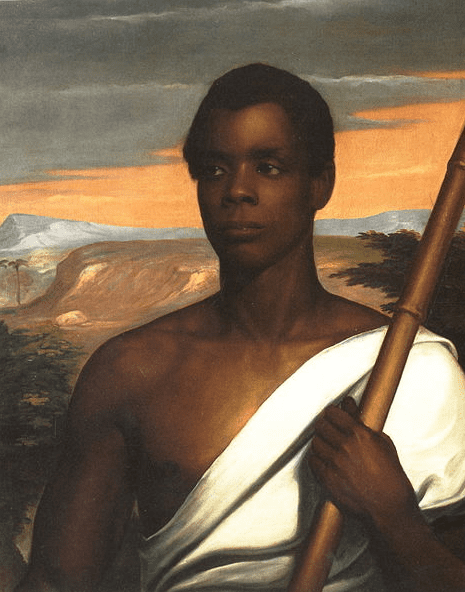

In a case closely watched by the American public, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on 9 March 1841 in favor of the African petitioners in the famous Amistad case, a slave revolt led by Sengbe Pieh (Joseph Cinqué), a West African man of the Mende people.

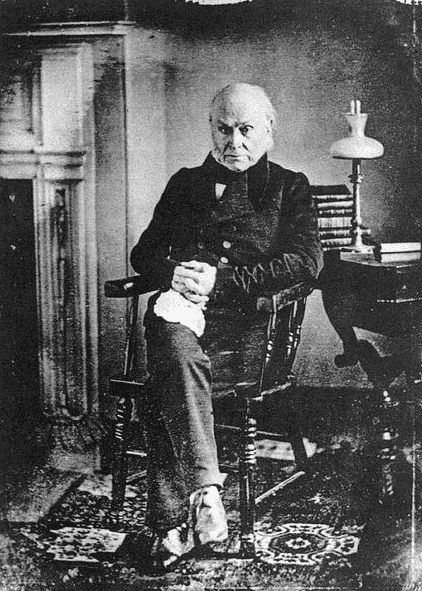

The Court’s decision was influenced in no small part by the eight and a half hours of powerful testimony presented by 73-year-old John Quincy Adams (ex-president and then-congressman from Massachusetts). Adams and others argued that, since the Atlantic slave trade was illegal, the Africans were not the legal property of their Spanish masters but rather free men who had been kidnapped and illegally transported across the ocean.

The slaves had rebelled on board the ship Amistad off the Cuban coast, but the pilots tricked them and, instead of sailing back to Africa, steered the ship up the United States coast.

The Amistad was captured off Long Island by the U.S.S. Washington on 26 August 1839. Ironically its commander, Lieutenant Thomas R. Gedney, started the legal proceedings by claiming he had salvage rights to the ship and the slaves as his property, and he desired to sell them for a profit. A host of other parties, including Spaniards and the Spanish government, filed lawsuits as well, and the intricate, tangled case ended up before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Abolitionists rallied to the Africans’ cause; an interpreter was found to learn their story, and attorneys agreed to represent them. When the case rose before the Supreme Court John Quincy Adams offered to plead their case, did so magnificently, and refused any payment. The Africans were free to remain in the United States or return to Africa. In 1842 the 36 surviving Africans returned to Africa, their voyage paid by abolitionists’ donations.

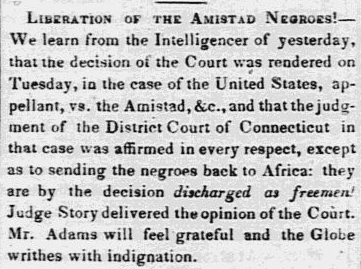

Here is a transcription of this article:

Liberation of the Amistad Negroes!

We learn from the Intelligencer of yesterday, that the decision of the Court was rendered on Tuesday, in the case of the United States, appellant, vs. the Amistad, &c., and that the judgment of the District Court of Connecticut in that case was affirmed in every respect, except as to sending the negroes back to Africa: they are by the decision discharged as freemen! Judge Story delivered the opinion of the Court. Mr. Adams will feel grateful and the Globe writhes with indignation.

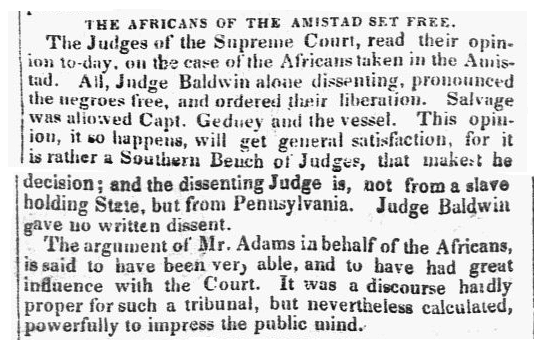

The Africans of the Amistad Set Free

The Judges of the Supreme Court read their opinion to-day, on the case of the Africans taken in the Amistad. All, Judge Baldwin alone dissenting, pronounced the negroes free, and ordered their liberation. Salvage was allowed Capt. Gedney [of] the vessel. This opinion, it so happens, will get general satisfaction, for it is rather a Southern Bench of Judges that makes the decision; and the dissenting Judge is not from a slave holding State, but from Pennsylvania. Judge Baldwin gave no written dissent.

The argument of Mr. Adams in behalf of the Africans is said to have been very able, and to have had great influence with the Court. It was a discourse hardly proper for such a tribunal, but nevertheless calculated powerfully to impress the public mind.

Here is a transcription of this article:

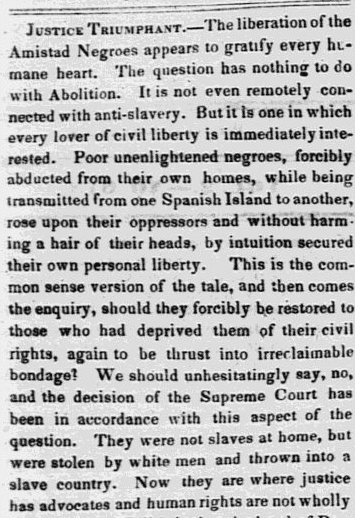

Justice Triumphant

The liberation of the Amistad Negroes appears to gratify every humane heart. The question has nothing to do with Abolition. It is not even remotely connected with anti-slavery. But it is one in which every lover of civil liberty is immediately interested. Poor unenlightened Negroes, forcibly abducted from their own homes, while being transmitted from one Spanish Island to another, rose upon their oppressors and without harming a hair of their heads, by intuition secured their own personal liberty. This is the common sense version of the tale, and then comes the enquiry, should they forcibly be restored to those who had deprived them of their civil rights, again to be thrust into irreclaimable bondage? We should unhesitatingly say, no, and the decision of the Supreme Court has been in accordance with this aspect of the question. They were not slaves at home, but were stolen by white men and thrown into a slave country. Now they are where justice has advocates and human rights are not wholly disregarded. Well it is that the hand of Providence, rather than blind chance, guided their little tempest-tossed vessel upon the shores of North America, rather than upon the islands in the Gulf of Mexico. Now they are free. Then they would have been thrown into irreclaimable slavery.

Related Articles: