 30-foot variety and some ridges, small, 20, 30 feet high…”

There was a moon hill, perhaps a mile away, halfway to the curving horizon and “some angular blocks out several hundred feet in front of us that are probably two feet in size and have angular edges.”

Aldrin, the bookish astronaut, looked out at the moonscape and saw a “collection (of rocks) of just about every variety of shapes, angularities, granularities, about every variety of rock you could find.”

A quarter-million miles away, the geologists could hardly wait.

Up above it all, in Columbia, Collins was getting a little antsy, too. He was just about the only interested earth man who couldn’t watch it all. And he kept calling down to Houston, imploring them to improve his radio communications so he could “follow the action.”

On each pass over the landing area, he squinted down in a fruitless attempt to catch a sun-reflected glimpse of Eagle.

The President talked to Armstrong and Aldrin, but he forgot about Collins. Not very political, that.

When Houston radioed congratulations down to the men in the Sea of Tranquility, Collins interjected, “and don’t forget the one in the command module.”

“OK,” Armstrong told him, joshingly, “you just keep that orbiting base up there ready for us.”

He would and it was Collins, three hours before the landing, who had started Armstrong and Aldrin on their way.

The two craft were separated in orbit, just behind the corner of the moon and out of radio contact, when Collins pushed a button that gently nudged Eagle away from Columbia.

When the two craft popped around the moon’s corner, Armstrong reported that “the Eagle has wheels.”

It was an orbit later before Eagle was really diving for the moon. A 30-second engine burn, again on the back side of the moon, propelled the landing craft into an orbit that brought it to less than 50,000 feet above the surface.

Once again, the anxious men back on earth didn’t know how it had worked until the two spacecraft rounded the corner.

The command module cruised out first and Collins broke the silence: “Listen, baby, everything’s going just swimmingly. Beautiful.”

“Roger, we’re waiting for Eagle,” Houston replied.

“He’s coming along.”

And then it was all clear for the final move, 12½ minutes of retro-fire from Eagle’s descent engine.

“Eagle, you are go for power descent,” the voice came up from Houston.

And Eagle was go for history.