Hollywood was booming in the first quarter of the 20th century as silent films became one of America’s favorite entertainments. Then on 6 October 1927 something magical happened that radically transformed movies and doomed the silent film era: The Jazz Singer, the first feature-length movie containing songs and dialogue and starring singing sensation Al Jolson, electrified the audience gathered at the Warner Bros.’ theater in New York City for the premiere.

It did not happen overnight, but silent movies were on their way out: “talkies” were what film audiences wanted to see.

The film critic for Life magazine, Robert E. Sherwood, in a review of The Jazz Singer reprinted in the newspaper article below, wrote that the movie “is lifted, by the sheer magic of Jolson’s voice, to the levels of extraordinary entertainment.”

Sherwood made this prescient comment:

I may be wrong in assuming that talking movies are about to become an accomplished fact. Perhaps pictures like The Jazz Singer will prove to be no more than freakish novelties, and that the great bulk of the film fans will remain faithful to the old order. But I doubt it. There is too much emotional appeal in the human voice.

How right he was.

Befitting something as monumental and groundbreaking as the legendary first “talkie” movie, there is a great deal of drama, human interest and tragedy surrounding the production of The Jazz Singer. As with most legends, there is also a great deal of public misconception.

First of all, The Jazz Singer was not the first movie that had sound. Some earlier movies had dialogue, but they were all short films. Some earlier, longer films had instrumental music and sound effects. But The Jazz Singer was the first feature-length movie to contain a sound score, sound effects – and feature actual dialogue and singing. As such, it was something new and bold, and took audiences by storm.

Even so, The Jazz Singer was not an overnight success. It slowly gained an ever-growing audience and increased distribution, until it eventually did so well that Warner Bros., a studio experiencing financial difficulties at the time, managed to earn a profit on the (then-staggering) $422,000 it cost to produce the film.

Although it made its mark on history as the first “talkie” film, there is hardly any talking in the movie – a total of only about two minutes. For all the other “speech” in the film, The Jazz Singer employs the standard silent film technique of caption cards to express what the characters are saying.

The very first words spoken in the movie do not occur until 17½ minutes into the film; but how powerful and prophetic they are! Jolson’s character, Jack, declares to a cabaret crowd – and, by extension, to the whole world: “Wait a minute, wait a minute, you ain’t heard nothin’ yet!”

The Jazz Singer did not immediately end the silent film era. For one thing, many theaters at the time were not equipped to handle movies with sound. In fact, many theaters that initially showed The Jazz Singer had to present it as a silent film. The majority of films released in 1928 continued to be silent films. By 1930, however, silent films were basically done.

The plot of The Jazz Singer, concerned as it is with Jewish identity, and Jewish-Americans honoring the traditions of their ancestors while adapting to the modern pace of life in America during the jazz age, reflected the views and experiences of the four Jewish Warner (born Wonskolaser) brothers Albert, Harry, Jack, and Sam, who made the film, and of its Jewish star, Al Jolson.

The New York premiere was scheduled for the day before Yom Kippur, the Jewish holiday central to the film’s story. Sadly, none of the Warner brothers were able to attend the celebratory opening because the day before, Sam – the brother who persuaded the others that talking movies were the next big thing – had died of pneumonia, and they were all in California to attend his funeral.

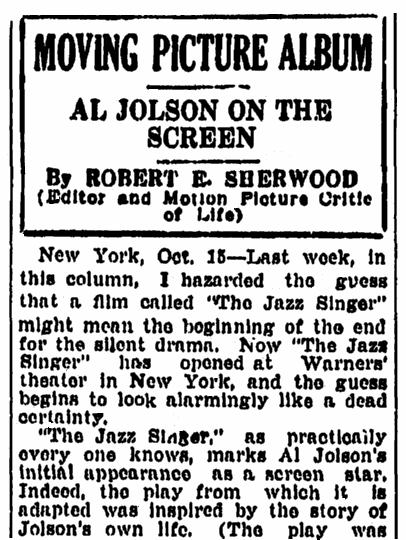

This newspaper article reprinted the influential review by Life critic Robert E. Sherwood.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Moving Picture Album

Al Jolson on the Screen

By Robert E. Sherwood

(Editor and Motion Picture Critic of Life)

New York, Oct. 15 – Last week, in this column, I hazarded the guess that a film called “The Jazz Singer” might mean the beginning of the end for the silent drama. Now “The Jazz Singer” has opened at Warners’ theater in New York, and the guess begins to look alarmingly like a dead certainty.

“The Jazz Singer,” as practically everyone knows, marks Al Jolson’s initial appearance as a screen star. Indeed, the play from which it is adapted was inspired by the story of Jolson’s own life. (The play was written by Samuel Raphaelson, and has been a stage success in the past two years.)

It tells of the Rabinowitz family, who have been cantors in synagogs [sic] for five generations and are proud of it. The youngest Rabinowitz, American born, is being groomed by his strictly orthodox father to carry on the old tradition and devote his life to the faith of his ancestors.

Young Jakie, however, has other plans. His heart beats in time to the pulse of America, and in that beat is the rhythm of jazz. Thus, when he should be in the synagog learning his chants, Jakie is strutting about an East-side café warbling, “Way down on the levee, in old Alabammy, there’s Daddy and Mammy, and Ephraim and Sammy.”

The boy is cast out as a renegade by his father, and years pass before he returns to New York to knock Broadway off its feet with his super-jazz.

Then comes the big dramatic climax. The old father is dying and calling for his son to come back to sing in the synagog on the Day of Atonement. At the same time, the theatrical world is waiting expectantly for the first appearance of the young sensation in the new Winter Garden revue.

Which shall he sacrifice – his career, or the faith of his people?

Al Jolson manages to sacrifice neither. On the lower East side he sings “Kol Nidre” in the synagog with great power and feeling, and his old father dies happy; then he jumps back to Broadway and croons “Mammy – Ma-ha-ha-ha-ha-my – the sun shines east – the sun shines west –,” as only he, of all singers that ever existed on this earth, can render it.

And the wonderful part of it is that the audience, sitting in a movie theater, can hear Al Jolson as well as see him. Due to the excellence of the Vitaphone attachment, his marvelous voice, the clapping of his hands, the nervous shuffling of his feet, the very sobs with which he punctuates his high notes come out from the shadows on the screen with an amazing semblance of reality.

For this reason, “The Jazz Singer” becomes superlatively thrilling. A mediocre picture, as mere pictures go, it is lifted, by the sheer magic of Jolson’s voice, to the levels of extraordinary entertainment.

Its first performance in New York called forth such enthusiasm as I have never before seen in a film parlor. Everyone wept, including Al Jolson, himself, who was called upon for a speech after the final fade-out. He was too overcome to tell the audience, “Folks, you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.”

Al Jolson sings six songs at various times during “The Jazz Singer.” There are also reproductions of the beautiful voice of Cantor Josef Rosenblatt.

In one scene, Jolson is seen at the piano, singing “Blue Sky” to Eugenie Besserer, who appears as his mother. At the conclusion of the song, he turns and talks to her – this being the only snatch of spoken dialog in the film.

When that scene ends, and the picture returns to the routine of subtitles and pantomime, one feels that the day of the great transformation has dawned – that the silent drama can never be silent again.

I may be wrong in assuming that talking movies are about to become an accomplished fact. Perhaps pictures like “The Jazz Singer” will prove to be no more than freakish novelties, and that the great bulk of the film fans will remain faithful to the old order. But I doubt it. There is too much emotional appeal in the human voice.

I know that, in my case, I can derive more of a thrill from one of Al Jolson’s gasps than from all the views of the United States Marine Corps coming – coming – coming.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.