Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry tells the bizarre story of an American who began digging up a graveyard in England in 1923 looking for the bones of Pocahontas. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

In 1923 the village of Gravesend, England, was in an uproar when Chicago archeologist Edward Page Gaston began unearthing hundreds of graves to find the remains of the Indian Princess Pocahontas, wife of John Rolfe of Jamestown, Virginia, who was buried at the parish church on 21 March 1617.

It is important to note that after the original church burned in 1727, many of the bodies buried there, including that of Pocahontas (in an isolated tomb), were put in a common grave in the church yard.

It was not the first time the remains of Pocahontas had been in the news. I found a 1907 newspaper clip from the Baltimore American that claimed the skeleton of Pocahontas was discovered by workmen excavating at Gravesend. Experts said they had no doubt it was the skeleton of the Indian girl.

There were discussions about sending the remains back to Jamestown for the Tri-centennial exposition, but that never came to fruition. One can only assume that if these really were the bones of Pocahontas, they were once again laid in Gravesend churchyard.

The 1923 story of Gaston and his big dig made headlines across the globe.

The photo caption for this picture read:

“Edward Page Gaston with Canon Gedge, blind rector of the St. George’s Church in Gravesend along with others. Gaston is turning over the first soil in the search for the bones of Pocahontas.”

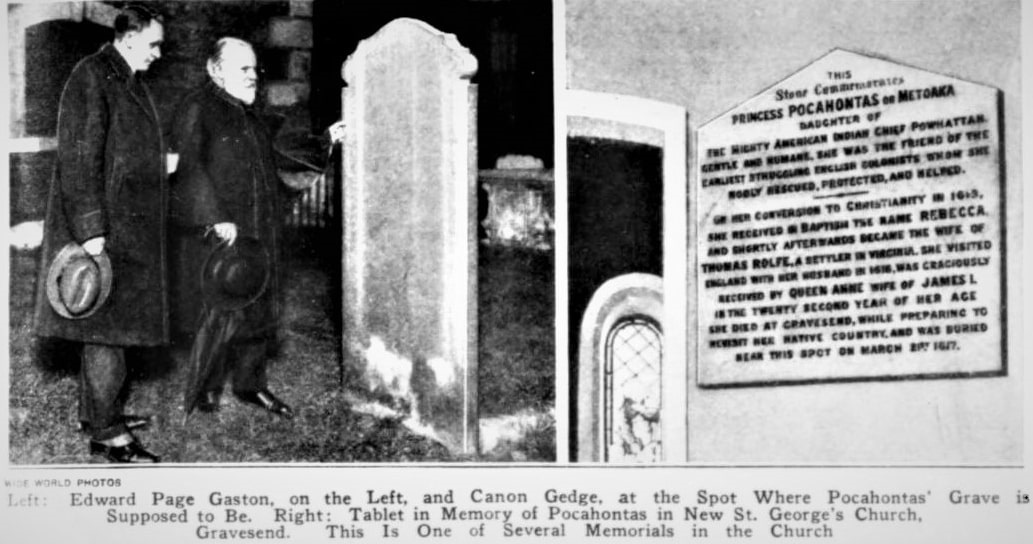

Here is another photo of Gaston and Gedge.

The inscription on the stone tablet reads:

This stone commemorates Princess Pocahontas or Metoaka, daughter of the mighty American Indian Chief Powhattan. Gentle and humane, she was the friend of the earliest struggling English colonists whom she nobly rescued, protected, and helped.

On her conversion to Christianity in 1613, she received in baptism the name Rebecca, and shortly afterwards became the wife of Thomas Rolfe, a settler in Virginia. She visited England with her husband in 1616, was graciously received by Queen Anne, wife of James I.

In the twenty-second year of her age she died at Gravesend, while preparing to revisit her native country, and was buried near this spot on March 21, 1617.

Not only was Gaston disturbing and disrespecting the dead, but he was insisting that it was his birthright because he claimed to be a direct descendant of Pocahontas. As such, he said it was his duty to return her to America.

That was a lie: Gaston does not have this lineage.

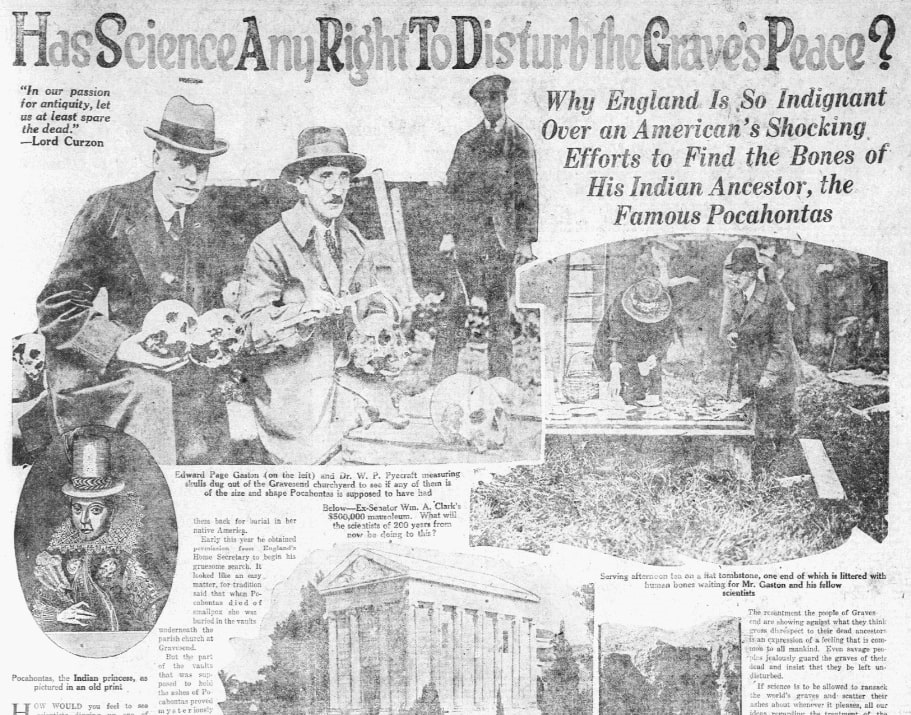

Here is an article published in the Dallas Morning News.

This article reported:

No, this ransacking of the graveyard which is filling the people of Gravesend with horror and indignation and arousing a storm of protest all through England is merely to satisfy the interest of Edward [Page] Gaston, an American archaeologist, who happens to be a descendant of Pocahontas.

…Early this year he [Gaston] obtained permission from England’s Home Secretary [William Clive Bridgeman, 1st Viscount Bridgeman] to begin his gruesome search. It looked like an easy matter, for tradition said that when Pocahontas died of smallpox, she was buried in the vaults underneath the parish church at Gravesend.

But the part of the vaults that was supposed to hold the ashes of Pocahontas proved mysteriously empty, and then the search was continued in the churchyard outside.

Soon the villagers of Gravesend were shocked to see a large force of men at work with picks and shovels in the burial place where so many of their ancestors rested and which they have always held in such reverence.

Under the direction of Mr. Gaston and his English associates, Dr. W. P. Pyecraft [William Plane Pyecraft], assistant keeper of osteological collections in the British Museum, and Sir Arthur Keith, of the Royal College of Surgeons, the laborers were bringing to the surface great quantities of human bones. The skulls and other parts of skeletons were heaped up all over the cemetery for Mr. Gaston and his fellow scientists to sort over and measure.

What particularly shocked the people of Gravesend was to see the excavators partaking of afternoon tea on a flat tombstone piled high at one end with bones. Meanwhile the workmen, with cigarettes in their mouths, were hauling up more and more of the cemetery’s contents and photographers were busy making snapshots of the ghastly scene.

The fact that the excavators have the decency to re-bury with proper religious ceremonies the bones they found of no interest to them has failed to check Gravesend’s indignation. The blind rector [Rev. Canon Gedge] of the parish church is being bitterly denounced because he permitted the excavations, and also because he officiated at the re-interment of the bones.

The popular indignation soon boiled over the limits of Gravesend and heated up all of England.

Marquis Curzon, the Foreign Secretary, addressing a meeting of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, said “Let us at least spare the dead.” He denounced the destruction of works of art in the past and asserted that reverence for ancient buildings was an admirable sentiment.

He said that it was indeed almost a religious cult, and added:

“But there is one form this cult takes which seems to me to be antiquarianism run mad – the modern craze for taking up the remains of the dead.”

To be continued…

Further Reading: In 2000 there was another project launched to recover the remains of the Indian Princess. You can read about it in the Los Angeles Times: “A Quest by a Dream Team to Bring Pocahontas Home.”

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in.

Note on the header image: a portrait of Pocahontas engraved by Simon van de Passe in 1616. It is the only known representation of her made during her lifetime. Credit: National Portrait Gallery; Wikimedia Commons.

Related Articles:

I’ve always been fascinated with Pocahontas so this was a real pleasure to read. Great article and can’t wait to read your next!

Thank you! I am glad you enjoyed it and I so appreciate the feedback!

That’s awful, digging up and disturbing all those graves. Leave the dead alone. I can see why God personally buried Moses in an unmarked grave!!