Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry gives more details about the remarkable story of Albert Cashier, a woman who fought 40 battles in the Civil War disguised as a man. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

Today I continue with the story of Albert D. J. Cashier (1843-1915), a Civil War Union Army soldier who served in Company G, 95th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, for three years. Cashier fought in 40 battles and earned the respect of his fellow soldiers, who never suspected Cashier’s secret: he was a she.

Cashier was a woman, born Jennie Irene Hodgers. Jennie was born in Clogherhead, Ireland, and came into this country as a stowaway young girl. When she enlisted in the Union Army on 6 August 1862, she did so under the name of Albert J. D. Cashier.

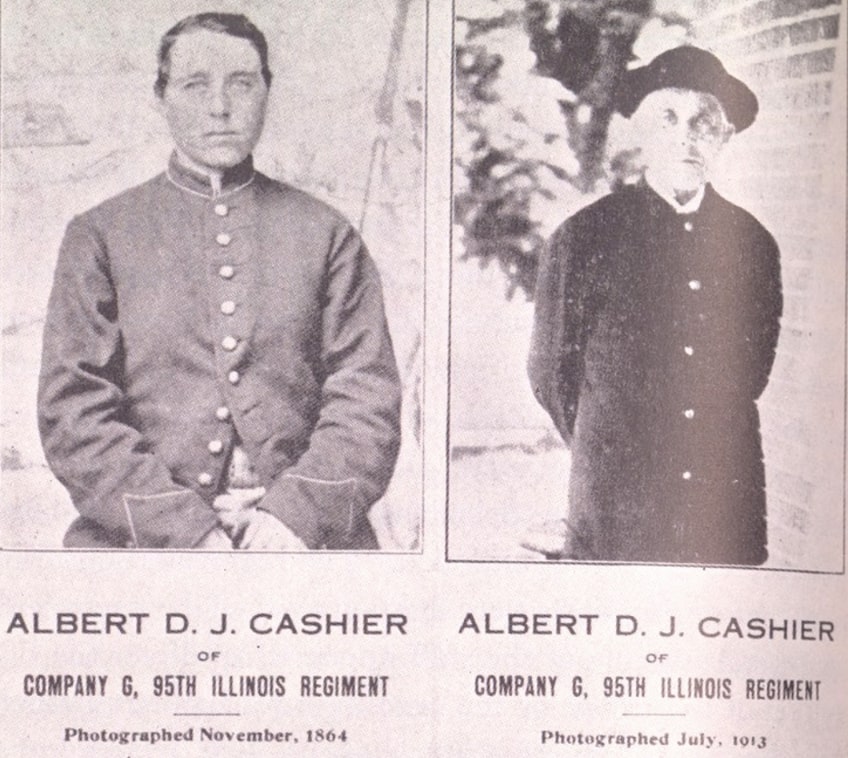

Long after the war, when Cashier’s pension was reviewed by the government, depositions from members of Company G, 95th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, were gathered. A double photo was used to determine Cashier’s identity. The men all confirmed the person in the two photos was Cashier, but they never knew they had been fighting alongside a woman.

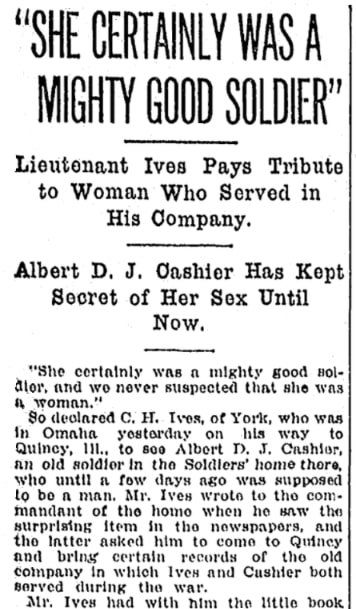

One of the veterans questioned during Cashier’s pension review was C. H. Ives, who had kept the individual records of Company G as orderly sergeant. When the news broke out that Cashier was a woman, Ives visited his fellow comrade in the Old Soldiers Home in Quincy, Illinois.

Ives shared some of his recollections with the Omaha World-Herald. His first claim: “She certainly was a mighty good soldier, and we never suspected that she was a woman.”

Here is more from Ives:

At Vicksburg on May 19, 1863, we had maintained so fierce a fire at Fort Hill that the enemy was driven from the guns and got out of sight behind their works. Cashier jumped up on a fallen tree and yelled at them, “Why don’t you get up, you darned rebs, where we can see you?” They were not more than a block distant, and could easily hear him. I was acting lieutenant at the time, and ordered him down. A storm of bullets swept across there, but he was not hit. Two days later I got a bullet that ended my active service…

Cashier went clear through, serving three years, and was mustered out with the regiment in 1865. He was in numerous battles, and I do not recall that he was wounded. I remember that on one occasion at Guntown, Miss., he was on picket duty all night. At that time the men were able to pick up contraband goods on the picket line, and frequently brought in stuff in jugs that caused some disturbance in camp. On this occasion, Cashier was seen by Colonel Dietzler, who was commanding the brigade, coming back into camp with a jug. The officer hailed him and demanded to know what he had in the jug. “Spring water,” was the reply. “Let me taste that spring water,” said the colonel, reaching for the jug. He tried it, and found that Cashier had actually found a spring and had managed to get a jug and was bringing some of it into camp. The brigade staff was standing near and had a quiet laugh at the colonel’s expense.

How a woman can serve years as a soldier in the field without any of her comrades finding it out I cannot understand. I know that I never suspected such a thing, or heard that anyone else did.

One sure thing. I never would make an affidavit that would deprive Cashier of a pension or anything else that is due a good soldier. She earned every bit of it. Her record would have been a creditable one for any man.

Even years later the legend of Cashier is still examined by historians and remains a topic of interest and intrigue today. In 1979 the Register Sun published a long account of her story, including firsthand testimonies from those who knew this mystery lady. Part of the article also covered many suppositions which grew about Albert/Jennie as the years went by.

This article reported:

Her entry into the war was probably not difficult. One recruit said: “They checked our hands and feet and counted our eyes,” an examination typical throughout history when an army faced a manpower shortage.

Harry Weaver, one of Jennie’s comrades, was called in by the federal pension bureau in 1914 for an affidavit, and he stated: “When we were examined at induction, we were not stripped. We never saw Cashier use the latrine. He was of very retiring disposition and did not take part in any games. He would sit around and watch, but would not take part. He had very small hands and feet. Smallest man in the company.”

After the war, the blue-clad solider from Company G… became a lamplighter, a sheepherder, a gardener, a thresher, and a janitor. One of her employers, State Sen. Ira Lish, built her a small home.

Goldie Ross, a former acquaintance, recalled that the quiet Jennie could “rock our baby daughter to sleep better than we could. He (most of Jennie’s acquaintances said it was hard to use the feminine pronoun with her) would go to town and buy her the most beautiful things. We wondered how he got such feminine tastes.

“But on Decoration Day,” Ross added, “he always led the parade, carrying the big flag, as slight as he was. He was in his glory then.”

…Likely to remain secrets are why she chose the name Cashier (some say it may be linked to the British term for military discharge pay), how it must have felt to vote before women were given that right, the emotions involved in fighting in 40 battles and skirmishes beside male soldiers, and the probable fear of discovery, says [historian Dr. Gerhart Clausius].

The Belvidere [Illinois] Civil War buff, author of several wartime subjects and past president of the Civil War Round Table, says he found the search of Jennie Hodgers’ history intriguing.

“I guess we can only conclude the truth is stranger than fiction.”

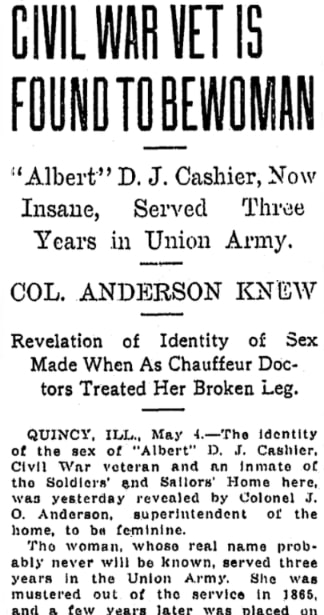

How Cashier’s secret was finally discovered is another facet of the sensational story. It made headlines all around the country in 1913, like this clip from the Times-Picayune.

A sober version of the story: Cashier worked as a driver for Illinois State Senator Ira M. Lish, and one day in 1910 the auto had mechanical troubles.

While Cashier was under the vehicle trying to find the problem, Lish accidentally rolled the car over Cashier’s leg, shattering it. When treating the fractured leg, a doctor discovered Cashier was a woman.

Cashier was admitted to the Illinois Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home. The doctor and Sen. Lish told Colonel J. Anderson, the home’s superintendent, about Cashier’s gender – and all parties agreed to keep it a secret and respect Cashier’s privacy.

Who leaked the story to the press I cannot tell you. Cashier developed dementia and was placed in the Watertown State Hospital for the Insane in East Moline, Illinois, in 1914, dying there on 15 October 1915.

In 1969 Mary Catherine Lannon published a dissertation on the subject. It is a great source for Cashier’s story, which you can view at Americana-Archives.com.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: gravestone for Albert D. J. Cashier at Sunny Slope Cemetery in Saunemin, Livingston County, Illinois. Cashier was buried with full military honors. Credit: Nancy, Doug, and Linda Bell of Illinois.

Related Articles: