Introduction: In this article, with Halloween approaching, Melissa Davenport Berry turns her thoughts to witches and writes about the Salem witch trials of 1692. Melissa is a genealogist who has a website, americana-archives.com, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

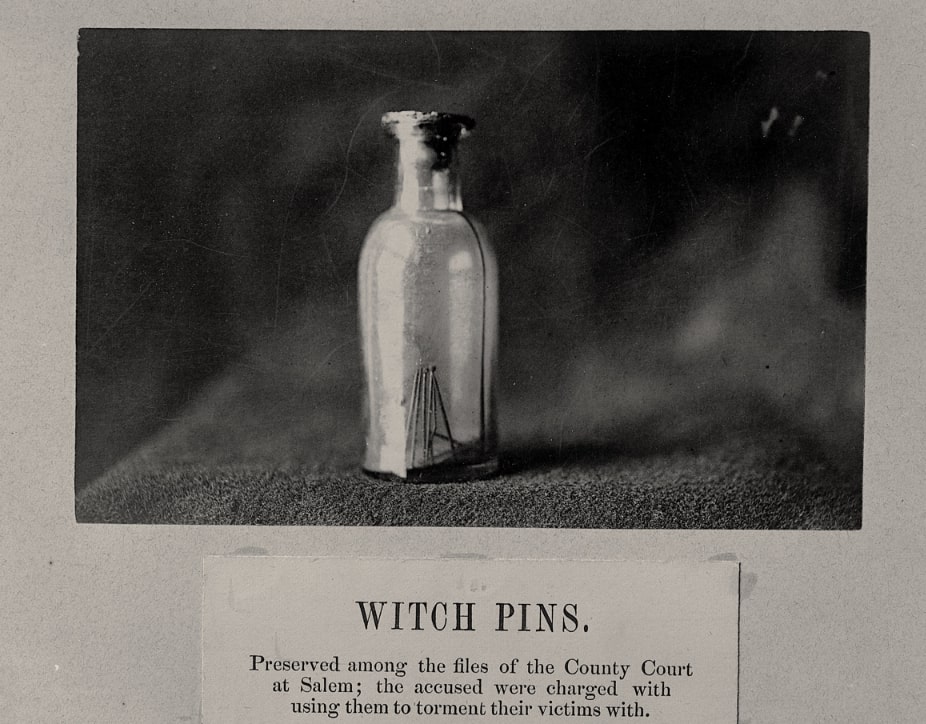

In 1973 Jane Sarnowski, a clerk in the office of the Superior Court in Salem, Massachusetts, made headlines across the country. Many articles featured a photo of Jane with the original court transcripts from the infamous Salem witchcraft trials, sporting a glass bottle of “witch pins” – purportedly the same pins used as evidence in the 1692 trials.

What was the big buzz leaving readers on pins and needles? This photo caption reads:

Jane S. Sarnowski, a clerk in the office of Superior Court at Salem, Mass., displays some witchcraft documents and pins reportedly used in 1692 when teenage girls said they had been put under spells. The Essex County commissioners are in the process of signing a contract for publication of the “Salem Witchcraft Papers: Verbatim Transcriptions of the Court Records: In three volumes,” a translation of the longhand script that contains testimony of the accused witches and their relatives.

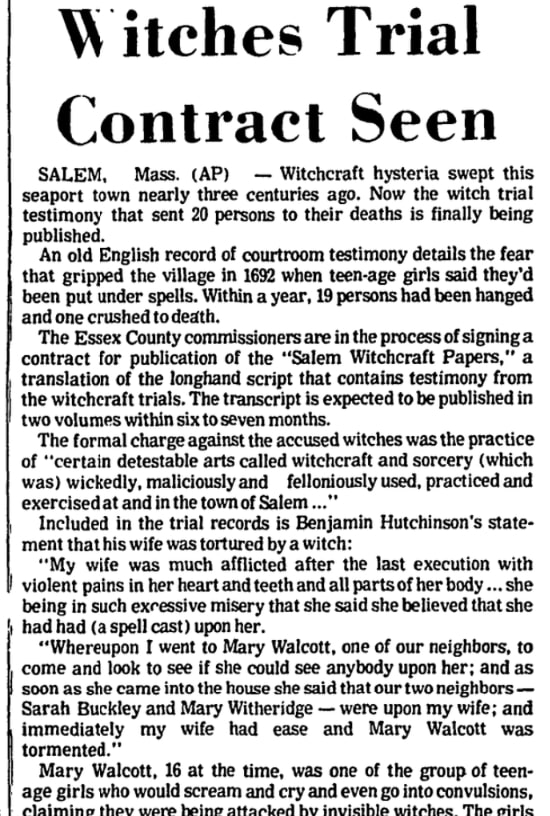

Here is the newsclip accompanying Jane’s photo, spilling the skinny on those “witch pins” that sent many to the gallows.

This article reports:

Witchcraft hysteria swept this seaport town nearly three centuries ago. Now the witch trial testimony that sent 20 persons to their deaths is finally being published…

The formal charge against the accused witches was the practice of “certain detestable arts called witchcraft and sorcery (which was) wickedly, maliciously, and feloniously used, practiced and exercised at and in the town of Salem…”

Included in the trial records is Benjamin Hutchinson’s statement that his wife was tortured by a witch:

“My wife was much afflicted after the last execution with violent pains in her heart and teeth and all parts of her body… she being in such excessive misery that she said she believed that she had had (a spell cast) upon her.

“Whereupon I went to Mary Walcott, one of our neighbors, to come and look to see if she could see anybody upon her; and as soon as she came into the house she said that our two neighbors – Sarah Buckley and Mary Witheridge – were upon my wife; and immediately my wife had ease and Mary Walcott was tormented.”

Mary Walcott, 16 at the time, was one of the group of teenage girls who would scream and cry and even go into convulsions, claiming they were being attacked by invisible witches. The girls later named the witches as friends and neighbors ranging in age from a 5-year-old child to a grandmother.

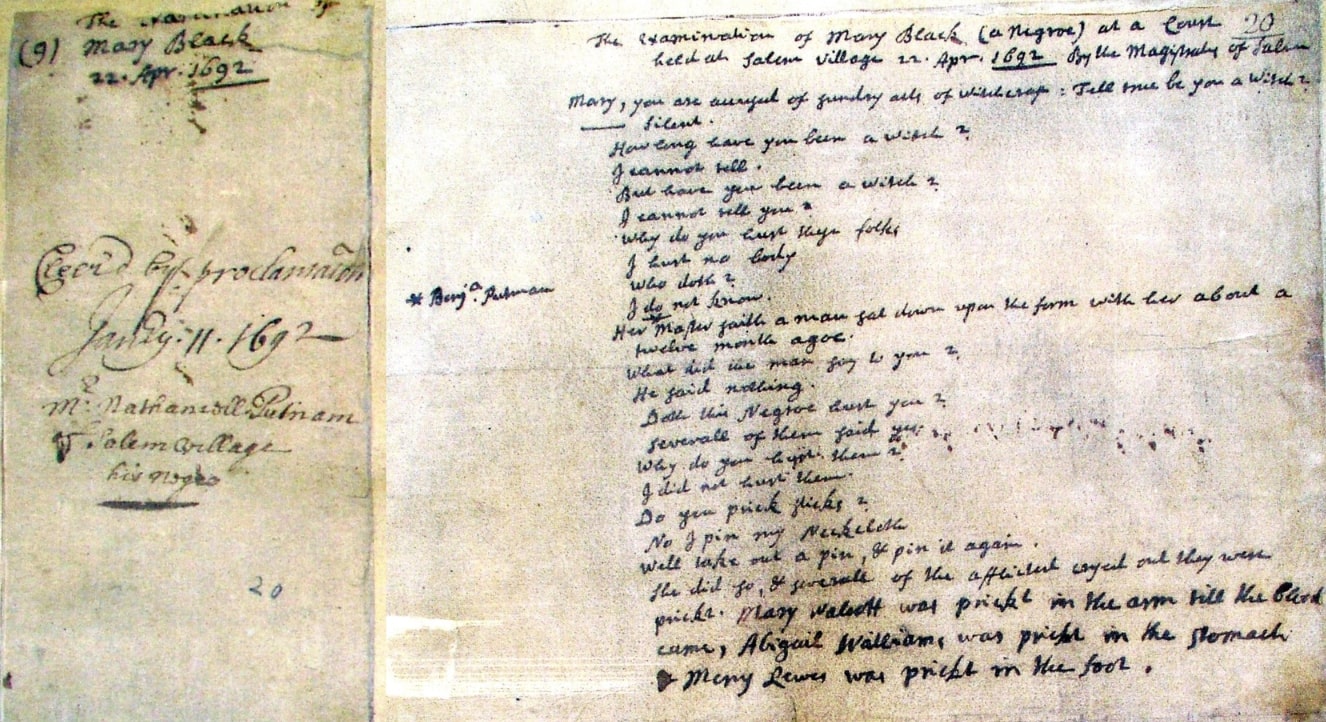

And from the interrogation of Mary Black, an accused witch, on April 22, 1692, by the Salem magistrate:

Q: “Tell me, be you a witch?”

A: Silence.

Q: “How long have you been a witch?”

A: “I cannot tell.”

Q: “But have you been a witch?”

A: “I cannot tell you.”

Q: “Why do you hurt these folks?”

A: “I hurt nobody.”

Q: “Do you prick these girls?”

A: “No, I pin my neckcloth.”

Q: “Well, take out a pin and pin it again.”The transcript continues: “She did so, and all of the afflicted cried and they were pricked. Mary Walcott was pricked in the arm till the blood came, Abigail Williams was pricked in the stomach, and Mercy Lewis was pricked in the foot.”

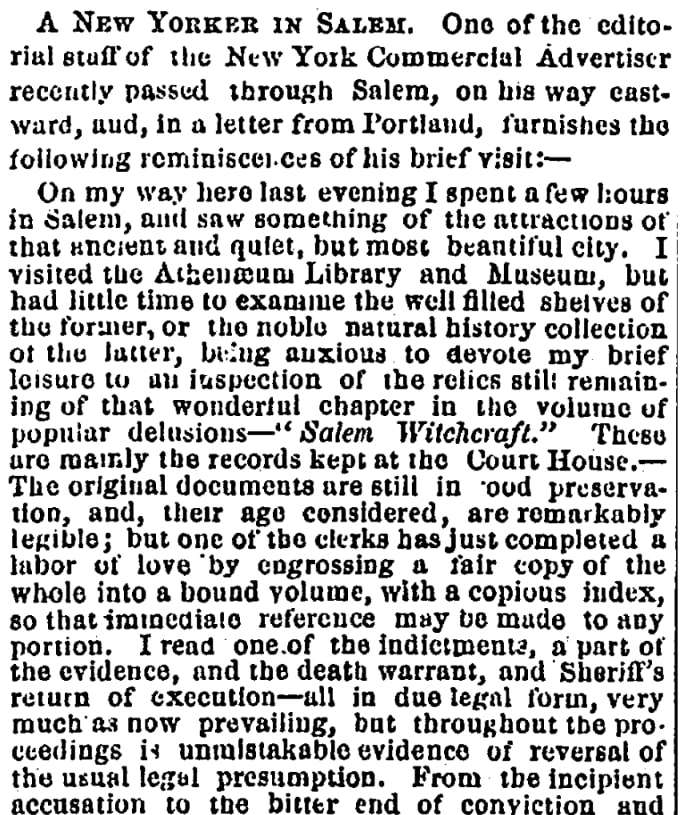

In 1860 the Salem Register published a piece from one of the editorial staff of the New York Commercial Advertiser newspaper who had visited the Salem Athenaeum Library and Museum to view the Salem witch trial documents, and discovered the “witch pins.”

The correspondent writes:

“In connection with the documentary evidence, a few ordinary pins are shown. They were produced [at] the trial, in proof of the torments inflicted on the bewitched through the alleged diabolical practices of these whom they accused, very much as an axe or a pistol is produced in capital cases of the present day, as the instrument with which a murder was perpetrated, These pins were formerly shown in papers, but numbers of them disappeared with a mysterious celerity in keeping with their magical derivation, and the authorities were compelled to resort to the measures adopted in still older times by Solomon, in his dealings with the oriental powers of darkness and the taming of refractory genii, and the remaining pins are now confined, and securely sealed, in a cylinder of glass.”

A photo of the pins that were used as “evidence” in Rebecca Nurse’s trial appears in a Life magazine article “Revisiting the Sites of the Salem Witch Trials.”

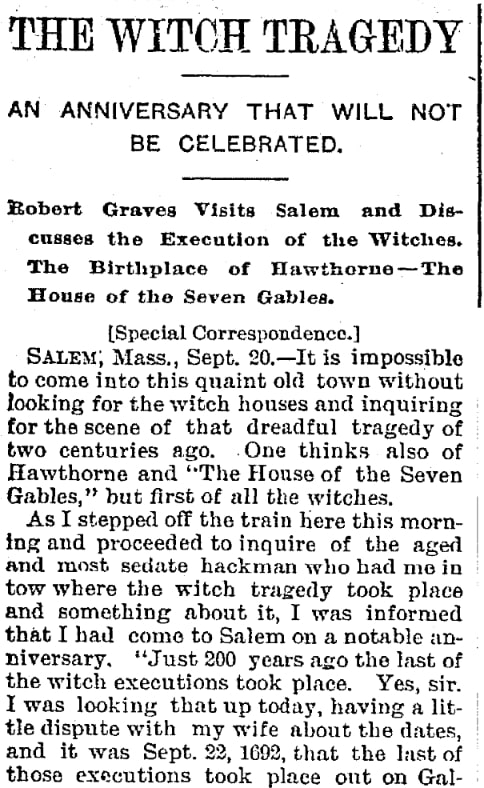

In the fall of 1892 Robert Graves visited Salem and observed the “witch pins” at the courthouse.

Graves writes:

“Here are displayed two authentic souvenirs of one of the most terrible tragedies ever known in America.

“One is a small bottle, protected by the county seal, containing a few rusty pins which were produced in court two centuries ago and identified as the very pins with which the wicked witches pricked and tortured their juvenile victims. These, the most famous pins in history, are curious looking contrivances – twice as long as our modern pins, heads formed of twisted wire, and not so sharp that they need have inflicted much pain upon the deluded victims. These gruesome relics helped to place the rope about the necks of nineteen innocent men and women. They were originally pinned into the papers containing the famous – rather the infamous – trials, but as they disappeared one by one the remainder were placed in the bottle and carefully sealed.”

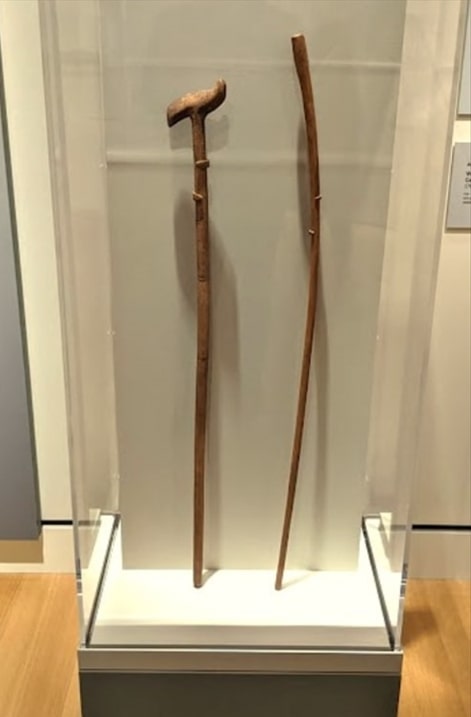

Beside the “witch pins” afflicting the teen queens, some claimed George Jacobs, or the “man with two staves,” afflicted them with his walking sticks and testified he beat and tortured them as a “specter.”

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: witchcraft trial at Salem Village. The central figure in this 1876 illustration of the courtroom is usually identified as Mary Walcott. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Related Articles:

- Witchcraft: Salem Witch Trials

- Witchcraft: Salem Witch Trials, Part 2

- Salem Witchcraft (part 1)

- Salem Witchcraft (part 2)

- Relics of the Salem Witch Trials Era (part 1)

- Relics of the Salem Witch Trials Era (part 2)

- Relics of the Salem Witch Trials Era (Part 3)

- Relics of the Salem Witch Trials Era (part 4)

- Relics of the Salem Witch Trials Era (part 5)

Great story!