Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry writes more about the Salem witch trials of 1692, focusing on objects from that time preserved to this day. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

Today I continue with my coverage of the relics at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) featured in the Salem Witch Trials: Restoring Justice exhibition gallery running through November 26.

To recap: My last story featured the needlework sampler made by Mary (Hollingsworth) English, wife of wealthy merchant Philip (or Phillip) English.

Both Mary and Philip were arrested for witchcraft in 1692. To view the files online, visit historian Margo Burn’s site A Guide to the Primary Resources of the Salem Witchcraft Trials.

The historical accounts of the English family’s tribulation are furnished in the diaries of Dr. William Bentley (1759-1819).

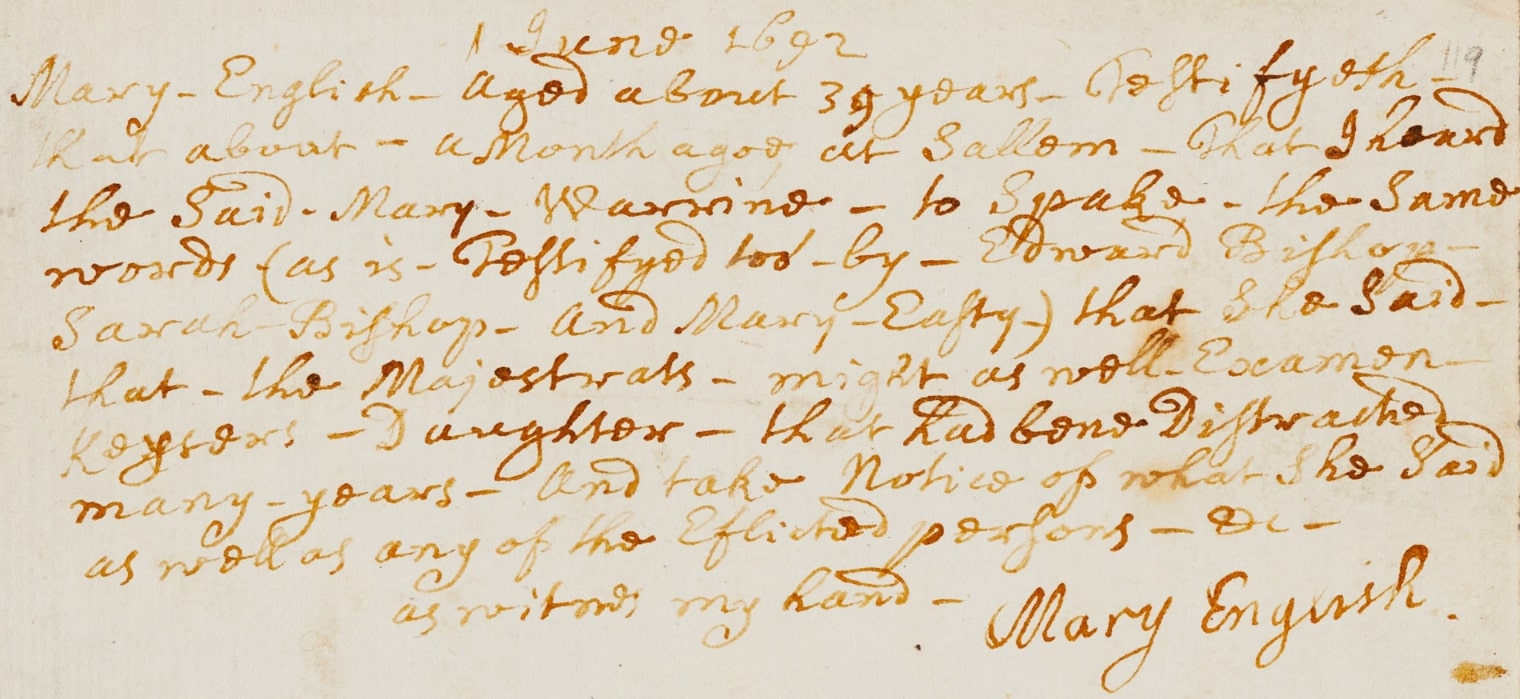

Mary English presented testimony on 1 June 1692 against her accuser Mary Warren, the servant of John and Elizabeth Proctor. That document still exists. It is possible English wrote and signed this document with her own hand, a rare act for a 17th-century woman.

Why Mary and Philip were targeted may have been as simple as jealousy, as they were considered two of the richest residents in Salem. Incidentally, Philip English had been made a constable in March of 1692, and that gave his enemies even more reason to envy and resent his fortunate lot in life.

In their book Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft, Boyer and Nissenbaum asset that:

“If one had to choose the single person most representative of the economic and social transformations which were overtaking Salem and Massachusetts as a whole in the late seventeenth century, Philip English might as well be that person.”

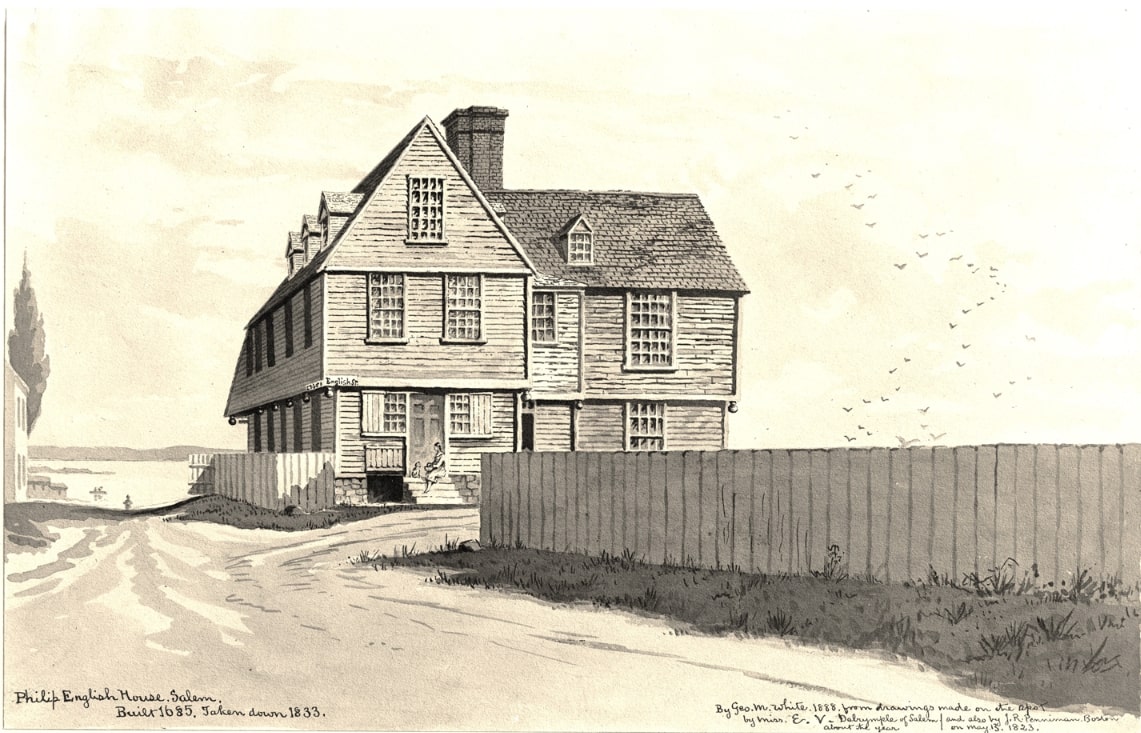

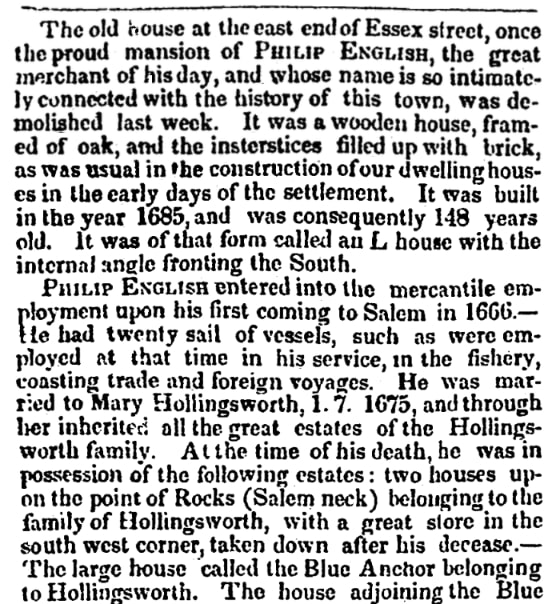

When the large mansion owned by Philip English was torn down in 1833 the Nantucket Inquirer covered the story, giving details of the worth and vast property holdings held by the prosperous merchant.

Among the valuable assets listed: 20 ships, three stores and a wharf, plus the various buildings acquired by himself or inherited from the Hollingsworth family through his marriage to Mary, which according to this article included the following:

…two houses upon the Point of Rocks (Salem Neck) belonging to the family of Hollingsworth, with a great store in the southwest corner, taken down after his decease. The large house called the Blue Anchor [Tavern] belonging to Hollingsworth. The house adjoining the Blue Anchor called Allen’s. The mansion house on land of Hollingsworth, opposite Turner’s and Becket’s Street. A house bounded on the above called Gale’s. Two houses on the corner going to the bridge, on the left. A house opposite the eastern end of Daniel’s Street. A house where St. Peter’s Church now stands, taken down when Mr. English gave the land upon which the church was erected, for that purpose. A house where the Hathorne’s lately lived, corner of Essex and Cambridge Streets.

After their arrest, Philip and Mary English were taken to a Boston jail because the Salem jail was too crowded. Now, how events unfolded after the Englishes were housed in the Boston jail is not certain, but they escaped and made their way to New York, where they took refuge in the home of Benjamin Fletcher, colonial governor of New York.

Accounts vary, but it is believed they escaped Boston with the assistance of Rev. Joshua Moody who, sources say, wrote in the text of his sermon: “If they persecute ye in one city flee to another.”

Benjamin Frederick Browne (a direct descendant of Philip through his daughter Mary English, who married William Browne) believed Philip rode his horse with the horseshoes reversed to avoid detection when he escaped.

Browne was a good friend of Nathaniel Hawthorne, whose stake in the story comes through family marriages. Part one of this story covered the Crowninshield connection – that branch furnished information for Dr. William Bentley’s diary. And some of the Browne family is connected to the House of Seven Gables.

Philip’s other daughter, Susannah English, married John Touzel. They had a daughter Susannah who married John Hathorne, grandson of John Hathorne, one of the leading judges of the Salem witchcraft trials. (See: Phillips Library, PEM, English/Touzel/Hathorne Papers, 1661-1851 MSS 11.)

Susannah and John Hathorne had a daughter, also named Susannah, who married Samuel Ingersoll. They in turn had a daughter, also named Suzannah (“Dutchess,” 1784-1858), who never married and was the former owner of the House of Seven Gables. She and other family members were sources for Dr. Bentley’s diary. Suzannah is the 4th lineal descendant of Philip and Mary English.

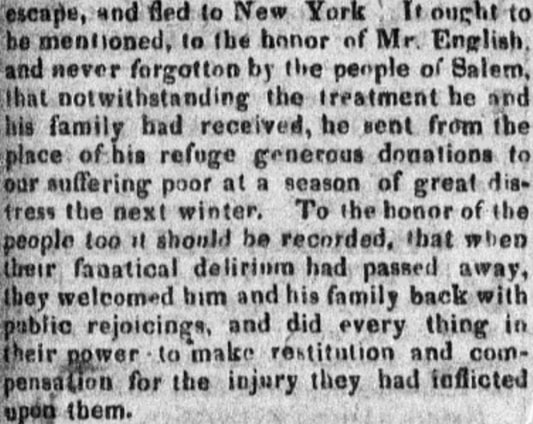

In 1831 the Portsmouth Journal noted that the English family eventually returned to Salem from their refuge in New York, only to find their home plundered. The town would begin to mend the wrongs; however, the process took many years.

This article reported:

It ought to be mentioned, to the honor of Mr. English, and never forgotten by the people of Salem, that notwithstanding the treatment he and his family had received, he sent from the place of his refuge generous donations to our suffering poor at a season of great distress the next winter. To the honor of the people too it should be recorded, that when their fanatical delirium had passed away, they welcomed him and his family back with public rejoicings, and did everything in their power to make restitution and compensation for the injury they had inflicted upon them.

According to Henry W. Belknap in Philip English the Commerce Builder, the English family received some compensation for the substantial losses incurred due to this dark tragedy.

It was not until 1711 that any attempt was made to reimburse those whose property had been confiscated – and then the Legislature set aside only £600 to cover everything! Philip English alone figured his losses at £1183.

Not all victims and the descendants of the witchcraft hysteria were easily appeased. It would take years for some to recover compensation or pardon. (See: “Witchcraft: Salem Witch Trials” Part One and Part Two.)

Stay tuned for more relics!

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: witchcraft trial at Salem Village. The central figure in this 1876 illustration of the courtroom is usually identified as Mary Walcott. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Related Articles: