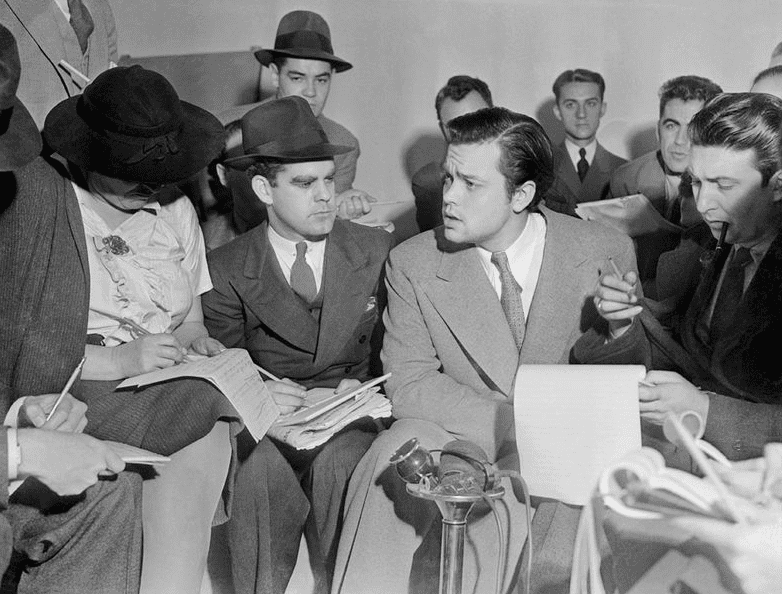

On 30 October 1938, the young, brilliant actor and director Orson Welles decided to give his Halloween radio audience a trick instead of a treat. His idea was to broadcast an adaptation of H.G. Wells’ novel The War of the Worlds to make it sound like a contemporary invasion of Earth by hostile Martians. What Welles did not anticipate, however, was that thousands – perhaps even millions – of listeners believed the broadcast was real, and they panicked.

The hour-long CBS radio program, with a cast of four including Welles, described strange meteorites landing in New Jersey that turned out to be rocket ships with evil Martians inside that used “Death-Rays” and poisonous gas to wipe out humans. Welles produced, directed, narrated and starred in the program. His bold idea – which confused and frightened many listeners – was to present the story as a rapid-fire series of news flashes describing the horrible events as they seemingly were happening.

The Halloween trick turned out to be on Welles, as he received a backlash of negative reaction to his radio “stunt” as the Federal Communications Commission and members of Congress grumbled about possible censure, official investigations, and potential restrictions on future radio programming. The 23-year-old Welles was bemused by the audience’s – or “dialers” as they were called at the time – response, and issued a statement expressing his “deep regret over any misapprehension which our broadcast created among listeners.”

However, he defiantly added:

“I am even the more bewildered over the misunderstanding in the light of an analysis of the broadcast itself,” pointing out there were four reasons no one should have thought the broadcast was a genuine crisis – including the fact that four times during the broadcast the audience was told the radio program was fiction. In fact, the fourth disclaimer came at the end of the program, when Welles himself addressed the audience directly, explaining that the show was a Halloween trick on them, just like “dressing up in a sheet, jumping out of a bush and saying ‘Boo!’”

In the end, Welles got the last laugh. The huge uproar over the show garnered such publicity that Welles gained a major sponsor, the Campbell Soup Company, and his The Mercury Theatre on the Air radio program was renamed The Campbell Playhouse. The notoriety of “The War of the Worlds” radio program catapulted Welles to fame and spurred his career forward – just three years later he released his first film, Citizen Kane, in which he not only starred but co-wrote, produced and directed. It is generally recognized as one of the greatest films ever made.

The following six newspaper articles report the furor over Welles’ Halloween stunt. Historians have questioned whether as many people panicked as was reported at the time, but there is no disputing that some audience members believed the program was genuine and were terrified. The first newspaper article is a news report of the radio program and how it frightened its audience, the next two articles are editorials, the fourth article is Welles’ own explanation and defense of his show, and the final two articles concern the call for an official investigation.

Here is a transcription of this article:

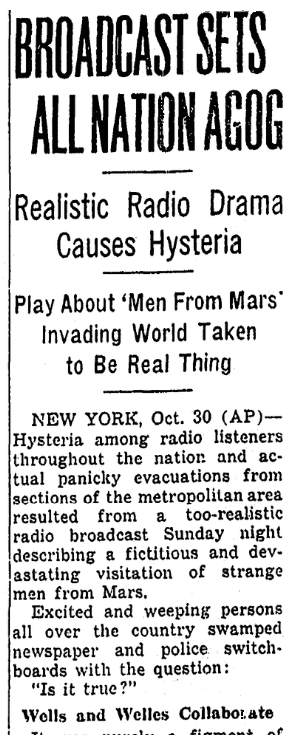

BROADCAST SETS ALL NATION AGOG

Realistic Radio Drama Causes Hysteria

Play about ‘Men from Mars’ Invading World Taken to Be Real Thing

NEW YORK, Oct. 30 (AP) – Hysteria among radio listeners throughout the nation and actual panicky evacuations from sections of the metropolitan area resulted from a too-realistic radio broadcast Sunday night describing a fictitious and devastating visitation of strange men from Mars.

Excited and weeping persons all over the country swamped newspaper and police switchboards with the question: “Is it true?”

Wells and Welles Collaborate

It was purely a figment of H. G. Wells’ imagination with some extra flourishes of radio dramatization by Orson Welles. It was broadcast by the Columbia Broadcasting System.

But the anxiety was immeasurable.

At Fayetteville, N.C., people with relatives in the section of New Jersey where the mythical visitation had its locale went to a newspaper office in tears, seeking information.

A message from Providence, R.I., said:

“Weeping and hysterical women swamped the switchboard of the Providence Journal for details of the massacre and destruction at New York and officials of the electric company received scores of calls urging them to turn off all lights so that the city would be safe from the enemy.”

Invading Hosts Envisioned

Mass hysteria mounted so high in some cases that people told police and newspapers they “saw” the invasion.

The Boston Globe told of one woman who “claimed she could ‘see the fire’” and said she and many others in her neighborhood were “getting out of here.”

Minneapolis and St. Paul police switchboards were deluged with calls from frightened people.

In Atlanta there was worry in some quarters that “the end of the word” had arrived.

Police Explode Myth

It finally got so bad in New Jersey that the state police put reassuring messages on the state teletype, instructing their officers what is was all about.

And all this despite the fact that the radio play was interrupted four times for the announcement: “This is purely a fictional play.”

Newspaper switchboard operators quit saying, “Hello.” They merely plugged in and said: “It’s just a radio show.”

The Times-Dispatch in Richmond, Va., reported some of their telephone calls came from people who said they were “praying.”

West Coast Interested

The Kansas City bureau of the Associated Press received queries on the “meteors” from Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, Beaumont, Tex., and St. Joseph, Mo., in addition to having its local switchboard flooded with calls.

One telephone informant said had had loaded all his children into his car, had filled it with gasoline, and was going somewhere.

“Where is safe?” he wanted to know.

Residents of Jersey City, N.J., telephoned their police frantically, asking where they could get gas masks. In both Jersey City and Newark, hundreds of citizens ran out into the streets.

Atlantans Hear of Planet

Atlanta reported that listeners throughout the southeast “had it that a planet struck in New Jersey, with monsters and almost everything, and anywhere from 40 to 7000 people reported killed.” Editors said responsible people, known to them, were among the anxious information seekers.

In Birmingham, Ala., people gathered in groups and prayed, and Memphis had its full quota of weeping women calling in to learn the facts.

Here is a transcription of this article:

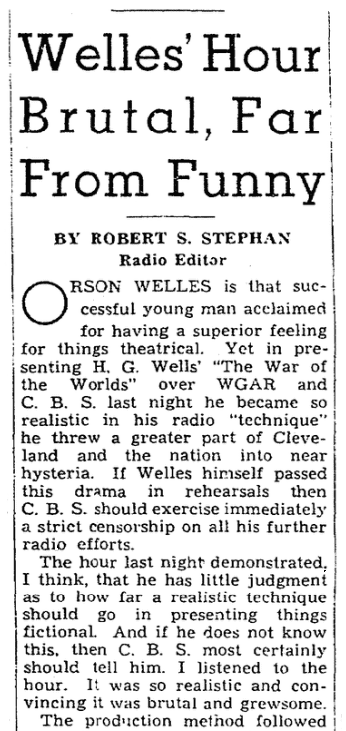

Welles’ Hour Brutal, Far from Funny

By Robert S. Stephan

Radio Editor

ORSON WELLES is that successful young man acclaimed for having a superior feeling for things theatrical. Yet in presenting H. G. Wells’ “The War of the Worlds” over WGAR and C.B.S. last night he became so realistic in his radio “technique” he threw a greater part of Cleveland and the nation into near hysteria. If Welles himself passed this drama in rehearsals then C.B.S. should exercise immediately a strict censorship on all his further radio efforts.

The hour last night demonstrated, I think, that he has little judgment as to how far a realistic technique should go in presenting things fictional. And if he does not know this, then C.B.S. most certainly should tell him. I listened to the hour. It was so realistic and convincing it was brutal and grewsome.

The production method followed the pattern networks use in broadcasting an actual new crisis. Names of real states and cities were in the script. Protests from dialers came over the wires during and after the drama. WGAR estimated it had more than 500 phone calls. Walter Winchell twice on his program advised there was no crisis in New Jersey. C.B.S. was on the air at least twice an hour or so after the drama to reassure dialers.

Young Mr. Welles ended his hour assuring dialers it was Halloween. Maybe so, Mr. Welles, but your dramatic prank was far from funny. In fact, it was about as funny as slipping a chair out from under some person who is just about to sit down. Well, some day, perhaps, radio will learn its lesson and cease to behave as an immature little boy behaves on “corn night.”

Here is a transcription of this article:

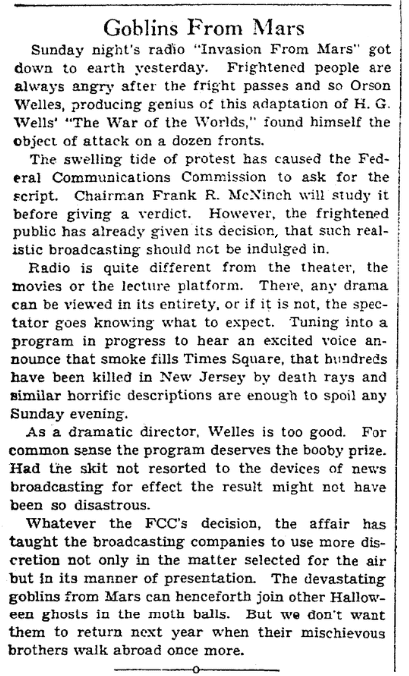

Goblins from Mars

Sunday night’s radio “Invasion from Mars” got down to earth yesterday. Frightened people are always angry after the fright passes and so Orson Welles, producing genius of this adaptation of H. G. Wells’ “The War of the Worlds,” found himself the object of attack on a dozen fronts.

The swelling tide of protest has caused the Federal Communications Commission to ask for the script. Chairman Frank R. McNinch will study it before giving a verdict. However, the frightened public has already given its decision, that such realistic broadcasting should not be indulged in.

Radio is quite different from the theater, the movies or the lecture platform. There, any drama can be viewed in its entirety, or if it is not, the spectator goes knowing what to expect. Tuning into a program in progress to hear an excited voice announce that smoke fills Times Square, that hundreds have been killed in New Jersey by death rays and similar horrific descriptions are enough to spoil any Sunday evening.

As a dramatic director, Welles is too good. For common sense the program deserves the booby prize. Had the skit not resorted to the devices of news broadcasting for effect the result might not have been so disastrous.

Whatever the FCC’s decision, the affair has taught the broadcasting companies to use more discretion not only in the matter selected for the air but in its manner of presentation. The devastating goblins from Mars can henceforth join other Halloween ghosts in the moth balls. But we don’t want them to return next year when their mischievous brothers walk abroad once more.

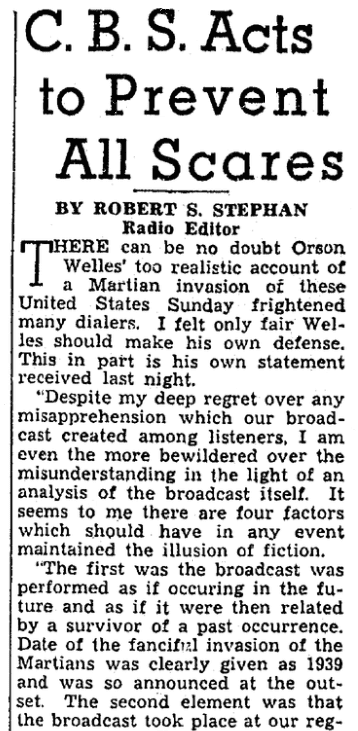

Here is a transcription of this article:

C.B.S. Acts to Prevent All Scares

By Robert S. Stephan

Radio Editor

There can be no doubt Orson Welles’ too realistic account of a Martian invasion of these United States Sunday frightened many dialers. I felt [it was] only fair Welles should make his own defense. This in part is his own statement received last night.

“Despite my deep regret over any misapprehension which our broadcast created among listeners, I am even the more bewildered over the misunderstanding in the light of an analysis of the broadcast itself. It seems to me there are four factors which should have in any event maintained the illusion of fiction.

“The first was the broadcast was performed as if occurring in the future and as if it were then related by a survivor of a past occurrence. Date of the fanciful invasion of the Martians was clearly given as 1939 and was so announced at the outset. The second element was that the broadcast took place at our regular Mercury Theater period and had been so announced.

“A third element was that at the outset and twice during this drama’s enactment listeners were told this was a play. At the conclusion a detailed statement to this effect was made. The fourth factor seems to me to have been the most pertinent of all, that is the familiarity of the fable. For many decades the ‘Man from Mars’ has been almost a synonym for fantasy.”

W. B. Lewis, C.B.S. vice president in charge of programs, sends me word: “It won’t happen again.” Says Lewis in part: “In order [that] this type of production will not happen again, the program department hereafter will not use the technique of a simulated news broadcast within a dramatization when circumstances of the broadcast could cause immediate alarm to numbers of listeners.”

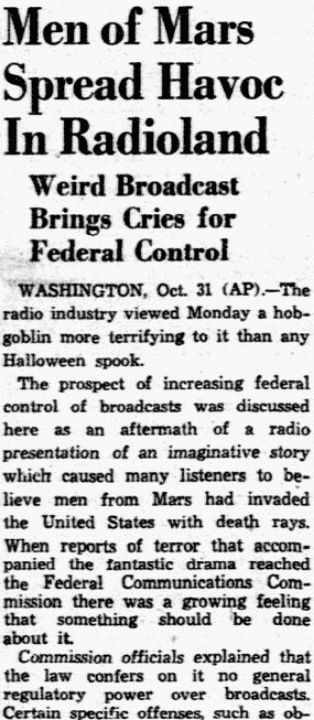

Here is a transcription of this article:

Men of Mars Spread Havoc in Radioland

Weird Broadcast Brings Cries for Federal Control

WASHINGTON, Oct. 31 (AP) – The radio industry viewed Monday a hobgoblin more terrifying to it than any Halloween spook.

The prospect of increasing federal control of broadcasts was discussed here as an aftermath of a radio presentation of an imaginative story which caused many listeners to believe men from Mars had invaded the United States with death rays. When reports of terror that accompanied the fantastic drama reached the Federal Communications Commission there was a growing feeling that something should be done about it.

Commission officials explained that the law confers on it no general regulatory power over broadcasts. Certain specific offenses, such as obscenity, are forbidden, and the Commission has the right to refuse license renewal to any station which has not been operating in the public interest. All station licenses must be renewed every six months.

Within the Commission there has developed strong opposition to using the public-interest clause to impose restrictions on programs. Commissioner T. A. M. Craven has been particularly outspoken against anything resembling censorship and he repeated his warning that the Commission should make no attempt at censoring what shall not be said over the radio.

Transcription Ordered

“The public does not want a spineless radio,” he said.

Commissioner George Henry Payne recalled that last November he had protested against broadcasts that produced terror and nightmares among children and said that for two years he had urged that there be a standard of broadcasts.

Saying that radio is an entirely different medium from the theater or lecture platform, Payne added: “People who have material broadcast into their homes without warnings have a right to protection. Too many broadcasters insisted they could broadcast anything they liked, contending they were protected by the prohibition of censorship. Certainly when people are injured morally, physically, spiritually and psychically, they have just as much right to complain as if the laws against obscenity and indecency were violated.”

The Commission called on Columbia Broadcasting System, which presented the fantasy, to submit a transcript and electrical recording of it. None of the commissioners who could be reached for comment had heard the program.

The other commissioners were silent or guarded in their comments, but a number of them indicated some steps should be taken to guard against a repetition of such incidents.

Won’t Happen Again

The broadcasters themselves were quick to give assurances that the technique used in the program would not be repeated. Orson Welles, who adapted The War of the Worlds, expressed his regrets. The Columbia Network called attention to the fact that on Sunday night it assured its listeners the story was wholly imaginary, and W. B. Lewis, its vice-president in charge of programs, said: “In order that this may not happen again, the program department hereafter will not use the technique of a simulated news broadcast within a dramatization when the circumstances of the broadcast could cause immediate alarm to numbers of listeners.”

The National Association of Broadcasters, through its president, Neville Miller, expressed regret for the misinterpretation of the program.

Senator to Act

Communications Commission Chairman Frank R. McNinch, declaring he would withhold judgment of the program until later, said: “The widespread public reaction to this broadcast, as indicated by the press, is another demonstration of the power and force of radio and points out again the serious public responsibility of those who are licensed to operate stations.”

Senator Clyde L. Herring (Dem.) of Iowa announced his intention of sponsoring a bill in the next Congress “controlling just such abuses as was heard over the radio last night.”

Despite the furor the broadcast created in the Commission, McNinch’s office reported only fifteen telegrams of protest had been received. Employees said, however, that they had received no letters yet and in program controversies in the past the protests had arrived by mail days later.

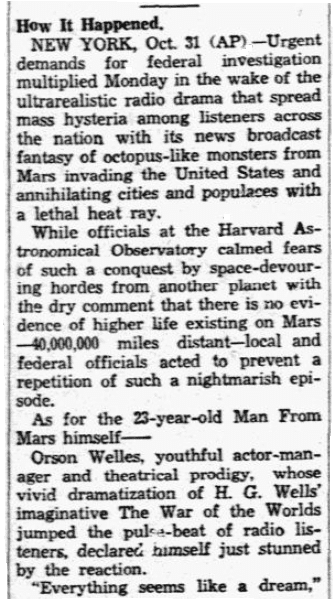

Here is a transcription of this article:

How It Happened.

NEW YORK, Oct. 31 (AP) – Urgent demands for federal investigation multiplied Monday in the wake of the ultra-realistic radio drama that spread mass hysteria among listeners across the nation with its news broadcast fantasy of octopus-like monsters from Mars invading the United States and annihilating cities and populaces with a lethal heat ray.

While officials at the Harvard Astronomical Observatory calmed fears of such a conquest by space-devouring hordes from another planet with the dry comment that there is no evidence of higher life existing on Mars – 40,000,000 miles distant – local and federal officials acted to prevent a repetition of such a nightmarish episode.

As for the 23-year-old Man from Mars himself –

Orson Welles, youthful actor-manager and theatrical prodigy, whose vivid dramatization of H. G. Wells’ imaginative The War of the Worlds jumped the pulse-beat of radio listeners, declared himself just stunned by the reaction.

“Everything seems like a dream,” he said.

Vied with McCarthy

Fresh reports from many sections of the country depicted the wave of terror unleashed by young Welles – whose weird, maniacal laughter was known to millions of radio listeners in his former role as The Shadow.

Unaware of the sensation he was creating, Welles played the part of a rapid-fire news announcer in the CBS drama which vied with the NBC Charlie McCarthy program on the air from 7 to 8 p.m. Sunday. Despite four distinct announcements that the broadcast was not genuine news, listeners who dialed in after the program started or merely caught a few stray lines of the drama were plunged into panic.

As Welles breathlessly described the fictional landing of the Martians near Grover’s Mills, N.J. (imaginary town), how they emerged from meteor space cars and sent waves of poisonous gas billowing in black waves over the countryside, gullible listeners became panic-stricken.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.