Introduction: Gena Philibert-Ortega is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.” In this blog article – in honor of Women’s History Month and the just-ended Black History Month – Gena searches old newspapers to learn more about four African American women heroes.

Recently an image of five African American women standing together, dressed as though they are at a special event or party, has been posted on social media websites. The text accompanying that image asks what those women have in common. The answer? They are all astronauts.

That got me thinking about other strong, smart, innovative African American women in history, whose heroism has lasting impacts on all of us today. Putting together a short list of African American women heroes is hard. There are so many to choose from, but below is a list of four women everyone should know more about.

Ida B. Wells (1862-1931)

Born in 1862, Ida B. Wells was an educator, reporter, and activist, probably best known for her activism against lynching. Her civil rights activism was sparked in 1884 when she bought a first class ticket to Nashville, boarded the train in Memphis, and was told by the conductor that she would need to move to the African American car. She refused and was forcibly removed from the train.

A newspaper article two years later reported the story as Wells was waiting for the decision on her lawsuit against the railroad. The newspaper reminded readers that:

Miss Wells, some time ago, was shamefully insulted and abused by an ill-bred conductor who showed no feelings toward a woman belonging to the race. Finding Miss Wells seated in the same car with white ladies, the ruffian seized this unoffending lady, dragged her to the platform of the car and threw her off.

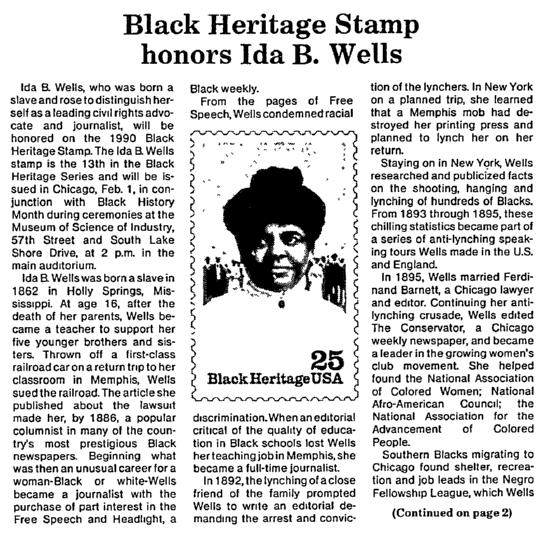

Two important outcomes from that incident: she won her lawsuit against the railroad; and she started writing about racism and injustice. Her activism focused on the practice of lynching after the lynching death of a close friend. She went on speaking tours to inform the public, and to raise money for detectives to investigate lynching cases.

Wells eventually owned a few African American newspapers, including the Conservator, purchased from her newspaper publisher husband Ferdinand Barnett. Ida B. Wells-Barnett died in 1931 after a life of fighting for civil rights.

Bessie Coleman (1892-1926)

When we think of early women aviatrix we tend to automatically think of Amelia Earhart – but Bessie Coleman was flying before Earhart. Coleman may not have piloted a transatlantic flight as Earhart famously did, but her determination to obtain a pilot’s license paved the way for other African American women.

Coleman first heard about aviation from returning World War I pilots during her time in Chicago working as a manicurist. She wanted to pursue her pilot’s license but no aviation school in America would accept an African American woman – so with some financial backing and after learning some French, she traveled to France and earned her pilot’s license there. She became the first woman of African American and Native American descent to hold a pilot’s license, as well as an international pilot’s license.

Stunt and barnstorming exhibitions were one of the ways pilots of this time period could make a living. Coleman took part in these events and hoped to one day have enough money to open an aviation school for young African Americans. Unfortunately, Bessie Coleman’s life was cut short at the age of 34 as she was preparing for an airshow. Surveying the area for a parachute jump she was going to do the next day, she was a passenger in a plane piloted by William D. Willis. Coleman fell to her death when the plane unexpectedly went into a dive. The plane crashed, killing the pilot as well.

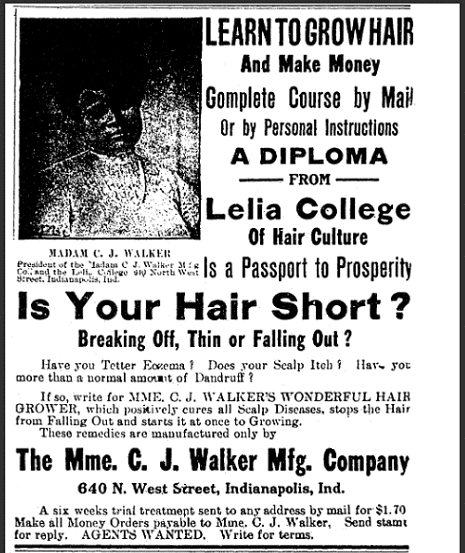

Madame C. J. Walker (1867-1919)

Inventions often are the result of the inventor trying to solve a problem. In the case of Madame C. J. Walker, the problem was something she was experiencing – and her answer to that problem made her a successful business woman.

Sarah Breedlove was born in 1867 to former slaves. Orphaned at the age of 7, married at 14 and a widow with a two-year-old daughter at 20 years of age, Sarah decided to move near her brothers who worked as barbers. Suffering from a scalp ailment, Walker started devising her own hair care products, as well as using those produced by an African American business woman, Annie Malone. Sarah would become a sales agent for Malone and continue to develop her own hair care products. After marrying her third husband, Charles Joseph Walker, she changed her name to Madame C. J. Walker and started a business selling her hair products with marketing help from her newspaperman husband.

Walker traveled throughout the South, demonstrating and promoting her hair products and eventually hiring saleswomen.

Madame Walker’s business empire grew to include a mail order business, factory, laboratory, hair salon and beauty college.

Madame C. J. Walker’s company was so successful that she became the first female self-made millionaire in the U.S. She made a difference in her and her family’s life but also in the greater community. When she passed away in 1919, Madame C. J. Walker through her will donated a large portion of her estate to African American charities.

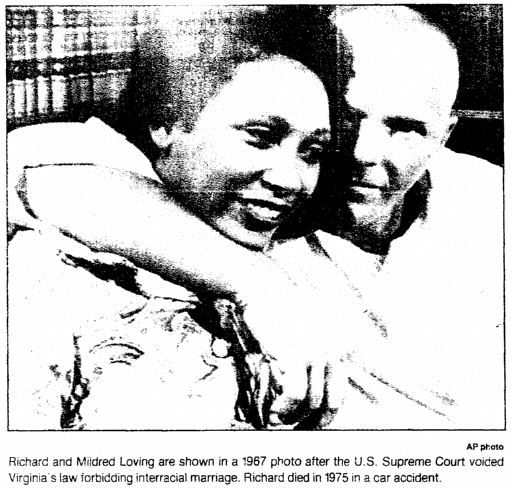

Mildred Jeter Loving (1939-2008)

Unlike the other three women I’ve written about in this article, Mildred Loving didn’t actively seek out the role of activist or innovator. But it was in the simple act of loving her husband that she made an enormous change that affected a nation and paved the way for marital civil rights. Mildred is best known for breaking the law.

Mildred Jeter, a woman of African American and Native American descent, was just a teenager when she married Richard Loving in 1958 in Washington D.C. After their wedding, they returned home to Virginia to start their lives together as husband and wife. Shortly thereafter in the early morning hours of 11 July 1958 the sleeping Lovings were startled awake to find the county sheriff and his deputies in their bedroom.

Their marriage violated Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924 which forbade marriage between the races. Both Richard and Mildred were arrested and spent time in jail before being ordered to leave the state for 25 years. The Lovings left Virginia and returned to Washington D.C.

In 1963 the Lovings decided to take action with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union. Their case against the Virginia law was eventually heard in the United States Supreme Court. On 12 June 1967 the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Lovings, declaring that the Virginia law violated the Equal Protection Clause and Due Process of the 14th Amendment, thus invalidating laws against interracial marriage.

Just a Few

My four choices above are just a few of the African American women heroes who’ve made a difference in their community and for all of us. Newspapers, such as the collection in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, give us a way of following the heroes’ journeys and give us some of that rich background about their lives. What African American women heroes did I miss? Let us know in the comments.

Related Articles: