Introduction: In this article, Katie Rebecca Merkley continues her series exploring our ancestors and appearances of Easter in the newspaper, examining the period 1775-1783. Katie specializes in U.S. research for family history, enjoys writing and researching, and is developing curricula for teaching children genealogy.

This installment of the Easter newspaper series focuses on mentions of Easter in Revolutionary War-era newspapers. I searched GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives for the keyword “Easter” and narrowed the results down to 1775-1783. Just like in the colonial era (see Part 1), not many mentions of Easter were found in newspapers for this time period.

Photo credit: https://depositphotos.com/home.html

I have chosen four of them to highlight in this article. In some of the newspapers found, Easter was used as a name.

1779: A Ship Named Easter

John Pitts was master of a ship called Easter. In 1779 he ran ads in the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury from March 15 to April 5 for passage to Topsham and Exeter, England. Coincidentally, Easter that year was April 4, the eve of his apparent last day running the ad.

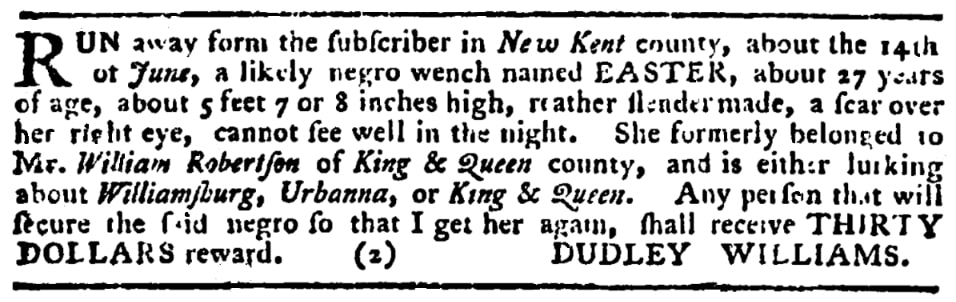

1779: A Runaway Slave Named Easter

Later that year, in Virginia, an enslaved woman named Easter ran away from her enslaver. When indentured servants or enslaved persons ran away, their masters would publish ads describing them and offering a reward for their return. The interest of the masters was to reclaim their human “property.” In the present day, these ads hold interest to the descendants of the runaways because of the information it gives about the ancestor.

Easter had run away in New Kent County around 14 June 1779. She was 27, tall and skinny, had a scar over her right eye, and couldn’t see well at night. It can be speculated that whatever injury left the scar also ruined her vision, and it is easy to wonder whether her master had inflicted that injury.

Easter had formerly belonged to William Robertson of King & Queen County. Dudley Williams posted the ad. When researching enslaved persons, it is essential to know the name(s) of the owner(s). This ad lists two owners. A bill of sale might have been created when William Robertson sold Easter to Dudley Williams,

assuming the change of masters was due to a sale. If the men were related, Dudley Williams may have inherited Easter from William Robertson, in which case she’d be mentioned in Robertson’s probate records.

Also note that the ad was published in November 1779, approximately five months after the purported escape. The person who posted the ad suspected Easter was “lurking about Williamsburg, Urbanna, or King & Queen.” Was Easter hiding that long? Or did she run farther than her master suspected?

While the runaway ad reveals much information that can help a descendant of Easter find her, it also leaves many questions that need to be answered by other records. Knowing the names of an owner and former owner will tremendously help anyone researching her or ancestors in her situation.

1781: Mary-Easter Gets Married

In 1781, another person with Easter in her name was mentioned. On “Saturday last,” Miss Mary-Easter Isaacs married Mr. Evan Malbone. The announcement was published on 18 October 1781 in the Connecticut Journal. Looking up a 1781 calendar reveals that October 18 that year was a Thursday, so the Saturday before was 13 October 1781.

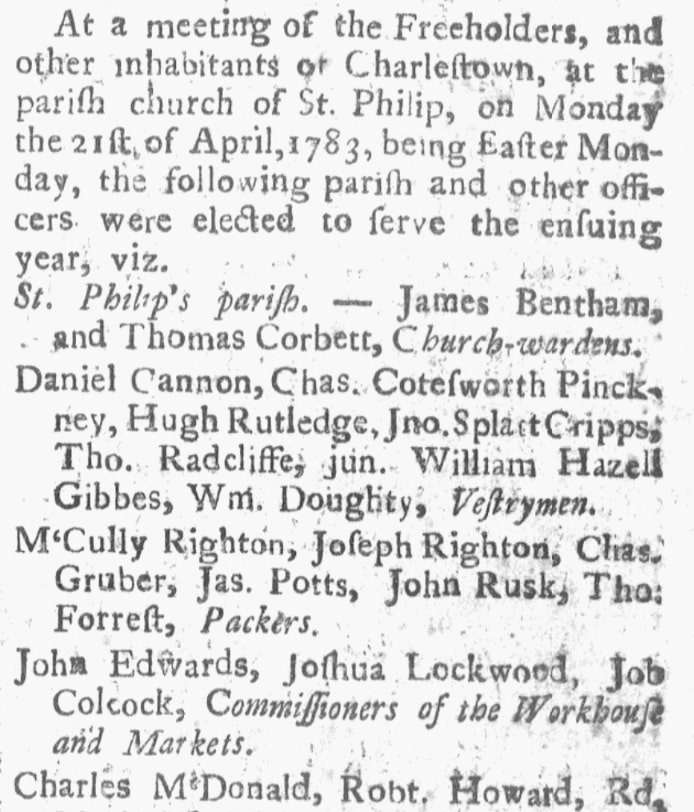

1783: Political Meetings on Easter Monday

In 1783, political meetings occurred on Easter Monday in Charleston, South Carolina. An article listing people newly appointed to offices was posted five days after the meeting.

What does an ancestor’s name being on such a list mean? The list proves that each person on it was a resident of that town and very likely highly involved in their community. It is possible that many of the people on this list knew each other. Some may have been related to each other by blood or marriage.

If you find your ancestor on a list like this, you have evidence of his involvement in his community and possible FAN (Family, Associates, Neighbors) club members.

These four examples show that Easter was mentioned in Revolutionary War-era newspapers, but – just like in the colonial period – none of these newspaper articles mentioned Easter celebrations. We learned that Easter was a name used in various ways during this time. A political meeting on Easter Monday indicates that offices were not closed that day. There is no indication from this sampling of newspapers that our ancestors from that era celebrated Easter (other than going to church, which wouldn’t be a newsworthy event). If Easter was celebrated, it wasn’t discussed in newspapers.

The next installment of this series will focus on Easter in newspapers during the Civil War.

Happy Easter and springtime!

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: Happy Easter. Credit: https://depositphotos.com/home.html

Related Article: