Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry writes about a long-ago scandal: the Foster probate case in 1900 was a court case and a genealogist’s dream – a hearing about a contested will decided in part by a family Bible and evidence dug up from a grave. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

When Oliver Sidney Foster, a wealthy brick manufacturer of Revere, Massachusetts, passed on 24 September 1898, he left an estate of more than $225,000 and no written will. His daughter, Jennie (Foster) Kimball, applied to be Administratrix and was granted such. All seemed flush for Jennie until she ordered Henry J. Foster off one of the properties.

Uncle Henry protested and rounded up his siblings to dispossess Jennie. On 25 April 1899 George, Edward, Henry and Maria (Foster) Bennett appeared in court to contest Jennie as a legal heir of the estate on the grounds that her mother, Ellen “Nellie” J. Brown, was never legally married to their brother Oliver. The hearing was set for October 1900.

The genesis of this claim came about when Henry Foster paid a visit to town clerks George L. Vincent of Sommerville, Massachusetts, and Warren Fenno of Revere, who both confirmed that no legal document could be found validating the marriage of Oliver Foster and Nellie Brown.

The Foster clan were confident they would be victorious – but they were no match against Jennie, who mounted a strong defense involving many witnesses and key pieces of evidence, including an item dug up from her mother’s grave!

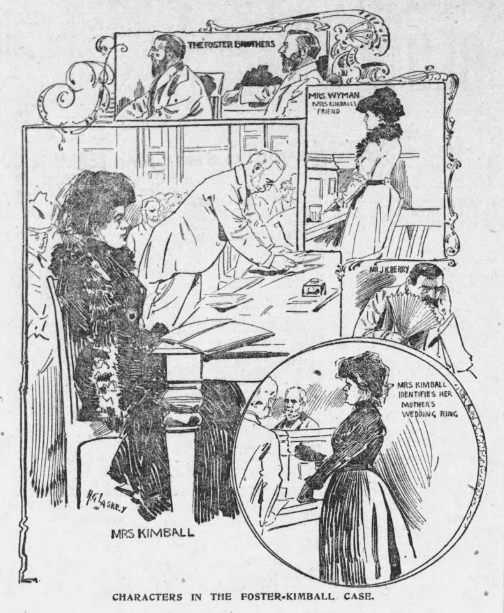

October came and Judge John W. McKim presided over one of the most unusual cases in his career at the Suffolk County Probate Court. The room was packed; the legal matter was an instant “theatrical sensation.”

The case received press coverage nationwide. In a lengthy and detailed newspaper article, the Boston Herald began with these headlines.

Jennie’s attorney, Alfred Hemenway, presented evidence which included over 60 witnesses, a family Bible, fabric from Nellie Foster’s wedding dress, and a silver inscription plate from a coffin bearing the name FOSTER.

Earlier, Jennie had ordered the excavation of her mother’s grave to gain access to the silver name plate for evidence. Newspapers reported on this macabre aspect of the case.

The photograph of Nellie Foster’s little tombstone inscribed “My Wife” in Kittery, Maine, was presented along with testimony from Edward J. Murphy, who made the grave marker.

The family Bible used in evidence recorded the marriage between Oliver Sidney Foster and Ellen J. Brown on 14 February 1860, and the birth of Jennie Mabel Foster on 26 April 1862. The signature of Oliver was in pencil and Nellie’s was written in ink.

Some of the witnesses who testified included:

Edward H. Lovell, a cashier at the Winnisimett National Bank where Oliver served as a board director, confirmed that the pencil signature in the Bible matched the handwritten signature of Oliver Foster.

Bartlett W. Weeks, who worked on Oliver’s Connecticut estate, submitted documents signed by Oliver which matched the Bible signature. Francis W. Kittredge, Oliver’s lawyer, provided deeds signed by Oliver which also matched the signature in the Bible.

Kittredge testified that he met with Oliver at his home in Revere on 1 April 1898. Jennie was present during this meeting and Oliver declared “I have only one heir,” and pointed to Jennie.

Dr. William Fiske Whitney testified that he treated Nellie before her death at Massachusetts General Hospital and she was registered under the name of Foster. Also, a death certificate from the town of Arlington, Massachusetts, dated 6 March 1875, listed Nellie J. Foster.

Jennie also rallied a few allies from the Foster camp willing to testify on her defense and her legitimacy. Mrs. Martha Allen, sister of Oliver, produced a piece of the brown silk that matched the material to the wedding dress. Mary Bumpus of Woburn, first wife of Oliver’s brother Henry J. Foster, told the court she often paid a call to the Fosters at their home in Somerville and never doubted their legal union. She also confirmed the fabric sample.

Others who made a positive identification on the brown silk fabric were Hannah Searles of Charlestown and Mrs. L. Sawyer, who said she saw Nellie wearing the dress at a dance in Stoneham – and Nellie told her Oliver fancied it and she intended to wear it on her wedding day.

Commissioner John P. Prichard and his wife Elizabet both declared that there was a valid marriage between Oliver and Nellie. Mr. Prichard remembered when Oliver courted Nellie and recalled that a band appeared before their home to celebrate their marriage. Philip Ham also noted the courtship between the couple and recalled how the neighborhood jested about Oliver “waiting on such a handsome woman.” Oliver told him “I am going to marry her,” and “the wedding will be at Mr. Washburn’s home where Nellie worked.”

John K. Berry, a watchman at the State House, testified that his brother attended the wedding of Nellie and Oliver held at David Washburn’s home. He remembered the slice of the wedding cake his brother brought to him.

The court reports revealed bad blood between the Foster siblings and Nellie. Georgianna (Russell) Hobbs of Arlington testified that in 1874 Nellie fled the love nest and moved in with her parents George and Harriett Russell.

Georgianna’s husband, Melnotte Augustus Hobbs, testified that Oliver’s siblings forged a rift between the couple and Nellie had to flee.

Several witnesses, mostly Oliver’s employees, testified that he pined for his Nellie and tried to reconcile with her.

Sylvester Buzzwell, a bricklayer, testified that Oliver told him he was proud to be the husband of “Nel” even though his family thought of her as a two-bit gold digger.

John Baptiste testified that Oliver told him his wife Nellie had a baby and he missed her. Oliver wanted him to go to the Russell home and coax Nellie into returning to him. Baptiste told the court he met with Nellie and she would only agree to a reunion if Oliver came to her and ditched his brothers.

Alvin W. Osborn stated that Oliver pointed to the Russell home and told him, “That is the place my wife went after leaving me; perhaps you can go see her and get her to come home.”

Lydia A. Ebberlin testified that she acted on Oliver’s behalf to bring about a reunion. Nellie agreed, but she fell ill and never recovered. She died a few months later.

Other witnesses that appeared in the proceedings included: George Buxton, Mary Wyman, Mathew Rowe, James A. Beam, and Samuel T. Littlefield.

When Judge McKim made his final ruling making Jennie the legal administrator, she burst into tears of joy! Jennie had not only won a fortune but saved her parents’ good name and that is priceless.

Genealogy Note: Oliver Sidney Foster (1835-1898), son of Abram Foster (1798-1873) and Esther Taylor (1791-1880). Ellen “Nellie” Jane Foster (1842-1875), daughter of Atkinson Brown and Almira Mitchell (1822-1871). Jennie Mabel Foster married William Shaw Kimball (1859-1922), son of Stephen Kimball (1825-1885) and Ellen Lord (1839-1906). The couple lived in Revere, Massachusetts, and had a son, Sidney Frank Kimball (1879-1925).