Introduction: In this article – the first in a series of three articles celebrating Thanksgiving – Jane Hampton Cook shows the impact of the Pilgrims and their first Thanksgiving in America’s early history. Jane is a presidential historian and author of ten books, including her new book Resilience on Parade: Short Stories of Suffragists & Women’s Battle for the Vote. She is the author of Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War. She was the first female White House webmaster (2001-03). Her works can be found at Janecook.com.

Today more than 35 million people can trace their genealogy to the Mayflower Pilgrims. I barely missed it. My ancestor William Hampton traveled on the Bona Nova in the same caravan with the Mayflower for a little while in 1620, until his ship broke away and headed for Virginia instead. The Mayflower now famously disembarked at Plymouth Rock in Massachusetts 400 years ago in December 1620.

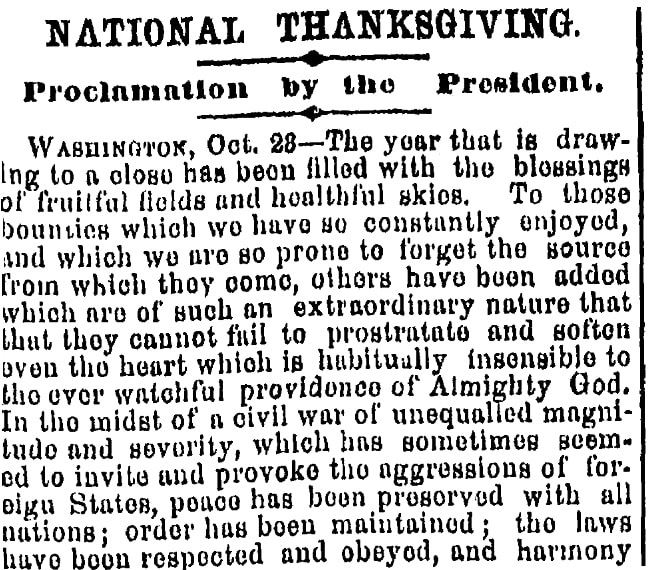

Over 100 years after that, in the 1730s and 1740s, newspapers came of age as a commodity through the efforts of newspaper publishers such as Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Adams. Though it didn’t become a national holiday until President Abraham Lincoln encouraged all Americans to observe a day of Thanksgiving in 1863, GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives show us the impact of the Pilgrims and their first Thanksgiving in America’s early history.

The Pilgrims founded Plymouth Colony, governed themselves under the Mayflower Compact, and developed a relationship with the Wampanoag native tribe. Only 52 of the original 102 Mayflower passengers survived their first winter. Grateful for their blessings despite their losses, a year later they invited the Wampanoag and held the now-famous feast known as Thanksgiving.

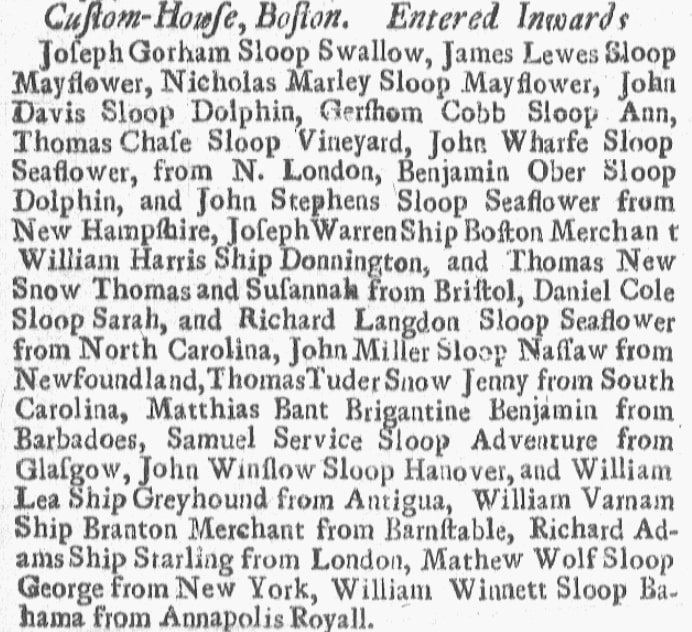

The name Mayflower continued to be a popular ship name well into the 1700s. For example, two sloops called Mayflower arrived in Boston on 30 May 1720, as reported in the Boston Gazette.

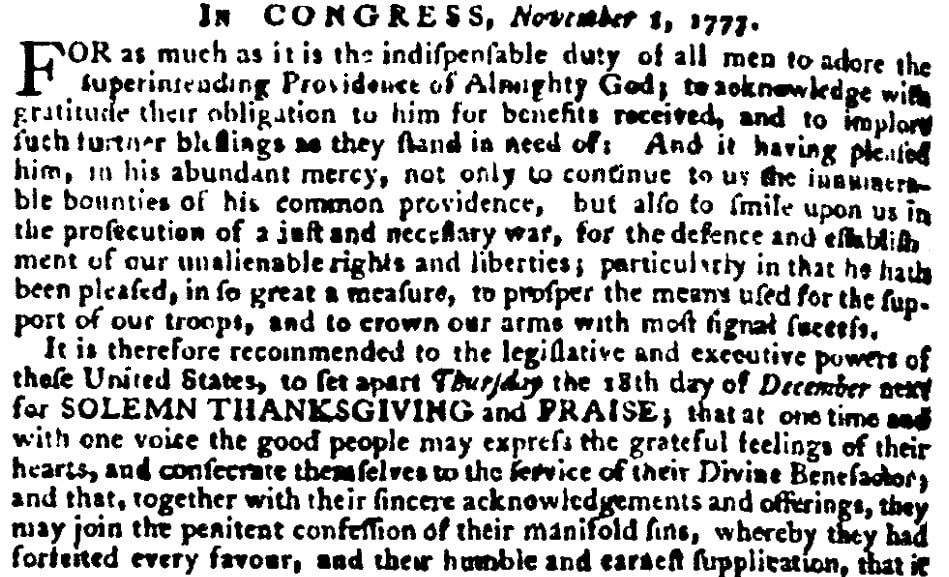

The practice of giving thanks for special occasions and events remained part of America’s culture in the two centuries that followed the Pilgrims’ arrival in the New World. Governors would frequently set aside a day of thanks for special occasions. During the American Revolution in New York, the Battle of Saratoga in 1777 was a much-needed victory that convinced the king of France to support the patriots. This turning point led the Continental Congress to issue a call for Americans around the nation to give thanks.

Newspapers published the proclamation, including the Virginia Gazette on 14 November 1777. Acknowledging the “superintending Providence of Almighty God,” Congress was grateful that Providence had smiled upon them during this “just and necessary war” for the “defense and establishment of our unalienable rights and liberties.” They set aside 18 December 1777 as a day for “solemn Thanksgiving and praise; that at one time and with one voice the good people may express the grateful feelings of their hearts.”

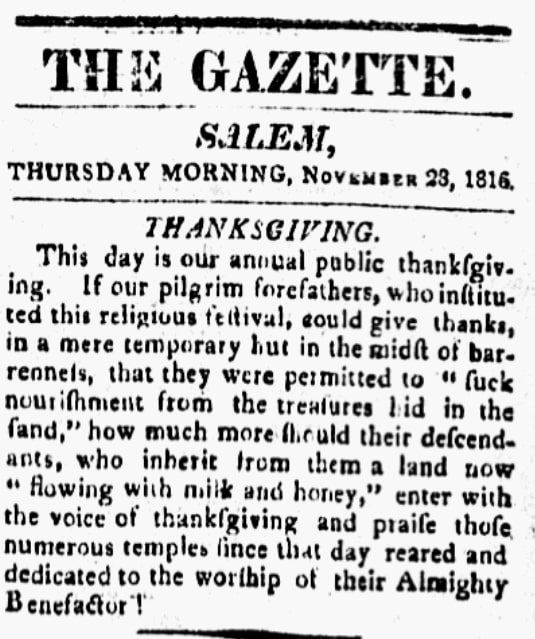

Thanksgiving proclamations remained common throughout the beginning of the new Republic. Likewise, the people of New England continued to celebrate an annual Thanksgiving feast. The story of the Plymouth Pilgrims was not forgotten, as the Salem Gazette showed in 1816.

While New Englanders continued to have an annual feast, Thanksgiving as an annual holiday wasn’t uniformly practiced throughout the United States until after the Civil War. But as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives show, the ingredients of occasional days of Thanksgiving and the annual Thanksgiving feasts of New Englanders created a recipe ripe for the national holiday we now celebrate.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Related Article: