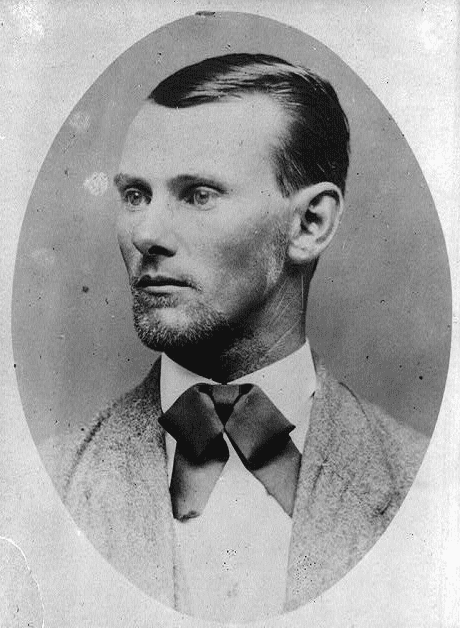

Jesse James is one of the most colorful, controversial, and enduring figures in American history. Was he a loyal Confederate soldier who refused to surrender, continuing to defend his hard-working Missouri compatriots after the Civil War from marauding carpet-baggers and Northern humiliations, a nineteenth-century Robin Hood who robbed only the rich and supported the poor? Or was he a cruel, bloodthirsty guerrilla during the war who went on killing and plundering after the rest of Missouri was willing to accept peace and the war’s end?

From 1868 until the disastrous Northfield, Minnesota, bank robbery on 7 September 1876 that broke up the gang, Jesse James rode with a group of former Confederate guerrillas that came to be known as the James-Younger Gang, whose core members were brothers: Frank and Jesse James; and Bob, Cole, Jim and John Younger.

The exploits of Jesse James were often glorified in the pages of the Kansas City Times, whose founder and editor, John Newman Edwards, was a former Confederate cavalryman. An editor who worked with Edwards witnessed a remarkable late-night encounter with the James-Younger Gang and wrote a detailed account of their meeting, along with descriptions of some of the early members of the gang.

Here is a transcription of this article:

THE CHIVALRY OF CRIME.

A Kansas City Ex-Editor’s Reminiscences of the Gadshill Train Robbers.

Personnel of the Party – Arthur McCoy – John and Cole Younger – The James Brothers – Will. Shepherd.

[Cor. Washington Capital.]

Agreeably to your request I give you some sketches of the notorious band of Missouri highwaymen, whose latest exploit, the robbing of the train on the Iron Mountain road, is the sensation of the hour. I go of course on the presumption of the telegraphic dispatches that the perpetrators of the robbery were Arthur McCoy, the Younger Brothers, the James boys and Will Shepherd. If this presumption is mistaken, I hope these young gentlemen of the highway will pardon me, but it must be said that there is nothing in their records at least that would tend to throw doubt upon the assumption of the telegraphic dispatches to the press. My knowledge of the boys dates from the time when I was associated with John C. Moore and John N. Edwards, conducting the Kansas City Times. The boys had been Confederate soldiers, serving part of the time with Shelby and Marmaduke, and Moore and Edwards had been some time their commanders, and had also been, before the boys became outlaws, their associates and friends. Thus I learned much of their personal history, whenever their exploits made them the theme of conversation in the Times office, which, by the way, was quite frequent.

Arthur McCoy, who may be said to be the executive officer of the band, is a remarkable man, with a somewhat remarkable history. Before the war he was a resident of St. Louis, where he occupied a respected position in society for some time, but which he partially lost by his reckless behavior during the two or three years immediately preceding the outbreak of the conflict. At this time he joined one of the fire companies of St. Louis, and his combative propensities soon gave him unenviable notoriety. He was probably the worst customer to fool with that run with the “masheen” in St. Louis at that time, which is saying as much for his fighting capacity as can be put in so few words. McCoy is about five feet eleven inches high, dark complexion, had dark-brown hair and dark hazel eyes, a well-proportioned and altogether handsome face, and weighs, I should suppose, about 175 pounds. He is well educated – that is, has a good common education – and is a man of considerably more than average intelligence. During the war he did a good deal of service as a spy, and this was the school from which he graduated the desperado that he is. I have not time or space to record any of his adventures as a Confederate spy, but those who know what sort of warfare was waged west of the Mississippi, know that the part he played often involved desperate work, and there are several instances which go to show that none of it was ever too desperate for him. McCoy has one of those peculiar organisms whose possessors seem to deserve no credit for their courage. His bravery, which is absolute, is a sort of second nature; the result, not of pride or the fear of being called a coward, but of a fierce insensibility to danger, and a total recklessness of personal hazard that gives him nerve under all circumstances. His hand goes to his revolver-butt or his knife-hilt by an instinct as tiger-like as the aim of his bullet is infallible or the thrust of his Bowie decisive.

I don’t suppose McCoy ever shot at a man whom he did not hit, nor that he was ever in a situation where his judgment was not as clear as his impulses were sudden and deadly. I don’t know how he will die, but I suppose as he has lived, violently, though I will venture to assert that when he does lie down with his boots on forever, those who brought him down will not soon forget the circumstances, unless they should forget it immediately by keeping him company. I don’t know how many thousand dollars in rewards are set on the head of Arthur McCoy, but it amounts to considerably more than the year’s salary of a cabinet officer – quite a snug little fortune. Though avaricious as I am, I haven’t the remotest idea of attempting to make money by earning those rewards. As between the two I think I would prefer to undertake to earn the same sum by swimming over Niagara falls. Moreover, most men who know McCoy are in the same fix that I am.

Of the two Younger boys, John and Cole, I know but little, having never seen but one of them, and him only for a few minutes, one night in Kansas City. Then he was on horseback, all muffled up, so that I could not see his face. But my memory of his conversation is that he was a pleasant-voiced fellow of a rather jovial turn of mind, a rather rapid talker, and capable of saying good things. At all events, I remember one of his observations, which was that he didn’t ask any odds of society, but thought it was unjust of the newspapers to rate him with ordinary thieves. He said he supposed his fame would be handed down to posterity, and all he wanted was a fair show, and not to be classified with pickpockets and sneak-thieves. He said he never broke into anybody’s house, nor picked up any valuables he found lying around loose.

When he wanted to make war upon society he went out on the highway, where every man had the same show. This was a short time after he and Shepherd, and either his brother or McCoy, probably the latter, had ridden up to the ticket-office of the Kansas City exposition grounds and robbed the gatekeeper, Ben. Wallace, in broad daylight, and in the face of ten thousand people. If anybody wants to know why I did not give the alarm and have this outlaw captured or killed – as the scene of this episode was on Delaware street in Kansas City, within twenty rods of the police-station – I will say that I had some affairs which required settling up, and besides was not on as good terms with the Almighty as I should like to be before undertaking such a feat as that. I knew that underneath the heavy cape that fell down over his shoulders till it touched his horse’s back, was a belt studded about with four dragoon pistols, which, in the hands of Cole Younger, were equivalent to twenty-four dead men, if anything should impel him to set them agoing. So I refrained, as I presume any other law-abiding citizen of ordinary sense would have done, under the circumstances. The two Youngers belong in Cass county, where they are very respectably connected, their career bringing sorrow and humiliation to several most estimable families.

I know nothing of Will Shepherd or his antecedents, beyond that he belongs in Jackson county, his home, I believe, being near old Fort Osage. He was in the Confederate army, though in what command I am not able to say, but I think he was with Quantrill at Lawrence. He is not as remarkable in person or mind as the rest of his associates, though undoubtedly their peer in recklessness and desperateness.

The James brothers, Jesse and Frank, are the ornaments of the party. Jesse, the elder, is the administrative leader of the gang. He manages its finances, carries on its diplomacy and devises its strategy. He is altogether a paradoxical fellow. Outside of journalism or the learned professions there is not a better writer nor a more fluent talker than Jesse James in the trans-Mississippi country that I know of. He is about five feet nine in height, slenderly built, of a florid complexion, reddish-brown hair, blueish-gray eyes and has rather sharply-defined features. His home, or rather his mother’s residence, is near Kearney station, in Clay county, and his family is one of the most respected in west Missouri. His uncle, Mr. T. M. James, is a wholesale merchant of Kansas City and one of its most substantial citizens. I have no idea what made Jesse James the terrible desperado and outlaw that he is. There is nothing essentially savage in his nature, and on the other hand he is a generous, good-hearted fellow. In the time when he was a member of society, and before every man’s hand had been raised against him and his against every man in retaliation, he was as genial and inoffensive a young man as there was to be found, and one who gave as good promise of a useful career. But he has become a terror and a scourge, and seems all the more dangerous by reason of the intellect that ought to have fitted him to adorn rather than curse his generation.

When I was in the Kansas City Times office as its associate editor, during the campaign of 1872, I used frequently to receive communications from Jesse James on various subjects of public interest, which were always unexceptionable in tone and expressive in sentiment, and which always found place, anonymous of course, in the columns of the Times.

One night about 11 o’clock, in the fall of 1872, Maj. Edwards and I were sitting in the editorial rooms of the Times discussing various matters, when the door opened and a man entered the room. He was muffled up to the eyes, and as he came in he gave a quick glance around to see how the land lay. He then said: “There are some gentlemen outside who wish to see you. They are on horseback and do not want to dismount.” The man who came in was Arthur McCoy. The men on horseback in the street were Jesse and Frank James and Cole Younger. Now, about a week or two before that the Kansas City Sunday Times had printed an editorial in which, while the crimes of these men had been denounced, their sublimated hardihood had been commented on admiringly. They had come to thank us for our appreciation of their pluck and daring. As a slight testimonial the boys had brought along a magnificent gold watch and chain which they desired to present to the writer of the article, or the editor of the paper, Jesse James observing that he had a presentation speech prepared, which might be reported in short-hand and the whole affair published in the morning paper. The proffered testimonial was, of course, declined on the ground that the owner might recognize the watch and make trouble. At this Jesse became indignant, and declared that he hoped we had a better opinion of him than to suppose that he would present to us a watch of which he had despoiled some one else. He had bought that watch, and not only that, but had come honestly by the money he bought it with. However, the testimonial was respectfully but firmly declined.

“Well, then,” said Cole Younger, “what can we do to testify our gratitude?”

“Is there anybody you want killed?” mildly inquired Frank James. “If there is, just name him, and we’ll bring you his scalp at this hour tomorrow night, if he is within twelve hours’ ride.”

This kind offer was also politely declined, as we thought we could get along just as well with our enemies alive as with them dead, and no doubt a good deal better, since it is an important element of success to have enemies.

“Have any more rewards been offered for our capture?” inquired McCoy, as they turned their horses’ heads to go.

“If you see anybody who wants to earn the price already set on our heads,” interrupted Jesse James, “tell them they will find us somewhere in Fort Osage township or down in the Sni hills. We shall be glad to see them.”

“And we will promise them a warm reception,” said little Frank James in a demure way. “If they come, they won’t be likely to forget our hospitality very soon.”

“I don’t reckon it would be worthwhile for anybody to come after us,” chimed in Cole Younger; “the rewards are only a little over $20,000, and that would hardly pay funeral expenses by the time they got all of us.”

Then the boys all laughed at the savage wit of Cole, who is the wag of the party, and they spurred their horses and rode away into the night and back to their wild haunts and their strange desperate life. I might give other anecdotes, but this sketch is already too long. People may wonder at what I have said, and ask why we did not try to entrap these men and surrender them to justice. Well, I will answer that question with another. On the heads of the four desperadoes that visited us that night were rewards aggregating, I believe, $21,000. Why did not other law-abiding citizens try to capture them? The question answers itself. No man or posse of men will ever take Arthur McCoy, or the James boys, or the Youngers, or Wm. Shepherd, alive.

The rewards offered, so far as known, for the Gadshill robbers is $10,000 by Gov. Woodson, $5,000 by the general post office department, and $2,500 by Gov. Baxter, of Arkansas.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Are there any outlaws in your family tree? Please share your stories with us in the comments section below.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Related Articles: