Introduction: In this article, Gena Philibert-Ortega shows how helpful government publications can be for your family history research. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

How do you search GenealogyBank? Most likely you enter a name or a keyword into the search engine, then take a look at your historical newspaper search results. But could you be missing other information?

Once you conduct your search, you will receive a list of results. The default collection for this results list is GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives. It’s definitely the strongest collection GenealogyBank offers: more than 15,000 newspapers, with 95% of them not found on any other website.

But as important as newspapers are to your family research, there are other kinds of records that are helpful to genealogists. For that reason, GenealogyBank offers other collections in addition to its newspapers.

Collections on GenealogyBank include: Obituaries, the U.S. Federal Census, the Social Security Death Index, Government Publications, and Historical Books. Once you conduct a search your results list will include boxes labeled with these collections and the number of results found in each collection. By clicking on the box of interest, you can see the results for your search in that collection. This can help you find additional information that you otherwise wouldn’t see with your initial (newspaper default) search.

Government Publications: An Example

I like to research cemeteries, so I conducted a search on the GenealogyBank homepage using the keyword “cemetery” in the “Include these keywords” box. Although in this example I’m using a non-ancestor search, government publications can also be found naming people, events, or activities. And keyword searches can lead you to information about an ancestor.

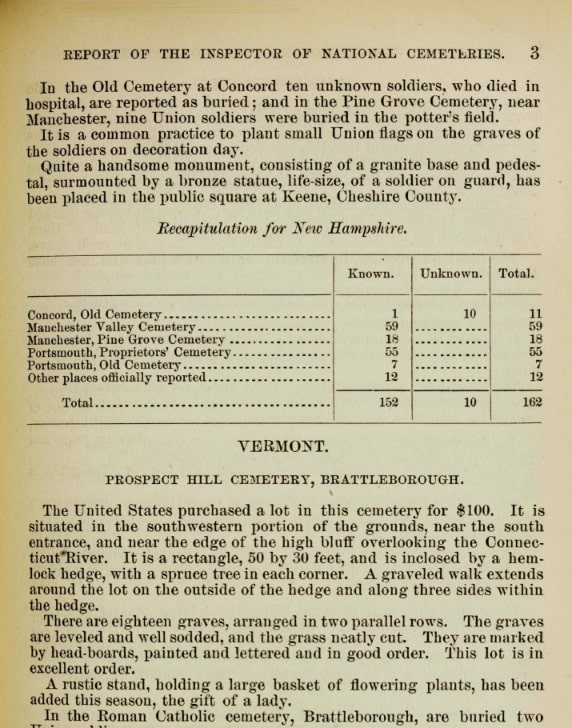

One of the results in my cemetery search was from 26 February 1875 and had the rather dull title of Letter from the Secretary of War Transmitting, in Obedience to Law, the Report of the Inspector of National Cemeteries of the Year 1874. As I explored this government report, I realized that it listed military and nonmilitary cemeteries around the United States, their condition, their description, and statistics about burials.

This work mostly deals with Union burials from the Civil War; however, there is mention of “rebel” or Confederate burials, and citizens. Some reports are comprehensive and others are not. But this information can help me understand everything from how many unnamed burials there are in a cemetery, to the condition of that cemetery in 1874 (which would help me understand the possibility of finding information in 2024), to a history of the cemetery where my ancestor is buried. Although this government publication doesn’t list names of the deceased, it can still be beneficial to my family history research.

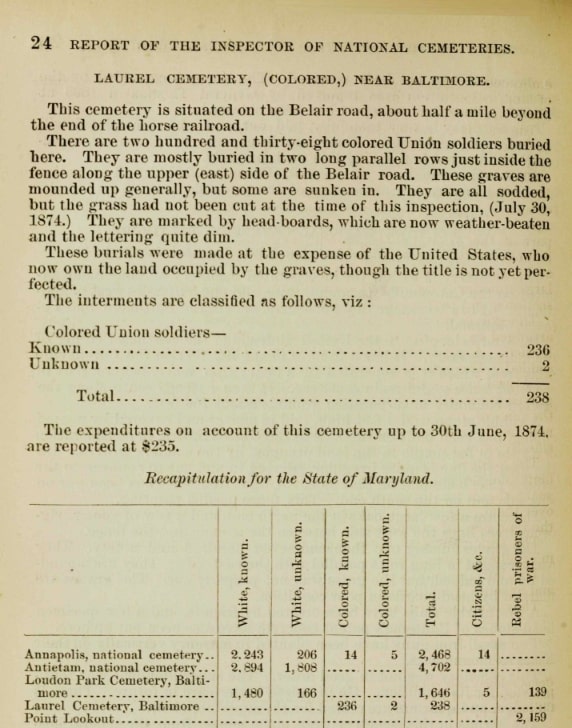

For example, this is the report on Laurel Cemetery, which is listed as a “colored” cemetery near Baltimore, Maryland.

Notice that it states:

“There are two hundred and thirty-eight colored Union soldiers buried here.”

Of these, 236 are known by name and 2 are unknown. The report states that some of the graves are sunken in and that the grass had not been cut when it was inspected on 30 July 1874. The burials were “marked by headboards which are now weather beaten and the lettering quite dim.”

I may want to do more research on that cemetery to fully understand its history and what its condition is today. Conducting a simple Google search I found the website, Laurel Cemetery Memorial Project, which provides a history of the cemetery and a list of burials. Combining this government publication, historical newspapers, and this Memorial Project website, I can better understand the burials and history of this cemetery.

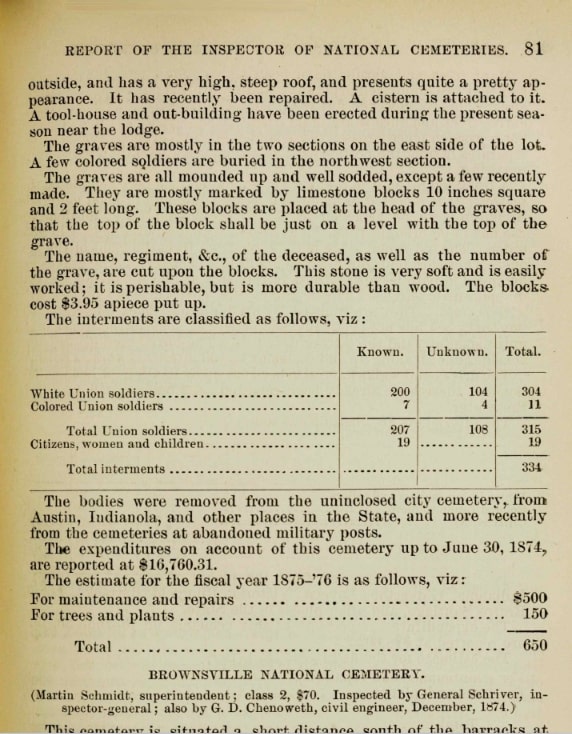

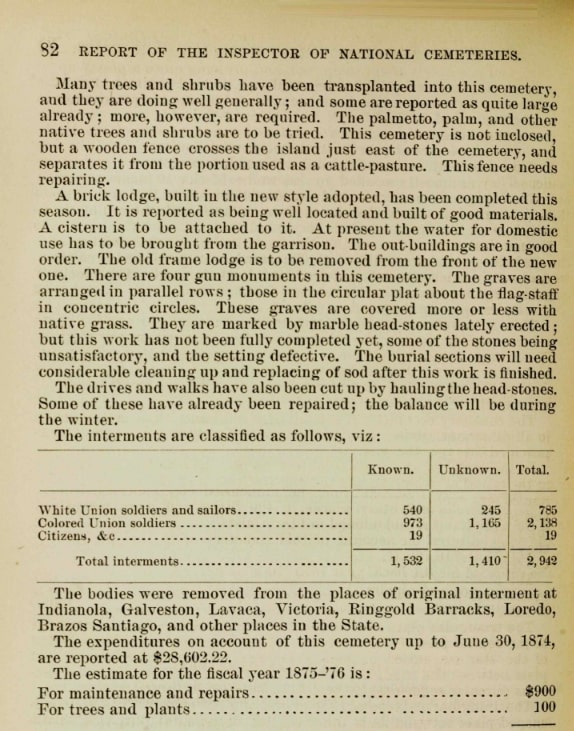

Helpful to the Civil War researcher, especially in cases where a family member’s burial may be unknown, entries in this government report include information about where soldiers were interred prior to reburial. Consider this entry for Brownsville National Cemetery, Texas:

“The bodies were removed from the places of original interment at Indianola, Galveston, Lavaca, Victoria, Ringgold Barracks, Loredo, Brazos Santiago, and other places in the state.”

The New Hampshire section of this report states:

“There is no soldiers’ lot in any cemetery in this State; at least none is officially reported: but Union soldiers are buried with their friends in several cemeteries.”

Pine Grove Cemetery is listed as having Union soldiers buried in a potter’s field. We often think of potter’s fields as where the impoverished are laid to rest. This note helps us understand that that’s not always the case.

Don’t Forget Government Publications

This is just one example of what the Government Publications on the GenealogyBank website can provide. Applications for pensions, requests for land, and other dealings with the government can also be found here. When you conduct a search, don’t forget to look at the results for each collection. GenealogyBank is much more than just a great newspaper collection!

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: Soldiers National Monument at the center of Gettysburg National Cemetery in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Credit: Henryhartley; Wikimedia Commons.