Introduction: In this article, Gena Philibert-Ortega searches old newspapers to learn more about one of her personal heroes: San Diego librarian Clara Breed. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

Heroes come in all packages. While we envision heroes accomplishing superhuman feats with their bulging muscles, they are often the exact opposite. When you think of an occupational “hero,” police officers, soldiers or firefighters may come to mind.

But there’s no doubt in my mind that librarians are also heroes. As finders of information, they have the ability to open up new worlds for the community they serve. Some librarians do even more than that, as in the case of San Diego librarian Clara Breed (1906-1994).

Clara Estelle Breed

Clara Estelle Breed was born in Iowa in 1906. As a young woman, she and her mother moved to California in 1920 after the death of her father. In California, she attended high school and college, graduating with a degree in library science. This brief newspaper article notes that the then 19-year-old college student had just “entertained four of her Pomona college friends at a house party over the week-end.”

It wasn’t too long after she graduated that she was hired as a children’s librarian for the San Diego Public Library, in 1928.[i] As children’s librarian one can imagine she was well-loved by her young charges. Far from the stereotypical librarian who is constantly shushing everyone, a newspaper article printed years after her retirement recounted that Breed welcomed the children into the library with her actions that included taking down all of the “Quiet!” signs. She believed that “sound-proofing and carpeting were better than discouraging children.”

World War II

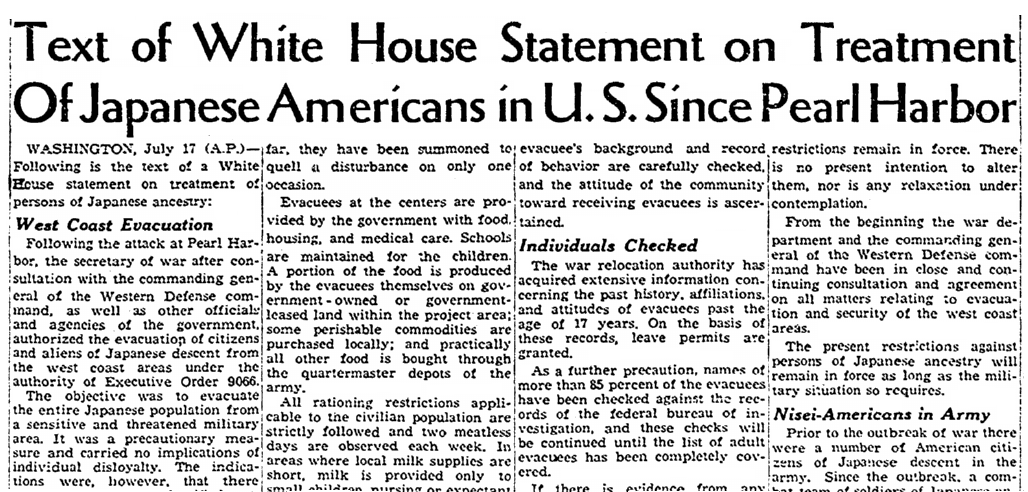

By the time the U.S. entered World War II, Breed had served the San Diego Library system for over a decade. The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 led to the 1942 Executive Order 9066: the forced incarceration of Japanese American citizens. Japanese Americans, many of whom had never even been to Japan, experienced severe racial hatred and forced evacuation just because of their heritage. Pearl Harbor would have a lasting, profound effect on Americans – including the young children that Breed had befriended at the library who were of Japanese descent.

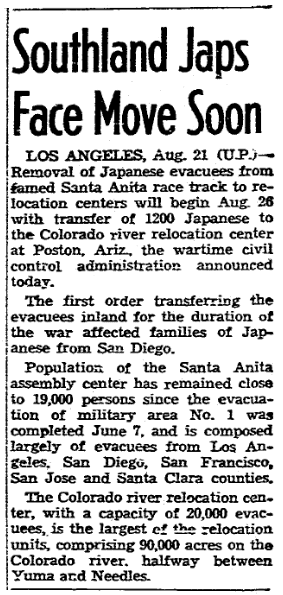

The children that Breed had come to consider “her children” were sent to Santa Anita Racetrack in Southern California prior to being transported to internment camps like Poston in Arizona. “From March 27 until October 27, 1942, more than eighteen thousand people from Los Angeles, San Diego and Santa Clara counties lived in Santa Anita. In just sixty days it became the thirty-second largest community in California.”[ii] Japanese American families were housed in the horse stalls until it was time to pack up and relocate.

Prior to leaving San Diego, Japanese American children came to the library to return books and their library cards. Clara Breed, their librarian, was prepared. As she said her goodbyes she provided a stamped, addressed postcard to each child so that they could write to her and let her know how they were doing – and she in return would provide a book to read.

Later, Breed would write a magazine article about that emotional day, the West Coast Japanese Americans who were sent to internment camps, and the libraries that eventually serviced those camps. In her article “Americans with the Wrong Ancestors,” she wrote:

A little more than a year ago, libraries in California, Oregon, and Washington were swept clean of some of their most enthusiastic borrowers – Americans whose parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents happened to emigrate from the wrong country, Japan. They were not a large part of the population. There are only 135,000 Japanese in the whole country, and only 100,000 were living on the West Coast. Of these, two-thirds were American-born and therefore citizens; one-third aliens who under our laws could never become citizens.[iii]

Breed ended her article by quoting President Franklin D. Roosevelt:

In a letter congratulating the War Department for its decision to recruit Japanese Americans in a combat unit, President Roosevelt wrote, “The principle on which this country was founded and by which it has always been governed is that Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart; Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry.”[iv]

The Letters

It’s unlikely that Breed anticipated what those penny postcards she provided to “her” children would lead to, but the Japanese American children of San Diego wrote to her, and continued writing to her. She reciprocated by replying with letters, books, and other supplies. She wrote in a 1943 article for Library Journal that although the letters reflected the children’s growing “hardening and consciousness of race,” they were holding “fast in their faith in America.”

The most important aspect of Breed’s writing to the children was that she was a reminder of someone who cared about them outside of the camps. By war’s end she was no longer the children’s librarian, having been promoted to head librarian for the city of San Diego. However, she continued to stay in contact with many of those children that she wrote to during the war.

Because letters are ephemeral, the entire story of Clara Breed’s letters cannot be told. She had kept 300 letters sent to her but only one of her letters to a child has been found.[v]

Later Years

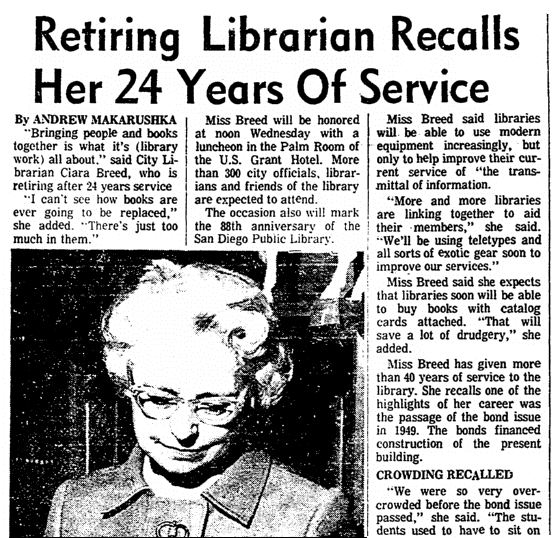

Clara Breed retired from the San Diego Public Library in 1970. Her 24-year tenure as City Librarian was marked by many accomplishments, including the building of a new library.

Clara Breed’s retirement from the library didn’t mean that her connection to it was severed. After retirement, she published a history of the library titled Turning the Pages: San Diego Public Library History 1882-1982, which included a chapter about the war years and a “brief mention of the postcards and her ‘children’.”[vi]

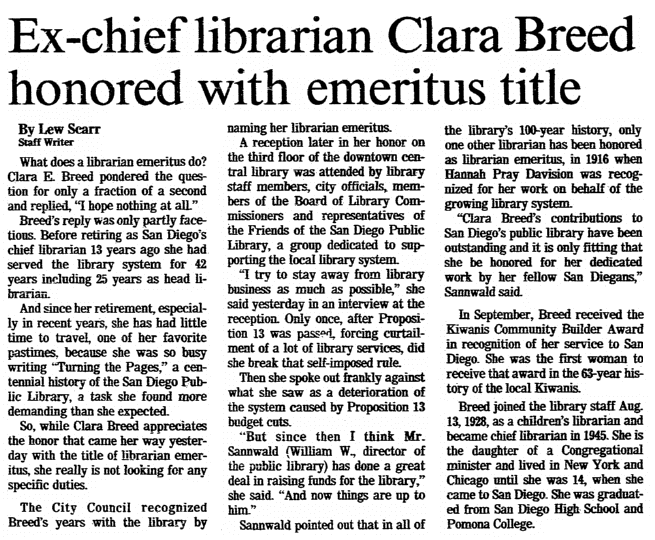

In 1983 the retired Clara Breed was honored for her work by being named Librarian Emeritus. Only one other librarian had been bestowed this honor. In a response worthy of a woman retired for over a decade, Miss Breed answered a reporter’s question regarding the specific duties of a librarian emeritus with the answer, “I hope nothing at all.”

In 1988, as she packed up her home so that she could move into a retirement home, Breed found those World War II letters stored for over 40 years. Having limited space in her new home, she called one of “her children” and asked if she would take the letters. Elizabeth Kikuchi Yamada accepted those letters, which included some that she herself had written. Yamada donated them and some other items to where they reside today, at the Japanese American National Museum.[vii]

Clara Breed died on 8 September 1994 at the age of 88 years. But her legacy lives on in many ways, including the Clara Breed Collection at the Japanese American National Museum – which houses over 240 letters written by Clara’s “children.” You can see the digitized copies on the Museum’s website.

———————-

[i] Clara Breed. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clara_Breed.

[ii] Oppenheim, Joanne. Dear Miss Breed. True Stories of the Japanese Americans Incarceration During World War II and a Librarian Who Made A Difference. New York: Scholastic (2006). Page 63.

[iii] Breed, Clara. Americans With the Wrong Ancestors. The Horn Book. http://www.hbook.com/1943/07/choosing-books/horn-book-magazine/americans-wrong-ancestors/#_

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Oppenheim, Joanne. Dear Miss Breed. True Stories of the Japanese Americans Incarceration During World War II and a Librarian Who Made A Difference. New York: Scholastic (2006). Page 287.

[vi] Ibid, Page 238.

[vii] Ibid, Page 256.