Introduction: In this article, Gena Philibert-Ortega searches old newspapers to learn more about the Oatman family massacre and the subsequent Indian captivity of Olive Oatman. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

As the United States grew in the second half of the 19th century and pioneers answered the call to “go west,” stories of the successes and dangers of that journey were printed in newspapers across the country. People have always been either excited or afraid, or a combination of both, of the unknown—and the great unknown was what greeted those early pioneers. One of their fears was the possible danger that awaited them at the hands of the Native American peoples.

Some whites were taken prisoner during American Indian attacks on wagon trains, and the retelling and publishing of Indian captive stories was very popular with the public at that time. Stories like that of the Oatman family massacre—and, ultimately, the rescue of Indian captive Olive Oatman—helped feed the hatred and fear of the Native American population.

The Oatman Family Massacre

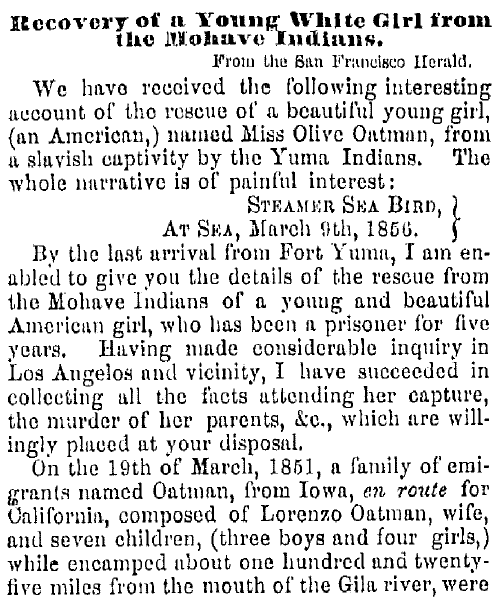

The Oatman family (parents Royse and Mary Ann Oatman, and their seven children) were part of a wagon train bound for the west in 1850. Eventually due to differences in opinion, they split from their group and were traveling on their own when some Apache (or perhaps Yavapai) Indians attacked them along the Gila River in present-day Arizona in February 1851. In this attack the entire family was killed except for sisters Olive (age 14) and Mary Ann (age 7), as well as their brother Lorenzo who was clubbed and left for dead, but recovered. Olive and Mary Ann were taken to live with their Indian captors. Just before the attack, Royse Oatman had sent a letter to Fort Yuma asking for assistance because he was sure that, without any help, he and his family would die.*

The Captivity of Olive and Mary Ann Oatman

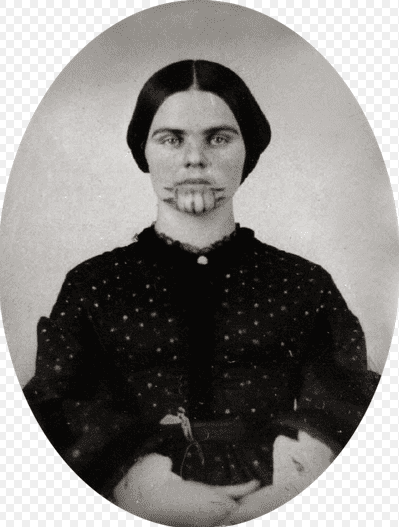

One year later the two sisters were traded to a group of Mohave Indians, who seemingly welcomed the girls into their tribe by giving them traditional blue chin tattoos. During their time with the Mohave, younger sister Mary Ann Oatman died of starvation during a drought. Finally, after a total of five years of Indian captivity, the army rescued Olive Oatman by exchanging some material goods for her in February 1856.** She was 19 years old.

This 1856 newspaper account summarizing her capture by the Native Americans and subsequent release is representative of news articles that appeared throughout the United States. Such newspaper articles must have served as fodder for people’s belief in the savage nature of the native peoples, and what may befall pioneers who crossed the trails heading west.

As time went on the story of Olive’s Indian captivity was immortalized in books and numerous newspaper articles. In some cases, men claiming to have been part of the rescue efforts also told their story. One such man, W. F. Drannon, is now known to have fabricated the tales he published in books and newspapers. His story of “rescuing” Olive included him single-handedly saving her. Even in our ancestors’ days there were those who wanted their 15 minutes of fame!

Like any story, some embellishments are bound to occur over time which can make for a murky recounting of historical events.

Interestingly enough, this old 1800s newspaper article—while telling about the Oatman massacre and captivity—also provides a nice genealogy that includes the name of Olive’s parents, where they were married, and their westward migration route. While the story of the killings and subsequent kidnapping of the girls is described, it is also reported that after the attack, Lorenzo happened upon a group of “friendly” Indians and they “humanely took him in their protection.”

Telling the Oatman’s Story

Like a modern-day expose snatched from the headlines, Olive’s story was quickly packaged into an 1857 book by Royal B. Stratton entitled Captivity of the Oatman Girls: Being an Interesting Narrative of Life among the Apache and Mohave Indians.

An 1857 newspaper article printed prior to the publication of the book seems to promise that it is a must-read: “…there is an abundance of material to render it a thrilling and interesting narrative.”

Olive took to the lecture circuit after the book’s release so that she could tell her story. This provided interested audiences the opportunity to hear her version of the events and gaze upon her tattooed chin, a curiosity among white Victorians. It also provided Olive with a way to secure funds for her education and living expenses. Her lecturing concluded once she married and settled in Texas, where she eventually died in 1903.

What parts of Olive’s story were fact melded into fiction or at the very least embellishment, may never all be sorted out. Many rumors and falsehoods were told about Olive, satisfying the public thirst for “celebrity” gossip much as is done today. While not the first woman to share her true story of being held captive by the Indians, Olive became well-known for her prominent facial tattoo which served as a constant reminder of the dangers of the western frontier.

Historical newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, are not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors—they also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Are there any Indian captive stories in your family history? Please share your stories with us in the comments.

Related Indian Captivity Articles:

- The Disappearance—and Mysterious Reappearance—of Matthew Brayton

- Find & Preserve Your Family’s Stories

- New Family Story Find: My 18th Century Uncle Jonathan Dore

___________

* Letter signed by Oatman to Brevet Major S.P. Heintzelman, February 15, 1851.

Transcript of letter. BANC MSS C-E 64:18. Images of Native American. Accessed 28 September 2014.

** Sherrie S. McLeRoy, “Fairchild, Olive Ann Oatman,” Handbook of Texas Online. http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/ffagr. Accessed 28 September 2014. Uploaded on 12 June 2010. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.