Introduction: In this article, James Pylant concludes his story about the “whodunnit” case of Charlie Dorris and a puzzling double slaying. James is an editor at GenealogyMagazine.com and author for JacobusBooks.com, is an award-winning historical true-crime writer, and authorized celebrity biographer.

As I wrote in the opening paragraph of Part 1 of this story: On a quiet summer morning in 1924, gunfire erupting in an exclusive Long Beach, California, apartment left two people dead and a lone survivor to tell what happened. At the center of this story was Charles “Charlie” W. Dorris, whom newspapers dubbed the “Man of Tragedy.”

The photo caption for the above pictures reads:

(Upper left): C. W. Dorris, who is held for questioning. (Upper center): Mrs. Henry S. Meyer, whose husband was slain. (Upper right): Mrs. C. W. Dorris, who was also shot to death. (Lower left): Henry Meyer, the second victim. Below is Meyer’s signature on a [promissory] note that police believe may have caused the fatal argument.

When police arrived at the Eleanor Apartments in Long Beach, California, on 30 June 1924, they found the bodies of Therese Dorris, 57, in the living room and Henry Meyer, 45, in a dressing room. Charlie Dorris, the dead woman’s husband – the lone survivor and witness – said that Meyer had shot her as she approached him. Meyer then accidentally shot himself with two pistols as he and Charlie wrestled over control of the weapons.

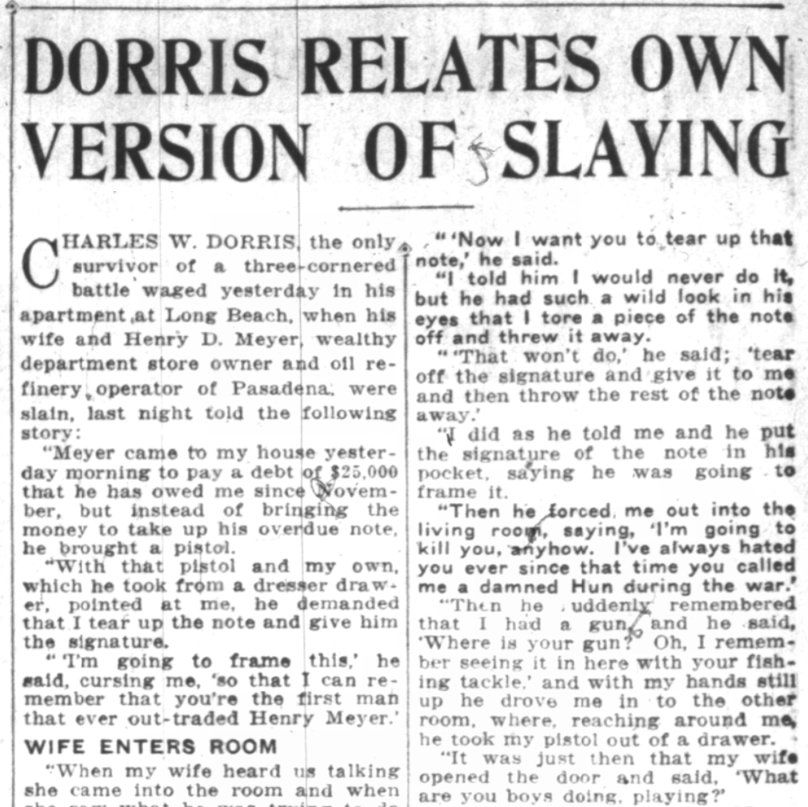

This article reports:

Charles W. Dorris, the only survivor of a three-cornered battle waged yesterday in his apartment at Long Beach, when his wife and Henry D. Meyer, wealthy department store owner and oil refinery operator of Pasadena, were slain, last night told the following story:

“Meyer came to my house yesterday morning to pay a debt of $25,000 [$460,000 today] that he has owed me since November, but instead of bringing the money to take up his overdue [promissory] note, he brought a pistol.

“With that pistol and my own, which he took from a dresser drawer, pointed at me, he demanded that I tear up the note and give him the signature.

“‘I’m going to frame this,’ he said, cursing at me, ‘so that I can remember that you’re the first man that ever out-traded Henry Meyer.’

“When my wife heard us talking she came into the room, and when she saw what he was trying to do she tried to get between us. He turned and killed her and then I grappled with him. I was holding both his wrists with the guns above our heads when he kicked me in the groin. I almost fell to the floor and as I did so I pulled his hands down. The guns were both pointed at his own breast when he pulled the triggers.

“I never shot him. He shot himself, after killing my wife.”

Investigators found discrepancies in Charlie’s story.

This article reports:

The two bullets that brought about the death Monday of Henry [D.] Meyer, wealthy Pasadena merchant and oil refinery operator, in the home of Charles W. Dorris at Long Beach, when Mrs. Dorris, too, was slain, were not fired at close range, as Dorris had declared, Dr. Frank Webb, the autopsy surgeon, will attempt to show at the coroner’s inquest today…

Meyer’s death came after he had been shot twice through the chest, a bullet passing entirely through each side.

The holes in Meyer’s back show that the bullets came out from one-half to one inch lower than the level at which they entered the chest.

There were no powder burns upon the dead man’s chest, it was declared, or upon his clothing to indicate that he had been shot at close range, as Dorris had declared.

Confronted by this evidence yesterday, and with the discovery of another lead slug in the kitchen of the apartment where the double slaying took place, Dorris revamped his story of the killing, adding other features.

The first shot that struck Meyer was fired, he admitted, in the kitchen, where his revolver was kept in a dresser drawer.

With the explosion, Dorris said, Meyer relaxed his hold upon the revolver to a slight extent and cried out that he was hit. Then he renewed the struggle.

Mrs. Dorris already lay dead in the living room, according to Dorris’ revised story, shot through the head by the first bullet from the .38 caliber revolver.

The hand-to-hand battle, with Meyer in possession of both Dorris’ pistol and the .32 caliber one, the ownership of which is in doubt, was carried back to the living room and, Dorris said yesterday, it was when they stumbled and fell over Mrs. Dorris’ body that the second shot was fired into the left side of Meyer’s chest.

Dorris is said to have declared in his original story that Meyer shot himself twice simultaneously with a revolver gripped in either hand.

Detectives found, however, that the only bullet discharged from the .32 caliber revolver had gone through the ceiling and Doctor Webb is said to have discovered that both holes through the dead man’s chest were made by .38 caliber slugs.

Therese’s shooting, as explained by criminologist J. Clark Sellers in a Los Angeles Examiner article, also contradicted her husband’s story.

Detectives spoke to Gerald Walters, a former janitor at the apartment building, who said that Therese had been in “deadly fear” of her husband, prompting her to carry a .32-caliber revolver for protection. Others interviewed included former employees and tenants, who told of overhearing the Dorrises’ violent arguments and seeing Therese emerging from the apartment with “a conspicuous black eye.”

On 15 July 1924 a grand jury indicted Charlie Dorris on two counts of murder after hearing more than 30 witnesses testify. District Attorney Asa Keyes then announced he would seek the death penalty.

The case against Charlie Dorris went to trial on 4 August.

Gerald Walters testified he had once witnessed an argument between the two business partners. Meyer came to the apartment building, and Charlie asked Walters to follow them to the Dorris apartment. There, as the partners argued over the terms of a lease, Charlie sprang from his chair and attempted to pull a revolver from his pocket, but Walters managed to restrain him. Later, Charlie insisted that Walters never tell anyone about the incident. Yet, on cross-examination, the former janitor admitted that he left Dorris’s employ “under a cloud of suspicion” after misrepresenting the purpose of a $300 loan from an elderly resident at the apartment.

Bank official John L. Keyes testified to the authenticity of the $25,000 note and the torn signature found in Meyer’s pocket.

Charlie Dorris took the stand and repeated his account – though he added new details once again. He said that he had asked his would-be killer to allow him to hold a prayer book while being shot. Meyer, he said, agreed, and as the men went in search of the prayer book, Meyer remembered Charlie’s .38 caliber revolver and demanded it.

On 13 August 1924 the jury in the double murder trial acquitted Charles W. Dorris after a 25-minute deliberation.

In August 1925, Charlie Dorris sued Mabel Meyer as Henry Meyer’s estate administrator. He won a judgment for the $25,000 note, minus $800. The victory was short-lived.

On the night of 9 September 1925, as Charlie stepped from a streetcar in front of St. Vincent’s Hospital, he slipped and fell below the wheels which crushed both legs. Doctors determined that amputation was needed, yet his condition was too serious for immediate surgery. Surrounded by longtime friends, the 46-year-old lost consciousness and died at 12:25 a.m.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: “Investigating a Mystery.” Designed by Freepik (www.freepik.com)

Related Articles: