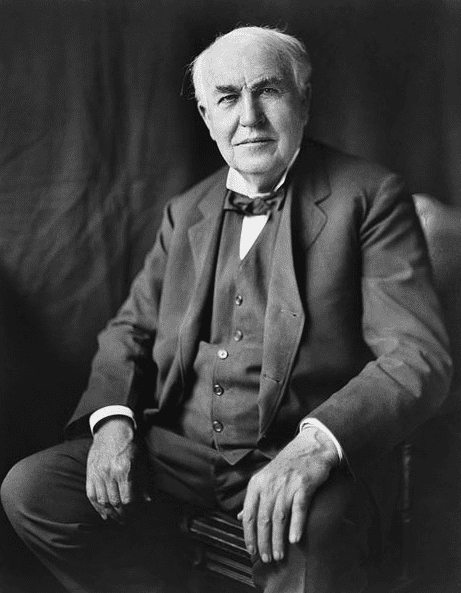

You cannot help wondering: when someone came up with a truly incredible invention, did people at the time immediately grasp what a marvel it was? On 21 November 1877, Thomas A. Edison invented the phonograph, and his contemporaries instantly understood that he had created a form of immortality. Imagine, they wondered, at being able to hear the voice of a long-dead politician, a famous person from history – or even your own grandmother.

Edison’s initial emphasis was not on musical recordings, but rather preserving the sound of the human voice: a form of dictation machine. Shortly after he invented the phonograph it was described in the journal Scientific American; newspapers picked it up from there, and soon the general public was reading about this astonishing machine that could make someone’s voice immortal.

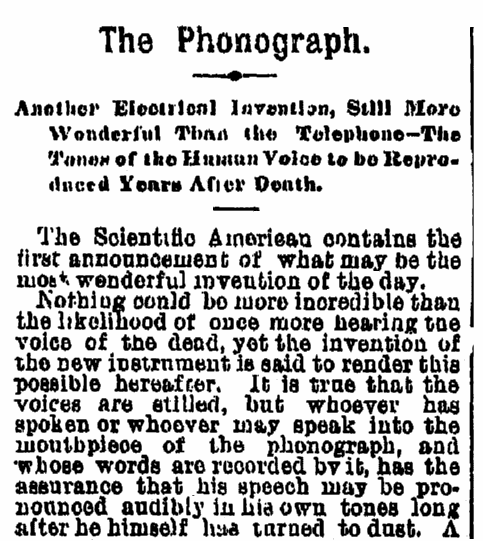

In the following newspaper article, note that the reporter is quick to grasp the significance of Edison’s phonograph. He speculates on a future with talking books, for example, and being able to listen to classical music in the comfort of your own apartment.

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Phonograph.

Another Electrical Invention, Still More Wonderful than the Telephone – The Tones of the Human Voice to Be Reproduced Years after Death.

The Scientific American contains the first announcement of what may be the most wonderful invention of the day.

Nothing could be more incredible than the likelihood of once more hearing the voice of the dead, yet the invention of the new instrument is said to render this possible hereafter. It is true that the voices are stilled, but whoever has spoken or whoever may speak into the mouthpiece of the phonograph, and whose words are recorded by it, has the assurance that his speech may be pronounced audibly in his own tones long after he himself has turned to dust. A strip of indented paper travels through a little machine, the sounds of the latter are magnified, and posterity centuries hence hear us as plainly as if we were present. Speech has become, as it were, immortal. The Scientific American says:

The possibilities of the future are not much more wonderful than those of the present. The orator in Boston speaks, the indented strip of paper is the tangible result; but this travels under a second machine which they may connect with the telephone. Not only is the speaker heard now in San Francisco, for example, but by passing the strip again under the reproducer he may be heard tomorrow, or next year, or next century. His speech in the first instance is recorded and transmitted simultaneously, and indefinite repetition is possible.

The new invention is purely mechanical – no electricity is involved. It is a simple affair of vibrating plates thrown into vibration by the human voice. It is crude yet, but the principle has been found, and modifications and improvements are only a matter of time. So also are its possibilities other than those already noted. Will letter writing be a proceeding of the past? Why not, if by simply talking into a mouthpiece our speech is recorded on paper and our correspondent can by the same paper hear us speak? Are we to have a new kind of books? There is no reason why the orations of our modern Ciceros should not be recorded and detachably bound, so that we can run the indented slips through the machine and in the quiet of our own apartments listen again and as often as we will to the eloquent words. Nor are we restricted to spoken words. Music may be crystallized as well. Imagine an opera or an oratorio sung by the greatest living vocalists thus recorded and capable of being repeated as we desire.

A description of the phonograph is contained in the following letter:

To the Editor of the Scientific American:

In your journal of November 3, page 278, you made the announcement that Dr. Rosapedy and Prof. Marey have succeeded in graphically recording the movements of the lips, of the veil of the palate, and the larynx, and you prophecy that this, among other important results, may add possibly to the application of electricity for the purpose of transferring these records to distant points by wire.

Was this prophecy an intuition? Not only has it been fulfilled to the letter, but still more marvelous results achieved by Mr. Thos. A. Edison, the renowned electrician of New Jersey, who has kindly permitted me to make public not only the fact, but the modus operandi. Mr. Edison, in the course of a series of extended experiments in the production of his speaking telephone, lately perfected, conceived the highly bold and original idea of recording the human voice upon a strip of paper, from which at any subsequent time it might be automatically redelivered with all the vocal characteristics of the original speaker accurately reproduced. A speech delivered into the mouthpiece of this apparatus may fifty years hence – long after the original speaker is dead – be reproduced audibly to an audience with sufficient fidelity to make the voice easily recognizable by those who were familiar with the original. And yet the apparatus is crude, but is characterized by that wonderful simplicity which seems to be a trait of all great inventions and discoveries. The principles are: There is first a speaking tube provided with a mouthpiece, at the base of which is a metallic diaphragm which responds powerfully to the vibrations of the voice. In the centre of the diaphragm is secured a small chisel-shaped point. Below this point is a drum revolved by clock, and serves to carry forward a continuous fillet of paper, having throughout its length and exactly in the centre a V-shaped boss, such as would be made by passing a fillet of paper through a Morse register with the lever constantly depressed. The chisel point attached to the diaphragm rests upon the sharp edge of the raised boss. If now the paper be drawn rapidly along, all the movements of the diaphragm will be recorded by the indentation of the chisel-point into the delicate boss – it, having no support underneath, is very easily indented. To do this, little or no power is required to operate the chisel. The tones of small amplitude will be recorded by slight indentations, and those of full amplitude by deep ones. This fillet of paper thus receives a record of the vocal vibrations of the air-waves from the movement of the diaphragm, and, if it can be made to contribute the same motion to a second diaphragm, we shall not only see that we have a record of the words, but shall have them respoken; and if that second diaphragm be that of the transmitter of a speaking telephone, we shall have the still more marvelous performance of having them respoken and transmitted by wire at the same time to a distant point.

The reproductor is very similar to the indenting apparatus, except that a more delicate diaphragm is used. The reproductor has attached to its diaphragm a thread, which in turn is attached to a hair-spring, upon the end of which is a V-shaped point resting upon the indentations of the boss. The passage to the indented boss underneath this point causes it to rise and fall with precision, thus contributing to the diaphragm the motion of the original one, and thereby rendering the words again audible. Of course Mr. Edison, at this stage of the invention, finds some difficulty in producing the finer articulations, but he is quite justified, by results obtained from his first crude efforts, in his prediction that he will have the apparatus in practical operation within a year. He has already applied the principle of his speaking telephone, thereby causing an electro-magnet to operate the indenting diaphragm, and will undoubtedly be able to transmit a speech made upon the floor of the Senate, from Washington to New York, record the same in New York, automatically, and by means of speaking telephones redeliver it to the editorial ear of every newspaper in New York. In view of the practical inventions already contributed by Mr. Edison, is there anyone prepared to gainsay his prediction? I, for one, am satisfied it will be fulfilled, and that, too, at an early date.

–Edward H. Johnson, Electrician

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors invent something? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Articles: