Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry writes more about three brave Quaker women who defied Puritan officials in Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1600s. Melissa is a genealogist who has a website, americana-archives.com, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

Today I continue my series focusing on three brave 17th century Quaker women: Lydia Wardwell, Deborah Wilson, and Margaret Brewster. They were among the many dames who protested the orthodox Puritan church in Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1600s.

To recap: My first two stories covered Quakeress Lydia (nee Perkins) Wardwell of Hampton, New Hampshire, wife of Eliakim Wardwell, who went naked into Newbury Meeting House in 1663 to protest the actions of Puritan officials. Read “Quakers Gone Wild” Part 1 and Part 2.

The following cartoon depicts the Quakers of the 17th century and includes all three subjects of this story series. The Quaker lot were viewed by many historians as loud troublemakers, dissenters, and unruly heretics (more on this below).

This act of nude protest had earlier been carried out (in June of 1662) by Deborah (nee Buffum) Wilson, who walked through the town of Salem, Massachusetts, naked as a sign of the spiritual bareness of the orthodox church. When Wilson pulled her Godiva act, she was accompanied by her mother and sister (both fully clothed) to support her cause.

Wilson was arrested before she made the full rounds of the village and Judge William Ha[w]thorne ordered her punishment, according to court records, for:

“her barbarous and unhuman going naked through the town, is sentenced to be tied at a cart’s tail with her body naked downward to her waist, and whipped from Mr. Gidneyes’ gate till she come to her own house, not exceeding thirty stripes, and her mother [Thomasin] Buffum and her sister [Margaret, wife of John] Smith, that were abetted to her, etc., to be tied on either side of her, at the cart’s tail, naked to their shifts to the waist, and accompany her.”

Wilson was protesting the persecution of her family and friends at the hands of the Puritans. Her plight was addressed in a letter written by Quaker poet John Greenleaf Whittier in 1881. A portion of the letter was published in the newspaper and furnished more explanation for Wilson’s protest and a defense of her and other Quakers who challenged the Puritan order.

Whittier wrote:

She [Deborah Wilson] had seen her friends and neighbors scourged naked through the street, among them her brother [Joshua Buffum], who was banished on pain of death. She, like all Puritans, had been educated in the belief of the plenary inspiration of Scripture, and had brooded over the strange “signs” and testimonies of the Hebrew prophets. It seemed to her that the time had arrived for some similar demonstration, and that it was her duty to walk abroad in the disrobed condition to which her friends had been subjected, as a sign and warning to the persecutors. Whatever of “indecency” there was in these cases was directly chargeable upon the atrocious persecution. At the door of the magistrates and ministers of Massachusetts must be laid the insanity of the conduct of these unfortunate women.

Whittier’s letter was a response to Dr. George E. Ellis, who criticized the poet’s poem “The King’s Missive” in a lecture before the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Dr. Ellis asserted that the Quakers were all “of low rank, of mean breeding, and illiterate.’ Further, “they courted persecution and were a pestilent brood of ranters, disturbers of the public peace, and dreaded by the leaders of the infant Commonwealth as they would have dreaded the cholera.” His description is much like the one in the cartoon above.

In his letter, Whittier further wrote:

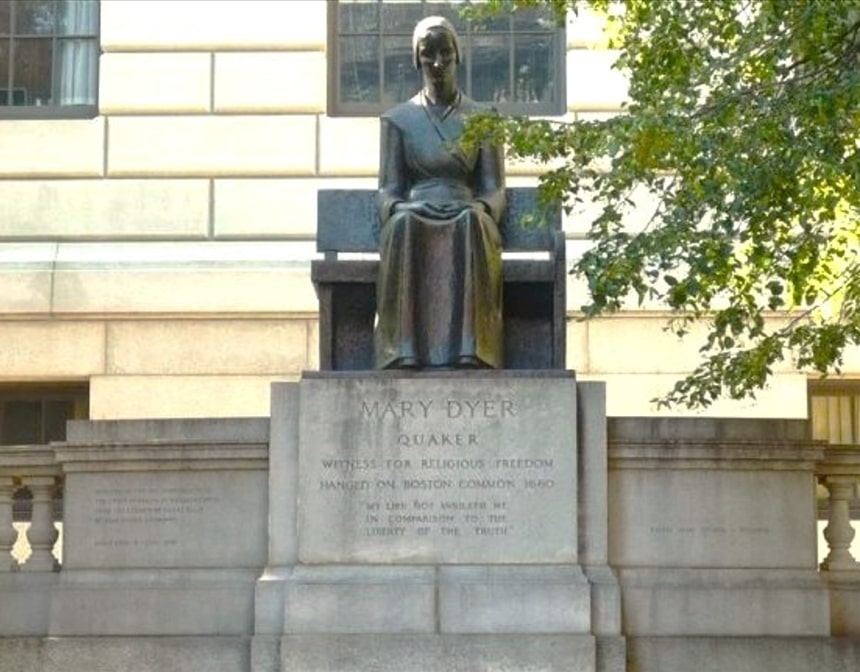

The charge that the Quakers who suffered were “vagabonds” and “ignorant, low fanatics,’ is unfounded in fact. Mary Dyer, who was executed, was a woman of marked respectability. She had been the friend and associate of [Massachusetts Governor] Sir Henry Vane and the ministers [Rev. John] Wheelwright and [Rev. John] Cotton.

A statue in honor of Mary Dyer was erected by the Art Commission of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, from the legacy of Zenas Ellis of Fair Haven, Vermont. It was dedicated on 9 July 1959 and carries this inscription:

Mary Dyer

Quaker

Witness for Religious Freedom

Hanged on Boston Common – 1660

“My life not availeth me in comparison to the liberty of the truth.”

Whittier also wrote in his letter:

The papers left behind by the three men who were hanged [Quakers William Robinson and Marmaduke Stevenson in 1659, and Quaker William Leddra in 1661] show that they were above the common class of their day in mental power and genuine piety. John Rous, who in execution of his sentence, had his right ear cut off by the constable in the Boston jail, was of gentlemanly lineage, the son of Colonel Rous of the British army, and himself the betrothed of a high-born and cultivated young English lady. Nicholas Upsall was one of Boston’s most worthy and substantial citizens, yet was driven, in his age and infirmities, from his home and property into the wilderness.

The Buffum family were no commoners either! More on that in the next story, so stay tuned – Deborah (nee Buffum) Wilson’s drama and a love twist…

Note: The “sign” for going naked is explained in Augustus Charles Bickley’s book “George Fox and the Early Quakers,” and in Heather E. Barry’s article “Naked Quakers Who Were Not So Naked. Seventeenth-Century Quaker Women in the Massachusetts Bay Colony” published in the Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 43, No. 2.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: “Cassandra Southwick in court before the magistrates,” from the Boston Globe, 23 October 1923.

Related Articles:

- 17th Century Quaker Women Gone Wild (part 1)

- 17th Century Quaker Women Gone Wild (part 2)

- Nathaniel Sylvester, ‘Lord of Shelter’ for 17th Century Quakers

- A Monument for Persecuted Quakers Upsets Salem, MA

- Persecuted Quakers in Colonial America

- Persecuted Quakers in Colonial America, Part II

- Persecuted Quakers in Colonial America, Part III

- The Coming of the Quakers Part I and Part II

- Early Quaker Meetings Raided by Salem Authorities

- Rare Quaker Bible from Early Colonial Days