Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry continues her story about two brothers, William and Francis Jackson, who helped fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad in Massachusetts. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

I continue with my story on the Underground Railroad – a flourishing system of routes, safe houses and sympathizers in the 19th century that helped slaves escape the South and head north to free states and Canada.

You can find a goldmine of stories on the Underground Railroad in a collection of old newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives. A Boston Herald article published in 1971 featured New England families who helped run the Underground Railroad and pave a way to freedom for escaped slaves.

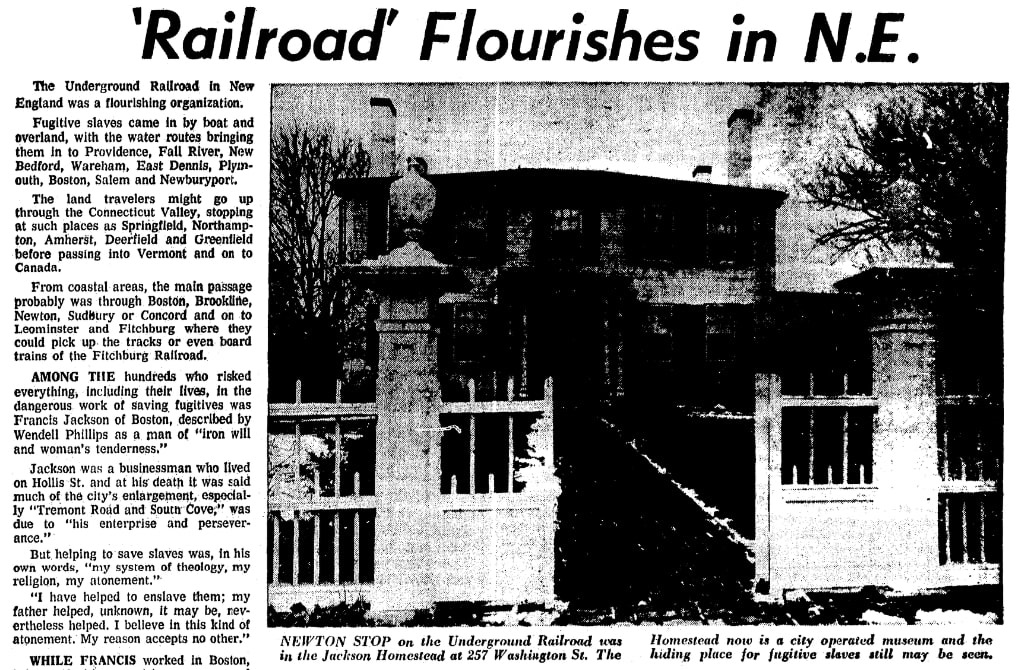

Massachusetts brothers Francis and William Jackson opened their homes on Hollis Street, Boston, and 527 Washington Street, Newton, to fugitive slaves, and raised funds for their journey to freedom. Francis’ records and letters are online at Digital Commonwealth and other online archives.

William Jackson had a large family, and many of his children inherited his ardent anti-slavery views and became very active in the struggle to end human bondage.

One daughter, Ellen Dorinda Jackson, kept a record of events at the house, and his granddaughter, Louise Jackson Keith, preserved oral lore. Ellen published Annals from the Old Homestead, and additional written accounts are preserved at the Newton History Museum, formerly her family home.

According to the Boston Herald article:

“The slaves would be kept in a cellar room [in the William Jackson home] while, often, a group of Newton women would be gathered upstairs sewing clothes for the current and future fugitives. If there was an alarm the fugitive would be dropped in a fieldstone-built well, about the size of a barrel. Boards would be placed over the opening and vegetables piled on top as thought that section of the basement was a cooling closet.

“On one occasion, it has been said, a mother and her child were hidden in the well during a search. The baby began to cry when the opening was boarded over. Fortunately, five of the youngest Jackson children were in a nursery right above the hiding place.

“They began to cry when the baby did. The squalling of five children successfully masked the cries of the fugitive baby, who later was sent on to Canada with her mother.”

The risks undertaken were considerable, since providing this kind of aid was dangerous work: fugitive slave laws made it illegal to provide support to escaped slaves. The Boston Herald article also provided these details:

“She [William Jackson’s daughter Ellen, in her diary] said her father would be awakened by pebbles tossed against his window, and would hide the fugitive or fugitives through the night or as long as was necessary before transporting them 15 miles to the next [Underground Railroad] station, possibly in Sudbury.

“Jackson undoubtedly received fugitives from his brother [Francis] in Boston and, possibly, from such other abolitionists as Ellis Gray Loring and Lewis Tappan [who married William’s daughter Sarah Jackson], both of whom lived in Brookline.”

Alice Fanny Jackson, in Three Hundred Years American; The Epic of a Family from Seventeenth-Century New England to Twentieth-Century Midwest, describes a visit to the William Jackson home (which was in the family for 10 successive generations) when she dined with Louise Jackson Keith, who was the current occupant.

“Mrs. Louise (Jackson) Keith invited us to dinner, showed us family portraits, the genealogical tree drawn by Francis Jackson, and other heirlooms. In the cellar we saw the old dry well, once Edward’s ‘pure water well’ and long afterward a station of the underground railway for fugitive slaves.”

Stay tuned for more!

Related Articles: