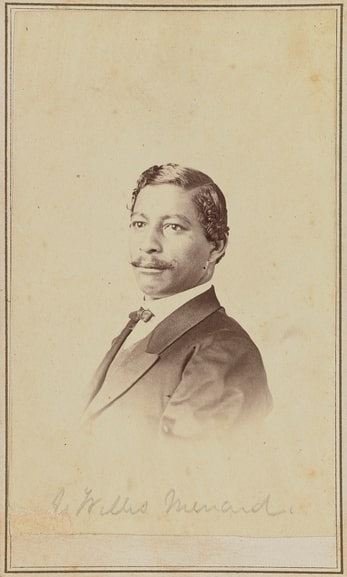

John Willis Menard is not a familiar name, even to most historians, but on 3 November 1868, he nearly achieved something that would have secured his name in the nation’s history: first African American elected to Congress.

This near-historic event occurred in the confusing world of Reconstruction politics in post-Civil War Louisiana. James Mann, the white Democratic congressman representing Louisiana’s Second Congressional District, died before his term expired. Accordingly, during the presidential election of 1868, Louisiana citizens also voted for a replacement for Mann.

It was a ragged election, fraught with irregularities, and the votes of 12 entire parishes were thrown out. When the dust settled, Menard won the seat with 5,107 votes. However, a white Democrat, Caleb S. Hunt, contested Mann’s election even though Hunt only received 2,838 votes.

The House of Representatives investigated the matter and decided not to seat either man. Future president James A. Garfield, one of the congressmen on the House committee examining the contested election, is alleged to have remarked that “it was too early” for an African American to be admitted to Congress. Therefore, although he appeared to have achieved a historic first and become the first African American elected to Congress, the 30-year-old Menard was denied that privilege.

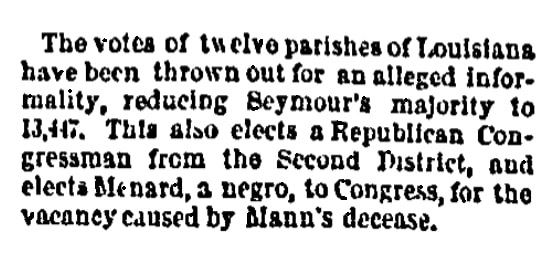

The following four newspaper articles describe Menard’s contested 1868 election. This first article shows that the election in Louisiana was news elsewhere in the country. This article was printed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Here is a transcription of this article:

The votes of twelve parishes of Louisiana have been thrown out for an alleged informality, reducing Seymour’s majority to 13,447. This also elects a Republican Congressman from the Second District, and elects Menard, a negro, to Congress, for the vacancy caused by Mann’s decease.

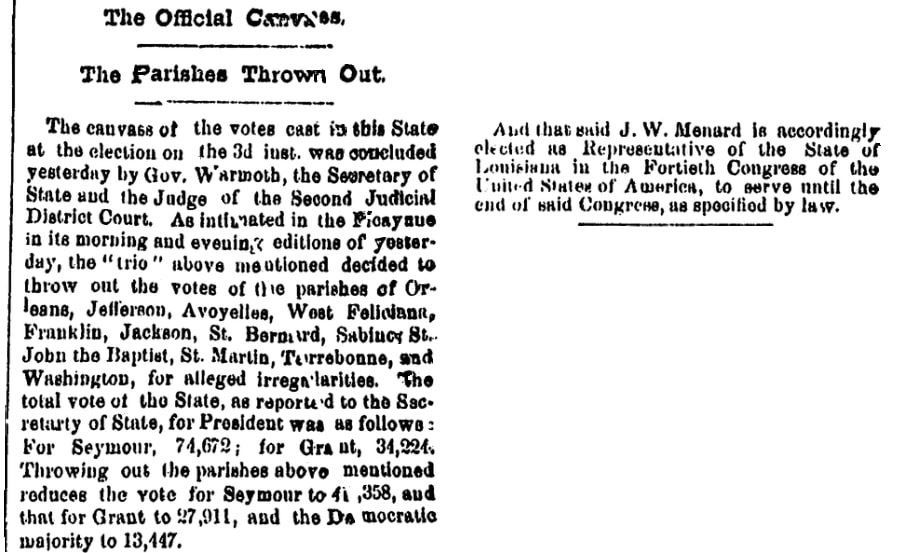

The contested election of course was big news in the Louisiana papers. This article was printed by the Daily Picayune.

Here is a transcription of this article:

STATE ELECTION RETURNS.

The Official Canvass.

The Parishes Thrown Out.

The canvass of the votes cast in this State at the election on the 3d inst. was concluded yesterday by Gov. Warmoth, the Secretary of State and the Judge of the Second Judicial District Court. As intimated in the Picayune in its morning and evening editions of yesterday, the “trio” above mentioned decided to throw out the votes of the parishes of Orleans, Jefferson, Avoyelles, West Feliciana, Franklin, Jackson, St. Bernard, Sabine, St. John the Baptist, St. Martin, Terrebonne, and Washington, for alleged irregularities. The total vote of the State, as reported to the Secretary of State, for President was as follows: for Seymour, 74,672; for Grant, 34,224. Throwing out the parishes above mentioned reduces the vote for Seymour to 41,358, and that for Grant to 27,911, and the Democratic majority to 13,447.

…And that said, J. W. Menard is accordingly elected as Representative of the State of Louisiana in the Fortieth Congress of the United States of America, to serve until the end of said Congress, as specified by law.

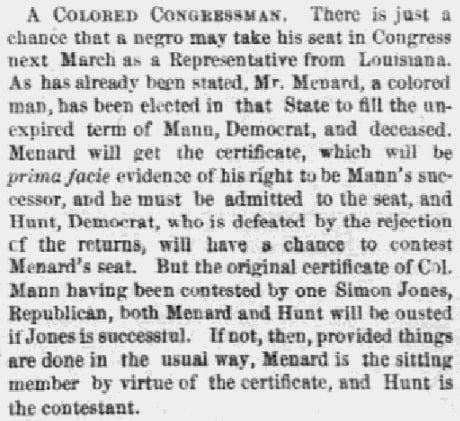

Here is a transcription of this article:

A COLORED CONGRESSMAN.

There is just a chance that a negro may take his seat in Congress next March as a Representative from Louisiana. As has already been stated, Mr. Menard, a colored man, has been elected in that State to fill the unexpired term of Mann, Democrat, and deceased. Menard will get the certificate, which will be prima facie evidence of his right to be Mann’s successor, and he must be admitted to the seat, and Hunt, Democrat, who is defeated by the rejection of the returns, will have a chance to contest Menard’s seat. But the original certificate of Col. Mann having been contested by one Simon Jones, Republican, both Menard and Hunt will be ousted if Jones is successful. If not, then, provided things are done in the usual way, Menard is the sitting member by virtue of the certificate, and Hunt is the contestant.

When it became apparent Menard’s election would be contested and there was a chance he would not be seated, the Times-Picayune published a lengthy editorial in protest. This diatribe covers a range of issues all involved in the Menard case: the election of an African American to Congress, the proper procedure Congress should follow in disputed elections, fair treatment for Louisiana under the Reconstruction Acts, and the pervasive issue of states’ rights.

Here is a transcription of this article:

THE LOUISIANA CONGRESSIONAL ELECTIONS.

The Washington dispatches say of the late congressional elections in Louisiana that –

It seems to be the general impression that Congress will not allow any contested cases to grow out of that election, but reject all the members and compel a new election after the 4th of March next, under the proper protection.

The constitutional provision under which the present and former Congresses have justified all their proceedings in the rejection of so many Democrats who were elected, and the exclusion of so many State representatives, is that which declares “each House” to be “the judge of the elections, returns and qualifications of its own members.”

Neither House is to be “judge” of the election returns or qualifications of the other; nor can both Houses together, which make a Congress, judge for either House. The House of Representatives decides for itself, as the Senate decides for itself. It is equally plain, that a House of Representatives, deciding for itself, cannot decide for its successor. A new House of Representatives is a new political body, in which the right to judge for itself is as complete as was that of its predecessor to judge for itself.

It follows that the House of Representatives at Washington cannot take any step in regard to the members of Congress elected to the next House. Legally their decisions would not be worth a straw. The members duly chosen, with the credentials thereof from the proper State authority, would be entitled to claim their seats at the opening of the next Congress, notwithstanding any declaration, resolution or law, passed by this Congress, vacating their seats.

Such action would indeed open a new source of controversy; but the next House would only assert its own dignity by disregarding the claims of any persons presenting themselves under a subsequent election, and by assuming its own privilege to judge of the election returns and qualifications of its own members. It might under malign influences refuse seats to the members now chosen; but it would be by virtue of its own powers, and not because a preceding House has invaded its prerogative in advance. The only legitimate jurisdiction the present House has in the matter is to decide on the lawfulness of the election in the Second District, for Mr. Mann’s vacancy. It is assumed, in the dispatch we have quoted, that Congress – meaning the House – will not allow any contest; but will throw out all the members elected, including Mr. Menard, to whom Gov. Warmoth has given a certificate, notwithstanding he was defeated by ten thousand majority. But Mr. Menard is a partisan of their own sect – the first man of African descent sent to claim a seat, and, therefore, entitled to a more gracious reception than to be thrown over without “contest” – that is, without the inquiry into facts and proofs which is included in the idea of “contest.” A contest implies two parties, and when, therefore, it is said that Congress (the House) will not allow a contest, it means that the case should not be heard between claimants. But if there be no claimants allowed how can the House take jurisdiction or determine the validity of an election? It is only by a contest for filling of this vacancy that the facts come up at all. There must be parties to the controversy. There cannot be made a John Doe and Richard Roe case of fictitious parties, through whom a judgment can be enforced by a single House of Congress to annul the entire vote of a state cast according to law.

Congress, in its legislative capacity, may take up the question and attempt to affect the same end by law, passing both Houses, with the assent of the President or over his veto. But that would be the exercise of a very different power from that of each House over its own members. It would be based on a naked claim of Federal authority to set aside State elections, by its own supreme will, on the suggestion of local causes, of the sufficiency of which Congress is to be the judge. Louisiana, under the operation of the Reconstruction Acts, confirmed by a formal recognition of this Congress, is as much a State in the Union as New York or Massachusetts. The power of revising local elections for local causes, is as perfect in regard to them as in regard to us. The same supreme will which can annul the results of a State election – by one decree affecting a whole state, on the suggestion of a political party, could set aside the elections in any other State for a similar cause, or any other cause which defeated partisanism can set up for results that disappoint them. The power claimed puts the results of the election in all the States in the power of those who may happen to have the control of Congress. It asserts a magnitude of Federal usurpations over the internal affairs of States, which is, indeed, not greater in degree than that which has been exercised already in the destruction of the Southern State Governments; but is of an application so universal, and assails numerous and powerful States in their pride, and in their most vital interests, so directly, that we apprehend it will meet with a degree of opposition which no outrage upon the South could ever raise into vigor of action.

We, therefore, look for more caution in the dealing with this topic than the newspaper scribes are disposed to attribute to the Radicals in Congress. We do not think they will meddle by law, this session, with the Louisiana elections, and that Mr. Menard will be got rid of by a device. His case will not be permitted to be contested, because the House has the privilege of declaring that there is no vacancy to be filled. Mr. Jones will be pronounced to have been entitled to Mr. Mann’s seat all the time, and be put into the vacancy, as a sort of stop-gap, until the new House takes up the question of elections and eligibility of its own members, when, perhaps, the Louisiana cases will be taken up in a manner becoming the gravity of the questions they raise.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Articles: