Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry continues her series about women in colonial America who ran businesses and took out newspaper ads to promote them, with Part 2 of Mary Jackson and her son William’s story. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

During colonial America, women shopkeepers of all sorts were numerous in Boston, Massachusetts. One of the most interesting was Mary Jackson, “she merchant,” a popular “brazier” (seller of brass hardware), an important line of trade prior to the American Revolution. London products made her rich and popular, until British finery was boycotted. Her store and family reputation were later tarnished by scandal and misfortune.

After Mary formed a partnership with her son William, her shop – the Brazen Head – continued to prosper and grow. Although a devastating fire in 1760 set them back, they rose from the ashes and carried on selling everything from British hardware to linens.

However, another kind of flame ignited in Boston – which brought on the American Revolution, and the Jacksons were caught right in the crossfire.

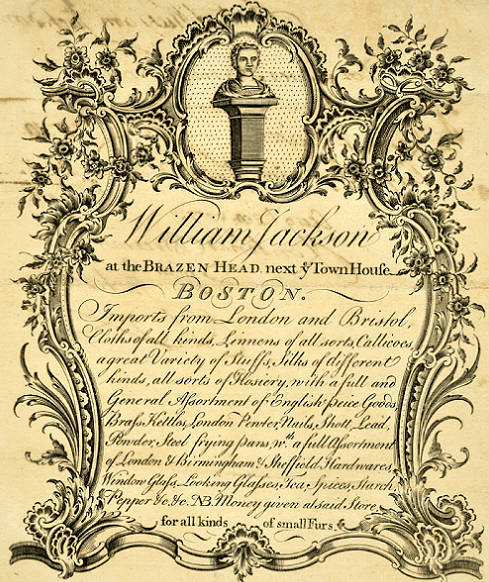

A rare and important pre-Revolutionary document in the collection of the American Antiquarian Society is William Jackson’s trade card, engraved by patriot Paul Revere in 1769.

The Jacksons believed politics did not belong in business, and they aggressively advertised their British goods in the newspapers from 1760-1770. This made much controversy and fired up drama.

The Townshend Acts of 1767 and 1768 raised revenue for the British Crown by imposing duties on goods imported to the American colonies. In protest, many merchants signed onto an agreement to boycott British goods – but not Mary and William Jackson, who were loyal to the Crown.

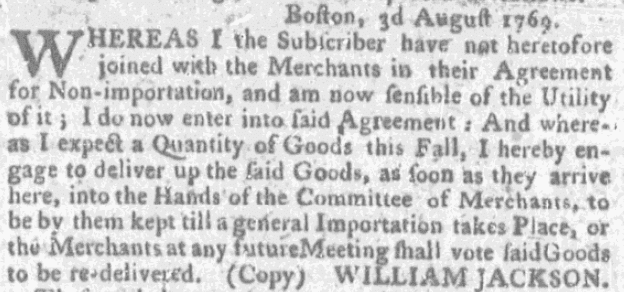

As public pressure grew, William eventually signed the patriotic merchants’ agreement on 3 August 1769, declaring:

“Whereas I the Subscriber have not heretofore joined with the Merchants in their Agreement for Non-importation, and am now sensible of the Utility of it; I do now enter into said Agreement.”

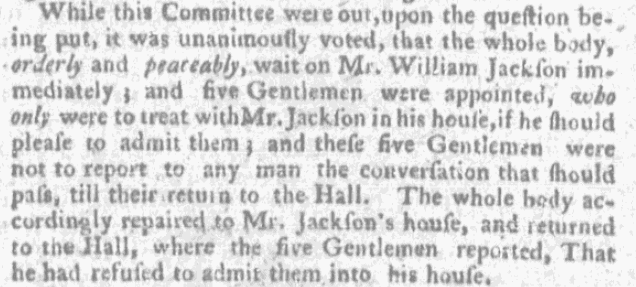

However, there was suspicion William was merely paying lip-service to the agreement, and a committee was sent to his house to discuss the matter. William refused to let them in.

Another hot bed topic: Mary rented rooms to British army officers. One tenant was Captain Thomas Preston, who commanded troops during the “Boston Massacre” of 5 March 1770. He was later tried for murder, but was defended by future president John Adams and acquitted. You can read more about this on the Library of Congress web page John Adams and the Boston Massacre of 1770.

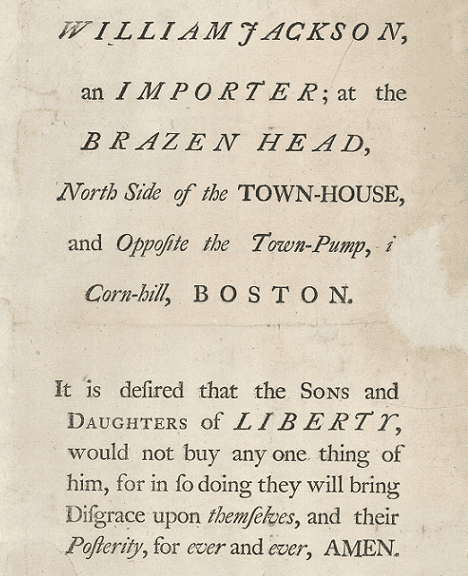

Anger against the Jacksons grew. In the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society (MHS) is a small handbill distributed in Boston throughout the winter of 1769-1770, declaring:

“It is desired that the SONS and DAUGHTERS of LIBERTY, would not buy any one thing of him [William Jackson], for in so doing they will bring Disgrace upon themselves, and their Posterity, for ever and ever, AMEN.”

William attempted to dodge the firebrands when the British forces evacuated Boston in March 1776. He purchased a large brig and tried to sail to safety, but was captured and thrown in the gaol. His capture was reported by the Boston Gazette, or, Country Journal:

“Last Wednesday Capt. Manley took and sent into Beverly, a large brig, after some resistance. This vessel [Elizabeth] was purchased by William Jackson, at the Brazen Head, who with… a number of others… were on board, besides a sergeant and 12 privates of the 4th or King’s own regiment, who are made prisoners.”

Another item in the MHS is a letter written by William to the Continental Congress on 6 July 1776. In the letter William complains of his imprisonment and requests that his confiscated property be returned. He was imprisoned for a year and went into exile in England after he was formerly banished by the Revolutionary government of Massachusetts in 1778.

William’s death was reported by the Boston Commercial Gazette:

“In England, Mr. William Jackson, [merchant] formerly of this town [aged] 79.”

What became of the Jacksons’ shop? Well, I found an ad in the Independent Chronicle dated 28 May 1778 in which William Scollay announced:

“Druggs and Medicines to be sold by William Scollay, at his Shop the Corner of State-Street, formerly called the Brazen Head.”

Mary died in 1780 and I found her obituary in the Boston Gazette dated November 13:

“Yesterday Morning departed this Life, in the 82d Year of her Age, Mrs. MARY JACKSON, Widow. Her Funeral will be from the House of her Son Mr. JAMES JACKSON in Union-Street, on Wednesday next at Three o’Clock in the Afternoon, if Fair Weather; where her Friends and Acquaintance are requested to attend.”

The Jackson line was not all lost to the Brits. James Jr. married Sara Rand, daughter of shop keeper William Rand. The couple ran their own enterprise in Boston and had a son James. That story will be for another day.

Note: Just as an online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, told Mary Jackson and her son William’s story in colonial America, they can tell you stories about your ancestors that can’t be found anywhere else. Come look today and see what you can discover!

Further Reading:

- Boston 1775 blog, J. L. Bell. “Captain Preston and the Boston Committee”

- Boston 1775 blog, J. L. Bell. “To be sold by Wholesale and Retail, By James Jackson”

- Dexter, Elizabeth Anthony Williams. “Colonial Women of Affairs: A Study of Women in Business and the Professions in America Before 1776.” University of California, 1924.

- American Revolution Podcast

Related Articles:

Thank you for posting a very interesting story of loyalist merchants, and what makes it particularly interesting is a woman colonial merchant.

Thanks Jeffrey. I have enjoyed working on the colonial dames business activities. I am amazed at the amount of ads and information I found on GenealogyBank! Stay tuned!

Melissa, Great series of articles! Keep them coming.

Thanks Elizabeth! Stay tuned; I am working on lady healers and they are competing aggressively among both genders. Those midwives took the men for a run for their money!