In one of the most controversial decisions in the nation’s judicial history, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its Dred Scott v. Sandford decision on 6 March 1857, ruling that Blacks could not be citizens in the United States and were not protected by the U.S. Constitution. The Court also ruled that Congress could not prohibit slavery in federal territories. For good measure, the Court stated that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was unconstitutional.

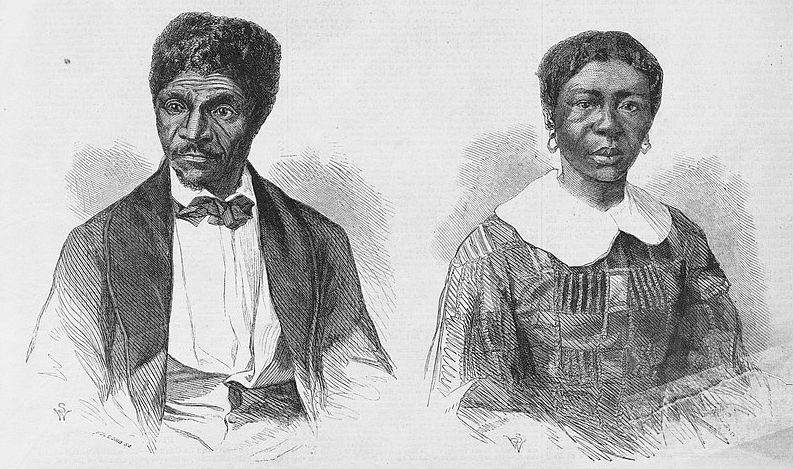

Dred Scott was a slave who sued for freedom on behalf of himself and his family, basing his argument on the fact that his master had brought Scott to live for several years in the state of Illinois (a free state) and the territory of Wisconsin (a free territory). Since he lived in areas where slavery was illegal, Scott argued, he could not be considered a slave. When his current master refused to allow Scott to buy freedom for himself and his family, Scott sought justice in the nation’s court system.

His long legal ordeal began with a lawsuit in a Missouri court in 1846 and eventually went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court handed down its infamous decision by a 7-2 majority in 1857, with Chief Justice Taney declaring in the official opinion of the Court that the Founding Fathers, in writing the U.S. Constitution, considered all persons of African descent “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

When the U.S. Supreme Court issued its infamous Dred Scott Decision, the Court hoped to put the slavery controversy to rest. How wrong it was! The slavery issue only became more divisive, and instead of threatening to tear the nation apart it actually did just that four years later, when the Civil War began.

The separation between anti- and pro-slavery factions can be seen in the following two editorials – one from a Northern newspaper ridiculing the Dred Scott Decision, and the other expressing a Southern perspective supporting the Supreme Court’s ruling. Following the two editorials, there are two more articles reporting on the Dred Scott Decision.

Here is a transcription of this article:

THE DRED SCOTT CASE.

The decision in this case is calculated to stir up as great an excitement at the north against the accursed institution of slavery as any event that has preceded it. The able and common sense view of Judges McLean and Curtis, which were given on Saturday, reveal to the people that even the Supreme Court is composed of fallible men, who cannot agree one with another. If two may be wrong, so may five, and thus arguing, citizens will begin to feel a contempt for the decisions of all courts, and hold with Jefferson that the opinions of our Judges are worth no more than those of so many private citizens, and should be treated with no more respect. We give the substance of Justices McLean and Curtis’ opinion, showing a wide difference between them and a majority of the Court.

Judge McLean says Slavery is limited to the range of the state where it is established by municipal law. If Congress deems slaves or free colored persons injurious to a territory they have the power to prohibit them from becoming settlers. The power to acquire territory carries the power to govern it. The master does not carry with him to the territory the law of the state from which he removes. Hence the Missouri Compromise was constitutional and the presumption is in favor of freedom. Dred Scott and his family were free under the decisions of the last 28 years.

Judge Curtis dissented from the opinion of the majority of the Court as delivered by Chief Justice Taney, and gave his reasons for the dissent. Judge Curtis maintained that native-born colored persons can be citizens of the state and of the United States. That Dred Scott and his family were free when they returned to Missouri. That the power of Congress to make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory was not as the majority of the Court expressed, limited to territory belonging to the United States at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, but has been applied to five subsequent acquisitions of land. That Congress has power to exclude slavery from the territories, having established eight territorial governments without, and recognized slavery in six, from the time of Washington to J. Q. Adams.

The majority decision is received by evident alarm by all the northern press. It is a declaration of eternal war between slavery and freedom, we are afraid; of eternal war between the Free and Slave States. “Sectionalism” must rule hereafter, for even the Supreme Court is divided North and South.

This second editorial was published by the Baltimore American (Maryland was a slave state) and reprinted by the Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, Virginia – Virginia was also a slave state).

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Baltimore American, speaking of the decision of the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case, says: “We are not so quixotic as to suppose that this or any decision will quiet the sectional excitement of the country upon the slavery question. The right to agitate is one that no judicial authority can limit, and so long, as in this case, agitation is the lever that works upon prejudices for the attainment of political power, it will be resorted to. But the decision will have power in backing the exertions of conservative men; it will force anti-slavery agitation into a more open and avowed field of opposition to Southern institutions not out of, but in Southern States, and will give to the friends of Southern rights a vantage ground they cannot fail to occupy. Briefly expressed, it will put the latter upon solid, safe and conservative ground of Constitutional law as authoritatively defined, whilst it will drive their opponents from behind the shelter of disputed points, and force them to take their position upon the open field of hostility to the Constitution as it now exists. Wilmot provisos and Congressional restrictions upon the rights of inhabitants of territories are henceforth banished from the armory of sectional agitation. They are no longer allowable weapons.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Opinions of the U.S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott Case.

Washington, March 6.

Chief Justice Taney delivered today the opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case. The points are that Scott is not a citizen; that he was not manumitted [i.e., emancipated] by being taken by his master when a slave into the then Territory of Illinois; and that the Missouri Compromise was an act unconstitutionally passed by Congress.

Justice Nelson, of New York, dissented. Five Judges, Taney, Campbell, Catron, Wayne and Daniel, concur on the constitutional point against the Missouri Compromise. Nelson and Grier dodge by adopting the Missouri decisions for their justification in joining the majority. McLean and Curtis meet the issue squarely and sustain the jurisdiction of the Court, with the constitutionality of the Compromise.

It is no novelty to find the Supreme Court following the lead of the Slavery Extension party, to which most of its members belong. Five of the Judges are slaveholders, and two of the other four owe their appointments to their facile ingenuity in making State laws bend to Federal demands in behalf of “the Southern institution.”

Here is a transcription of this article:

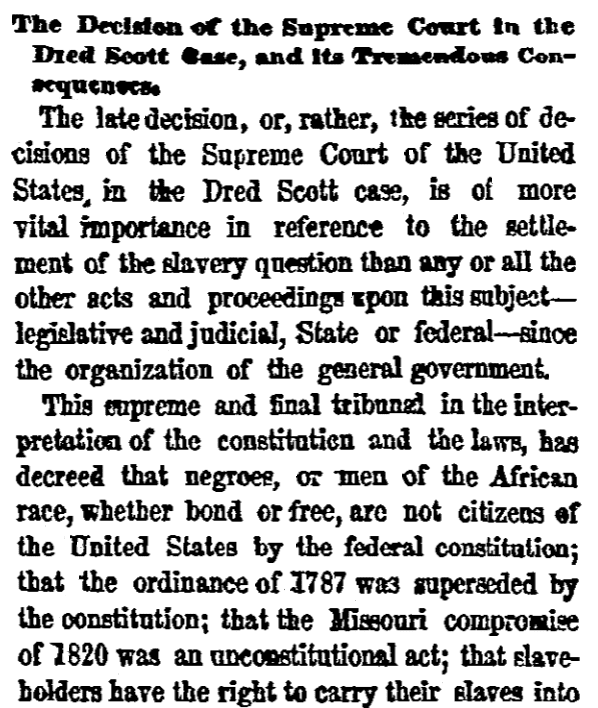

The Decision of the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott Case, and Its Tremendous Consequences.

The late decision, or, rather, the series of decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Dred Scott case, is of more vital importance in reference to the settlement of the slavery question than any or all the other acts and proceedings upon this subject – legislative and judicial, State or federal – since the organization of the general government.

This supreme and final tribunal in the interpretation of the Constitution and the laws, has decreed that negroes, or men of the African race, whether bond or free, are not citizens of the United States by the federal Constitution; that the ordinance of 1787 was superseded by the Constitution; that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was an unconstitutional act; that slaveholders have the right to carry their slaves into the Territories; that the legal condition of a slave in a slave State is not affected by his temporary sojourn in a free State; and that Congress has no power over the question of slavery in a Territory, and cannot delegate any power over the subject to the Territorial Legislatures.

The importance and comprehensive bearings of these decisions cannot be overestimated – they cover all the disturbing party and sectional issues upon the slavery controversy, and strike at the root of the mischief in every case.

First, the supreme judicial tribunal of the Union decides that, according to the Constitution, negroes are not citizens, whether free men or slaves. In other words, ours is the white man’s constitution, and the negro, as a citizen, is absolutely ignored. The consequence is, that all the existing constitutions and laws of the free States elevating negroes to the rights and privileges of citizenship, are null and void; for, in this authoritatively-declared meaning of the Constitution, to be a citizen of a State is to be a citizen of the United States, inasmuch as the Constitution expressly ordains (Art. 4, sec. 2) that “the citizens of each State shall be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States.” This decision, therefore, settles the old difficulty between Massachusetts and South Carolina concerning the free colored citizen cooks and seamen of the former, treated only as dangerous free negroes upon entering the ports of the latter State. The decision is against Massachusetts and her free colored citizens, and in favor of South Carolina.

The decisions concerning the federal ordinance of 1787 and the Missouri Compromise of 1820 establish the full validity of the Kansas-Nebraska bill, as the true constitutional policy in regard to slavery in the Territories. The decision concerning slaves in transitu through a free State, or the temporary sojourn of a Southern slave in a free State, settles the Lemmon case, and all cases like that of Mr. Wheeler of North Carolina, whose slaves, at Philadelphia, were so unceremoniously spirited away; and in all such cases the supreme decree is decisive of the slaveholder’s constitutional rights to his slave property.

But the most important of these supreme decisions, in a political party view, is the judgment that Congress has no power, and can delegate no power over the question of slavery in the Territories. This decision at a single blow shivers the anti-slavery platform of the late great Northern Republican Party into atoms. The policy of legislating slavery out of Kansas and the other Territories of the Union by Congress will no longer avail them. Congress has no power in the premises. That is settled. What was in doubt is in doubt no longer. The supreme law is expounded by the supreme authority, and disobedience is rebellion, treason and revolution. The Republican Party henceforth must choose between submission and revolution – loyalty or treason to the government. The gall and bitterness of the New York Tribune are betrayed in its mad assertion that these vital and final decisions of our Supreme Judges are “entitled to just so much moral weight as would be the judgment of a majority of those congregated in any Washington barroom.” But this madness of our Seward organs will avail nothing. The only alternative to the anti-slavery factions of the North, from the Garrison to the Seward and original Van Buren factions, is loyalty or treason, submission or rebellion.

Unquestionably this bombshell from the Supreme Court, together with the inaugural and the Cabinet of the new administration [i.e., President James Buchanan, inaugurated two days before the Dred Scott Decision], will at once reopen the slavery agitation in all its length and breadth; but henceforth slavery in the Territories is an issue which must be decided by the laws of climate, products, races, and the natural laws of our population and emigration; for Congress henceforth can have nothing to do with the subject. Meantime, the new administration, relieved of the precedents of the Missouri Compromise, the Wilmot Proviso, and all other unconstitutional laws and proceedings of the government during the last forty years on the slavery question, has its course plainly and authoritatively marked out. In this respect Mr. Buchanan is particularly fortunate, and his administration will, we dare say, be singularly satisfactory and successful, for the people are ever loyal to the Constitution and the laws.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Articles: