When you step into a dark room, your hand automatically reaches for the light switch. But what if there wasn’t a light to switch on? Our ancestors had to rely on oil or gas lamps, candles, and firelight to navigate their homes at night.

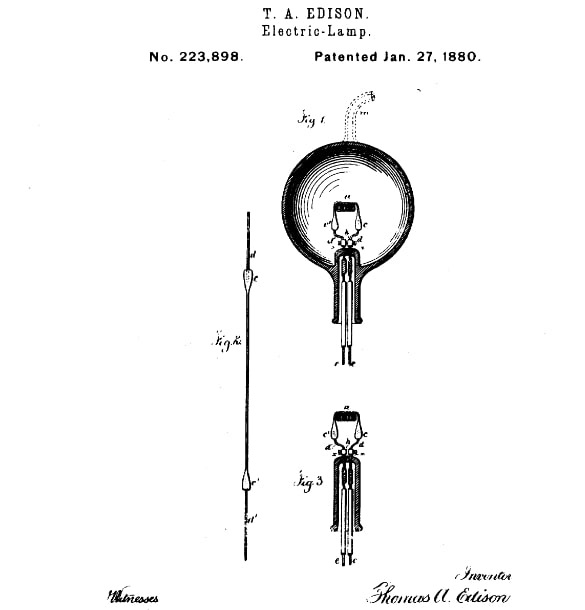

Then on 27 January 1880, the brilliant inventor Thomas Edison received U.S. Patent #223898 for his “Electric-Lamp,” and the world was forever changed.

Edison didn’t invent electric lighting in the 19th century – arc lamps already existed for street lights, but they hissed and flickered. Dozens of inventors worked on the concept of an incandescent electric light bulb, including Sir Joseph Swan in England, but early light bulbs burned out too quickly.

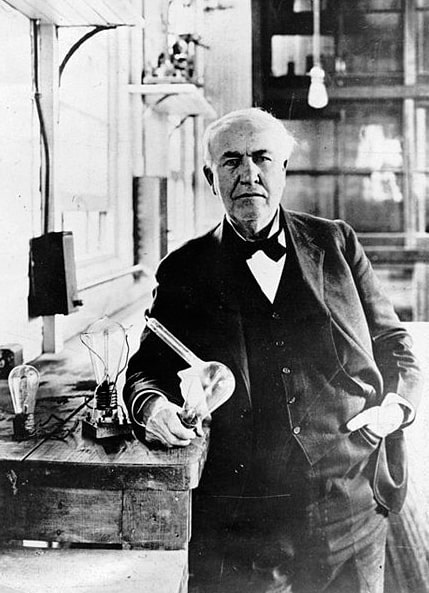

As was often the case with his particular genius, Edison took existing ideas and perfected them. The main problem was the filament inside the light bulb – the material that had to glow with a bright intensity without burning out. Originally, he experimented with platinum, but that metal was rare, expensive, and wasn’t quite doing the trick. Then genius – and perhaps luck – combined. As the following newspaper article explained:

“Were it not for Edison’s genius, his next step might seem almost accidental. Sitting one night in his laboratory, reflecting on his nearly perfected platinum lamp, he began to roll between his fingers a piece of compressed lampblack mixed with tar for use in his telephone. Happening to glance at the threadlike substance, he suddenly realized it might make an even better filament. When subsequent experiments proved that he was on the right track, he discarded platinum and went again to carbon for a brighter, more lasting filament. After countless experiments with cotton thread, wood, straw and other materials, he finally discovered that paper or cardboard, baked in iron molds so that only the wispy carbon structure remained, gave the most satisfactory results. With the perfecting of the carbon filament, he quickly brought incandescent lighting from infancy to commercial possibility.”

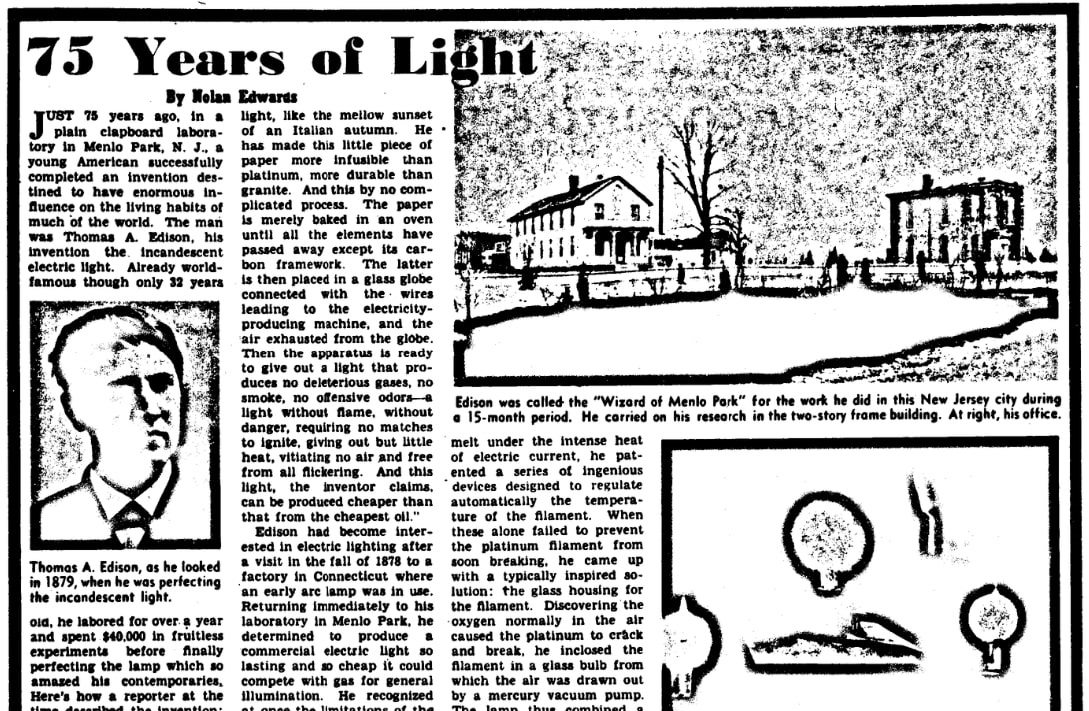

This newspaper article reprinted a reporter’s remarks from 1879, when Edison first successfully demonstrated his new invention. The wonder of this breakthrough is reflected in the reporter’s words:

“Edison’s electric light, incredible as it may appear, is produced from a little piece of paper – a tiny strip of paper that a breath would blow away. Through this little strip of paper is passed an electric current, and the result is a bright, beautiful light, like the mellow sunset of an Italian autumn. He has made this little piece of paper more infusible than platinum, more durable than granite… Then the apparatus is ready to give out a light that produces no deleterious gases, no smoke, no offensive odors – a light without flame, without danger, requiring no matches to ignite, giving out but little heat, vitiating no air and free from all flickering.”

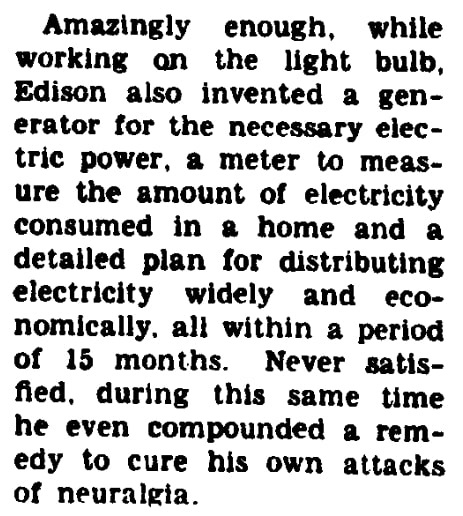

Edison didn’t stop there. As the article concludes:

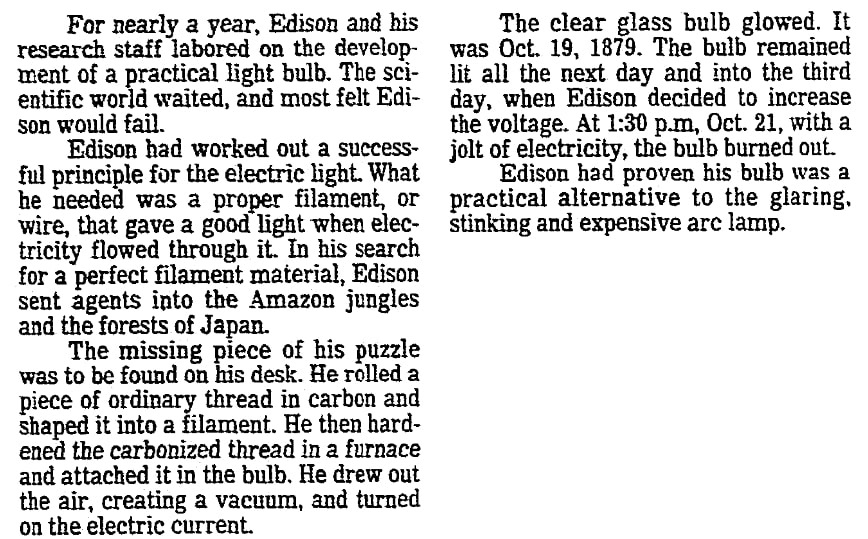

One should never underestimate how hard Edison and his staff worked on this invention, as the following newspaper article explained:

Pleased with the progress he had made, Edison applied for a U.S. patent on 4 November 1879. While waiting for a decision from the Patent Office, he gave public demonstrations of his incandescent electric light bulb at his Menlo Park research lab in New Jersey.

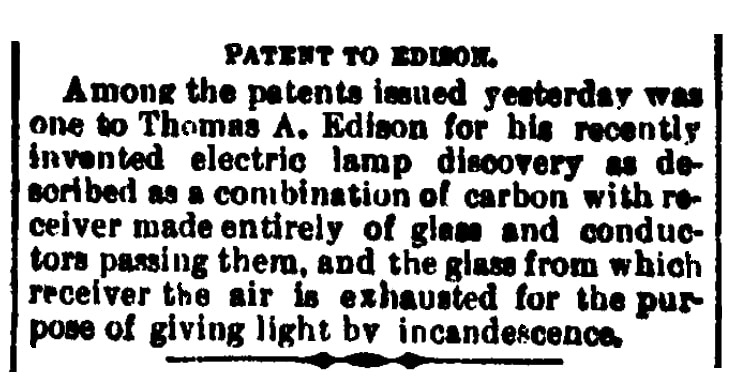

On 27 January 1880, Edison received his patent, as reported in this newspaper article.

Here is the first page of U.S. Patent #223898 for Thomas Edison’s “Electric-Lamp.”

So, the next time you step into a dark room and reach for the light switch, smile and think of Thomas Edison, whose invention illuminated the whole world.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Related Articles: