Introduction: In this article – to mark the 109th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic – Gena Philibert-Ortega writes about the ship’s two radio operators and the distress calls they sent out that fateful night. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

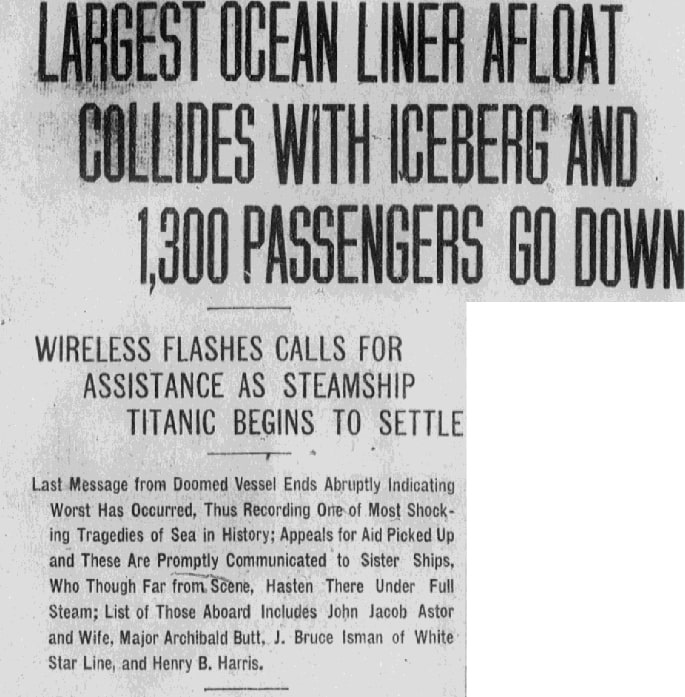

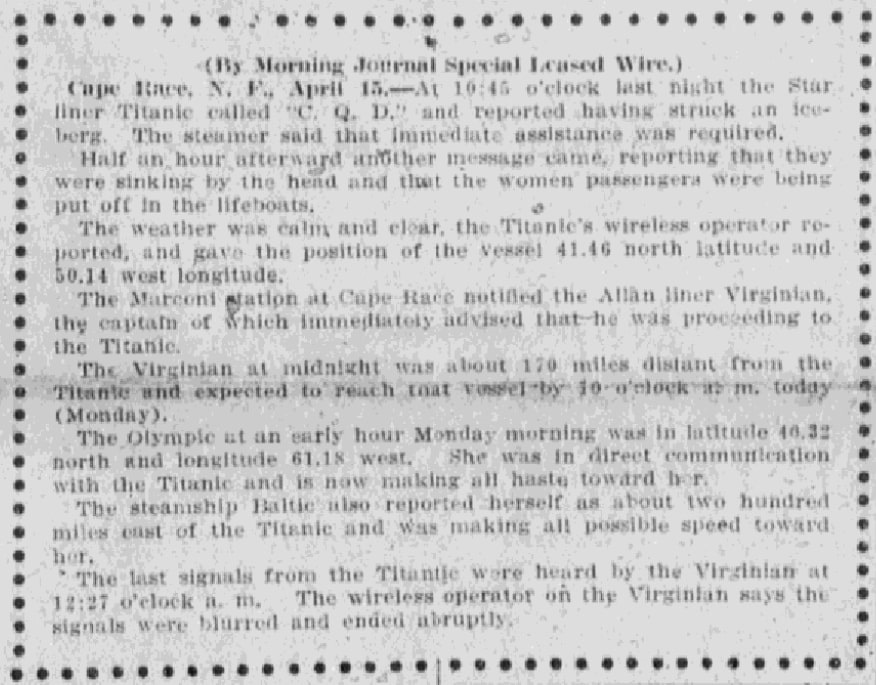

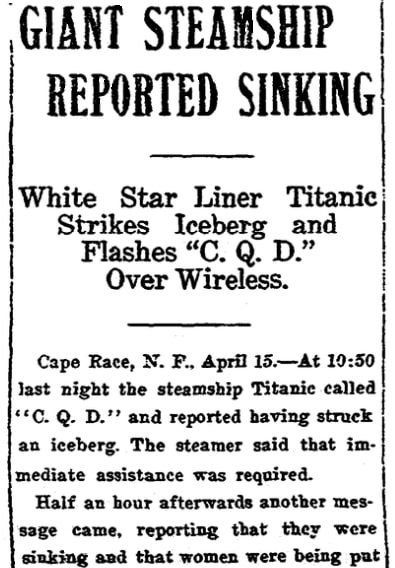

At 11:40 pm on 14 April 1912, RMS Titanic – the largest ship cruising the world’s oceans at that time – hit an iceberg in the North Atlantic during its maiden voyage. Two hours and forty minutes later, at 2:20 am on 15 April 1912, the “unsinkable” passenger ship sank with the loss of more than 1,500 lives. As the disaster was unfolding, the giant cruise ship sent out a series of desperate messages using its state-of-the-art wireless telegraphy equipment.

Monday, 15 April 1912, 12:15 am

CQD CQD CQD CQD CQD CQD MGY Have struck an iceberg. We are badly damaged. (1)

Three letters are associated with 20th century disasters at sea: SOS. Even though those three letters are forever associated with sea tragedies, they were not the original distress call used by wireless operators. In fact, one of the more famous modern sea disasters, the sinking of the Titanic, initially used three different letters that were the original distress call: CQD.

Monday, 15 April 1912, 1:40 am

SOS SOS CQD CQD MGY We are sinking fast passengers being put into boats MGY. (2)

CQD

Wireless operators using Morse Code send all kinds of messages, and obviously one that they hope to never send is a distress call. The original distress code wireless operators would send out was CQD. So, what does CQD mean?

We assume that SOS means “Save Our Ship” (it actually doesn’t), so what does CQD mean? CQD has been said to mean “Come Quick Distress.” However, the first two letters “CQ” are used by radio operators when they make a transmission, not just in times of emergency. The letter D added after those two letters stands for “Distress.” CQD was first proposed by inventor Guglielmo Marconi as a distress code in 1904, but then was later replaced by the simpler SOS around 1908. In Morse Code, CQD is (_._. _ _ ._ _..) whereas SOS is much simpler to send and receive: (three dots, three dashes, three dots).

According to the online Boat Safe article “What does SOS mean?” although there are all kinds of meanings people have given to SOS, it really has no literal meaning other than alerting others to an emergency.

The Marconi Yearbook of Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony, 1918, states:

“This signal [SOS] was adopted simply on account of its easy radiation and its unmistakable character. There is no special signification in the letters themselves, and it is entirely incorrect to put full stops between them [the letters].”

All the popular interpretations of SOS, such as “Save Our Ship,” “Save Our Souls,” or “Send Out Succor” are simply not valid. Stations hearing this distress call were to immediately cease handling traffic until the emergency was over and were likewise bound to answer the distress signal. (3)

By 1912, SOS had been in use for four years – however, British ships still used CQD. Titanic’s wireless operators initially sent out the distress call of CQD before deciding on using both distress codes, CQD and SOS. (4)

(Note: MGY was Titanic’s registered call sign, used to identify its messages as coming from that ship.)

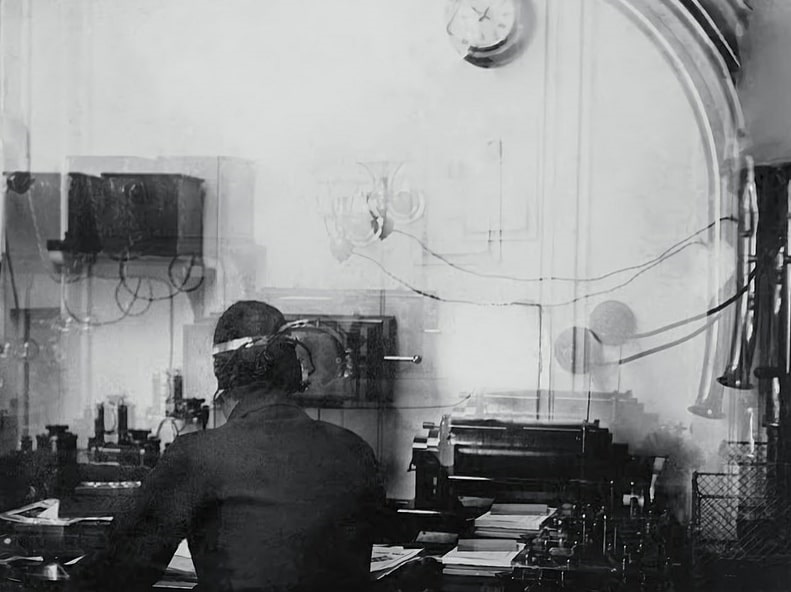

John “Jack” George Phillips and Harold Bride

It makes sense that the Titanic’s senior wireless operator, John George Phillips, would send out the Marconi-approved distress call of CQD. Marconi’s company outfitted ships of the day with their equipment, and Phillips had graduated from the Marconi Company’s Wireless Telegraphy Training School. Prior to his job on the Titanic, Phillips had worked on several ships, including the Lusitania. (5)

On board the Titanic, wireless operators Phillips and Harold Bride kept track of commercial traffic, including warnings of icebergs as well as sending out messages from passengers. Bride woke Phillips just before midnight on April 14th to start his shift – when suddenly Captain Smith came into the wireless room and asked that a distress signal be sent.

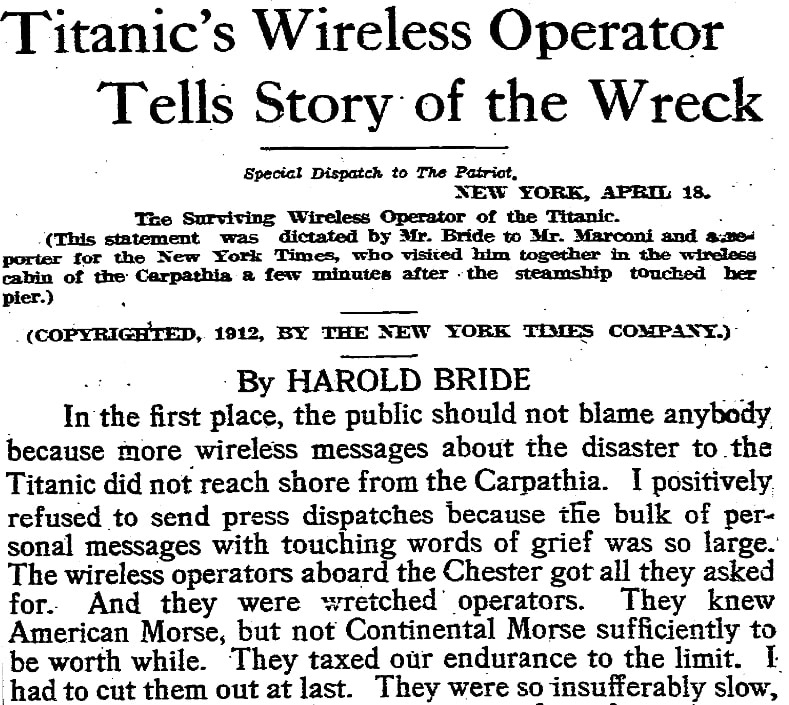

Harold Bride’s Titanic survival story as told to Guglielmo Marconi was printed in U.S. newspapers, and provides us with an eyewitness account of the wireless room and the aftermath as the events unfolded. What’s striking about the interview is that it’s obvious that Bride and Phillips didn’t initially understand the gravity of the situation. After Captain’s Smith’s request for a distress call, Phillips asked Bride what he should send and it was decided to use CQD – but after about five minutes Bride joked with Phillips and Captain Smith that they should send SOS: “It’s the new call and it may be your last chance to send it.” As time went on, the men realized the tragedy that was unfolding was no joke.

Monday, 15 April 1912, 1:45 am

Titanic to Carpathia: Come as quickly as possible. Engine room filling up to the boilers. TU OM GN (thank you old man good night). [Last message from Titanic to Carpathia.] (6)

Phillips and Bride sent out a distress signal and information about the ship’s condition up until 2:00 am, when Captain Smith relieved them of their duties. (7) Although Phillips and Bride made it to an upturned Titanic lifeboat, Phillips sank beneath the water and perished. He was 25 years old.

Marconi’s Technology

There’s no doubt that the sinking of the Titanic is one of the biggest maritime tragedies of the 20th century. But we also need to remember that the loss of life would have been much greater if it weren’t for the ship’s wireless technology that could send a radio signal over a radius of 350 miles. About 710 of the estimated 2,224 passengers and crew were saved – and that credit goes in part to Guglielmo Marconi, whose equipment and operators were on board the Titanic.

Prior to wireless technology, ships were on their own for the most part when tragedy struck. But with Marconi’s invention, the wireless operators onboard the Titanic were able to send out a distress call for two hours. Although many ships who heard the calls were not close enough to respond, eventually the RMS Carpathia did arrive after the Titanic’s sinking to rescue those passengers floating in lifeboats. While there has been some criticism of Phillips, the fact of the matter is his and Bride’s work meant that over 700 people survived the sinking of the Titanic. Bride was also instrumental in helping the wireless operator on the Carpathia send out messages about the sinking after his rescue.

14-15 April 1912

This year marks the 109th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic. You can read the wireless messages that Jack Phillips sent from the Titanic on several websites, including the Nova Scotia website Titanic.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Were any of your ancestors onboard the Titanic? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

_____________

(1) Foster, John Wilson. The Titanic Reader. New York: Penguin Books, 1999, p. 72.

(2) Foster, John Wilson. The Titanic Reader. New York: Penguin Books, 1999. p. 75.

(3) “What does SOS mean?” Boat Safe (https://www.boatsafe.com/meaning-sos/: accessed 12 April 2021).

(4) Ibid.

(5) “Mr. John George Phillips,” Encyclopedia Titanica.

(6) Foster, John Wilson. The Titanic Reader. New York: Penguin Books, 1999, p. 75.

(7) “The Story of John George “Jack” Phillips,” The National Archives (accessed 11 April 2021).

Related Articles:

What a captivating read! The details surrounding the Titanic’s final moments are both haunting and fascinating. It’s hard to imagine the panic and confusion that ensued. Thank you for shedding light on such a pivotal moment in maritime history.

Thank you for taking the time to read the article and comment. I agree with you that history is haunting and fascinating, and there are so many factors that could be studied.