Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry writes more about a brave Quaker woman who defied Puritan officials in Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1600s: Deborah (nee Buffum) Wilson. Melissa is a genealogist who has a website, americana-archives.com, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

Today I resume my series focusing on three brave 17th century Quaker women: Lydia Wardwell, Deborah Wilson, and Margaret Brewster. They were among the many dames who protested the orthodox Puritan church in Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1600s.

To recap: My first two stories covered Quakeress Lydia (nee Perkins) Wardwell of Hampton, New Hampshire, wife of Eliakim Wardwell, who went naked into Newbury Meeting House in 1663 to protest the actions of Puritan officials. Read “Quakers Gone Wild” Part 1 and Part 2.

And Part 3 recalled another act of nude protest carried out in June of 1662 by Deborah (nee Buffum) Wilson, who walked through the town of Salem, Massachusetts, naked as a sign of the spiritual bareness of the orthodox church. When Wilson pulled her Godiva act, she was accompanied by her mother Thomasin (nee Ward) Buffum and sister Margaret (Buffum) Smith, wife of John Smith, both fully clothed, to support her cause.

The following cartoon depicts the Quakers of the 17th century and includes all three subjects of this series. The Quaker lot were viewed by many historians as loud troublemakers, dissenters, and unruly heretics (more on this below).

An author reviewing James Duncan Phillips’s book Salem in the Seventeenth Century, published in 1933, features chapters dedicated to the persecution of the early Quakers.

A review of Phillips’s book appeared in the Springfield Republican with this headline: “Period When Quakers Had Their Ears Cut Off and Were Hanged – Famous Town’s Beginnings.”

Phillips, like many antiquarians, believed the Quakers to be fanatical and unruly. And nudist Deborah Wilson was no different.

In the eyes of 17th century Puritan New England, the Quakers were a bothersome lot disrupting their well-organized system, and no matter what punishments (ear cropping, branding, whipping, hanging, and banishment) the authorities laid on them, they just kept coming.

In this book review, the reviewer quotes Phillips regarding our subject:

“[The Quakers] were a trial, and I suspect that Deborah Wilson, a ‘young woman of very modest and retired life, going through the town of Salem naked as a sign’ must have been a bit of embarrassment to the authorities, and it seems difficult to get away from the conclusion that she was immodest, bold, and exceedingly impudent.”

The reviewer then writes:

Yet it is possible that she was merely deluded – as deluded, for instance, as the magistrates and leading citizens were in the witchcraft period some 40 years later.

Wilson was arrested before she made the full rounds of the village and Judge William Ha[w]thorne ordered her punished, according to court records, for:

“her barbarous and unhuman going naked through the town, is sentenced to be tied at a cart’s tail with her body naked downward to her waist, and whipped from Mr. Gidneyes’ gate till she come to her own house, not exceeding thirty stripes, and her mother [Thomasin] Buffum and her sister [Margaret, wife of John] Smith, that were abetted to her, etc., to be tied on either side of her, at the cart’s tail, naked to their shifts to the waist, and accompany her.”

Another layer to the story of Deborah Wilson’s naked protest walk is told in George Bishop’s “New-England Judged, by the Spirit of the Lord.”

Bishop claims the harsh punishment the court placed on Deborah Wilson was so severe it caused the constable ordered to carry out the judgement, Daniel Rumbal, uneasiness.

![Illustration: example of being whipped “at the cart’s-tail,” from the “American” magazine, Springfield, [etc.], Crowell-Collier Pub. Co. [etc.], 1876-1956. Credit: New York Public Library.](http://blog.genealogybank.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/illustration-0529-2024-whipped-at-carts-tail.jpg)

“Daniel Rumbal, who had bowels of compassion, could not do to her as you would, for which he was questioned by your Court; which he put off, and said, ‘He was loath to be whipped as he whipped her.’”

According to sources Rumbal allowed Robert Wilson, Deborah’s husband. to use his hat and hand as a shield on her bare flesh to protect her from the whip.

However, there are other accounts which suggest Rumbal had a romantic crush on the nudist. Heather Wilkinson Rojo, a 9th general descendant of Deborah Wilson, reveals more on this story in “A Love Story Too Sad for Valentine’s Day.”

There is no doubt that Debora Wilson’s bold act of civil disobedience made much talk in town for years to follow!

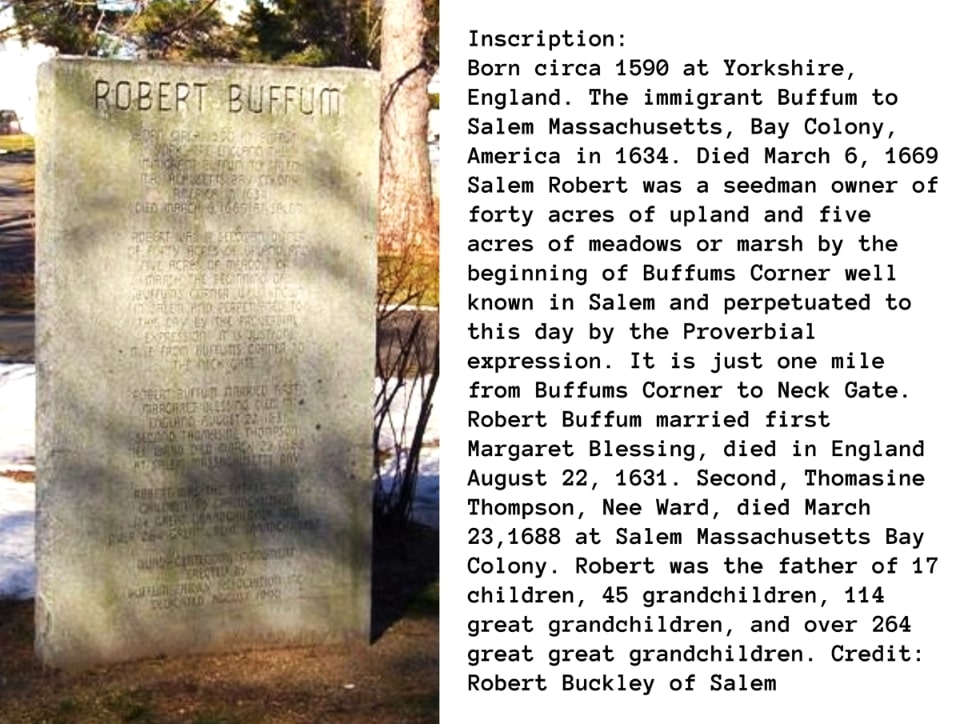

Here is a photo of the grave marker for Deborah (Buffum) Wilson’s father, Robert Buffum (1590-1669), located in Harmony Grove Cemetery, Salem, Massachusetts. In 1991, the Buffum Family Association erected and dedicated this 400th anniversary memorial to Robert.

Stay tuned for the next wild Quakeress!

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: “Cassandra Southwick in court before the magistrates,” from the Boston Globe, 23 October 1923.

Related Articles:

- 17th Century Quaker Women Gone Wild (part 1)

- 17th Century Quaker Women Gone Wild (part 2)

- 17th Century Quaker Women Gone Wild (part 3)

- Nathaniel Sylvester, ‘Lord of Shelter’ for 17th Century Quakers

- A Monument for Persecuted Quakers Upsets Salem, MA

- Persecuted Quakers in Colonial America

- Persecuted Quakers in Colonial America, Part II

- Persecuted Quakers in Colonial America, Part III

- The Coming of the Quakers, Part I

- The Coming of the Quakers, Part II

- Early Quaker Meetings Raided by Salem Authorities

- Rare Quaker Bible from Early Colonial Days