Introduction: In this article, Mary Harrell-Sesniak discusses the origins and meanings of various family surnames, and shows how including the origins of your family surnames in your genealogy research may reveal intriguing clues about your ancestry. Mary is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background.

Ever wonder about the origin of your family surname? If so, you are not alone.

Many people would like to learn about their family surname, but don’t know where to look for more information. Fortunately, historical and modern newspapers frequently have articles about last names. In addition, you can find out your last name meaning by tracing its roots.

Crispin’s French Origins

Many newspaper articles discuss the meaning of specific surnames, such as this 1871 piece on the surname Crispin. The patron saint of shoemakers was St. Crispin, which is derived from the French term “crepin,” which means a shoemaker’s last (mechanical form in the shape of a foot). (See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Last.)

Other historical newspaper articles discuss the etymology or nomenclature of surnames, which is the study of their origins. Where did particular names come from? How were they assigned? Is there a special meaning behind them? All of these are interesting components for your genealogical research and can lead to a deeper understanding of your familial roots.

The First English Surnames

This 1893 newspaper article reports that the first English surname was adopted in the reign of King Edward the Confessor of England, who ruled between 1042 and 1066. If correct, this first surname was probably for a nobleman and most likely established to carry on hereditary rights (titles, and later property).

This 1823 newspaper article also reports that surnames were first adopted in the 11th century in England, and “for the distinction of families in which they were to continue hereditary.”

The old news article notes that the term “surname” came not from the word “sire,” but from a French concept indicating a super-addendum (or additional name added to one’s religious or Christian name). Of course, surnames weren’t just required for Christians, but for every culture and religion.

Patronymics and Matronymics

As human populations grew, there needed to be a system to identify individuals. Each country chose their own method, and within a society, a religious group or individualized group, some might have chosen their own unique system.

One early naming identification method was to associate a son’s surname with a father’s first name, and a daughter’s with her mother’s.

This is known as patronymics and matronymics, and if you ever come across a person with just one name, this is called mononymics (usually associated with rulers or famous individuals). See Wikipedia’s article on patronymics: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patronymic.

A Look at Surnames around the World

Depending upon cultural customs, a specific spelling or pattern for the name was designated.

In most cases the surname was modified, but in some cases the name was constructed differently. In some parts of Asia for example, the surname is given first, rather than last—and in other places, another word is inserted to indicate the family relationship.

Hebrew: One culture where you will find examples of this practice of word insertion in names is with the Jews. Hebrew names are often expressed with the use of “ben,” meaning son of, or with “bint,” meaning daughter of.

Ireland: Watch for names such as Fitzgerald—the “fitz” indicates that someone was the son of Gerald. According to Behind the Name’s website, this particular surname came from the Anglo-Norman French and was introduced to Ireland at the time of William the Conqueror.

Netherlands: Dutch patronymics can carry on for several generations. The Dutch Wikipedia explanation is that a “Willem Peter Adriaan Jan Verschuren would be Willem, son of Peter, son of Adriaan, son of Jan Verschuren.”

Poland: A common way to express a son’s last name is by the use of “wicz” at the end. Correspondingly, “ówna” or “’anka” may be used for an unmarried daughter, and “owa” or “’ina” for a married woman or widow.

Wikipedia’s article at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polish_name gives the example of a man with the last name of Nowak. His unmarried daughter would use Nowakówna and his wife or widow would use Nowakowa.

If you encounter a name ending in “ski,” the person is a male. If you see “ska” at the end, the person is female. There are many other variations, including “wicz,” “owicz,” “ewicz,” and “ycz” which can be added to a name, along with diminutives (similar to calling someone “little” as a pet name). See About.com’s article at http://genealogy.about.com/cs/surname/a/polish_surnames.htm for more examples.

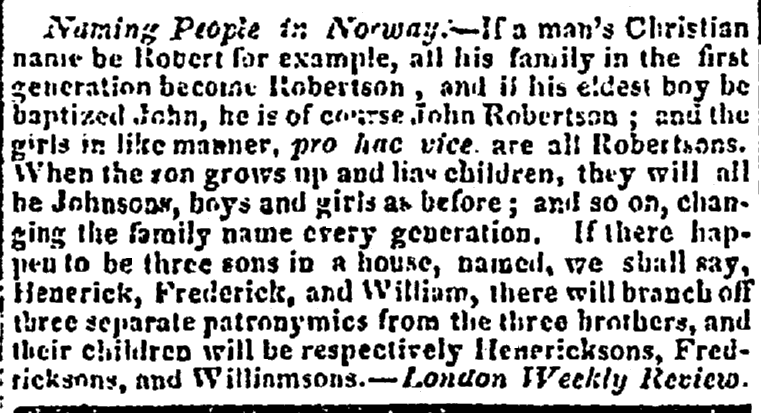

Scandinavia: “Son” or “dotter” or “dottir” is a common addition for boys and girls names, and there are slight spelling variations from country to country. Although most of Scandinavia no longer practices patronymics, you may still see it in Iceland.

Examples: a daughter of a man named Sven might use the surname Svensdottir, and Leif Ericson, the famous Norse explorer, has a name that identifies him as the son of an Eric (Erik the Red.) See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leif_Erikson.

Spain/Portugal: Although it doesn’t mean son, “ez” (Spain) and “es” (Portugal) are used to indicate males, such as with the names Gonzales or Hernandez. See the article on Spanish patronymics at http://spanishlinguist.us/2013/08/spanish-patronymics/.

Wales: Over time, there have been several variations of name usage in Wales. Sometimes you’ll find that the surnames of children were an unmodified version of the father’s name. A son Rees might be named James Rees. Another option related to the terms “ap” (son of) or “verch/ferch” (daughter of). The name Madog ap Rhys would be interpreted as Madog, the son of Rhys, and Maredudd ferch Rhys would be Maredudd, the daughter of Rhys.

To complicate matters, a name might indicate if a woman were the first or second wife of a man, or a widow.

For an in-depth explanation, see Tangwystyl verch Morgant Glasvryn’s article “Women’s Names in the First Half of 16th Century Wales (with particular attention to the surnames of married women).”

These are just some of the many types of matronyms and patronyms that you might find while researching your ancestry, so be sure to investigate your ancestral countries further.

Naming by Association (towns, physical attributes, etc.)

We can thank the practice of taxation for other methods of assigning surnames, some of which are attributed to the English poll taxes of 1377, 1379 and 1381.

See “The English Poll Taxes, 1377-1381” by George Redmonds, 28 March 2002, published online by American Ancestors.org at www.americanancestors.org/the-english-poll-taxes-1377-1381/.

In order to keep track of who owed what taxes, names were recorded on the tax rolls in a variety of ways. Some people were associated with their villages, others by trades or occupations; for example, Taylor last name origin comes from the occupational name for a tailor. In addition, others were associated by distinguishing features or attributes such as a very tall, or blind, man.

Most Common Surnames by Country

If you are stuck on the origins of your last name, consider the commonality of names in specific places.

Most of us are aware that Smith and Jones (Discover Jones last name origin!) are among the most familiar U.S. surnames, but what about other countries?

Wikipedia’s article List of the Most Common Surnames in Europe has an interesting list, some of which I’ve included below. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_the_most_common_surnames_in_Europe.

- Belgium: Peeters (meaning the rock, similar to Petros, Peterson, Peters, Perez)

- England: Smith (a tradesman)

- France: Martin

- Germany: Miller (Miller last name origin tied to occupational job title)

- Greece: Nagy (meaning great) or Papadopoulos

- Ireland: Murphy or Of Murchadh (a personal name meaning descendant of Murchadh or “sea hound/warrior”)

- Italy: Rossi and Russo (red-haired)

- Luxembourg: Schmit (blacksmith, metal worker, equivalent to Smith)

- Netherlands: De Jong (equivalent of Young)

- Northern Ireland: Wilson

- Norway: Hansen (son of Hans)

- Poland: Nowak (meaning new man)

- Scotland: Smith

- Spain: Garcia (means brave in battle)

- Sweden: Anderssen (son of Anders)

- Wales: Jones (Jones last name origin of Medieval English origins, derived from the given name John, which in turn is derived from the Hebrew name Yochanan/Johanan)

Genealogical Facts a Surname Might Reveal

Be sure to include the origins of your family surnames in your genealogy research, as they may reveal intriguing clues about your ancestry:

- Country of origin or hometown

- Occupation

- Parentage

- Physical and mental attributes

- Religion

An example in my own research is the surname Exton. This family came to America from Euxton, England, an obvious spelling variation. And my maiden name, Harrell, has Norman-French origins. Although a legend, Madame Marie Harel or Harrell is thought to have been the creator of Camembert Cheese in 1791. This is a family favorite of ours today, so perhaps there is a connection!

Genealogy Tip: don’t forget to consider spelling variations in your surname research. My earlier blog article Ancestral Name Searches: 4 Tips for Tracing Surname Spellings provides some examples of how names change over time.

Resources for Researching Surnames

- Behind the Name

- Federation of Family History Societies

- Guild of One-Name Studies: http://www.one-name.org/

- The Internet Surname Database: https://www.surnamedb.com/

- Russian Jewish Encyclopedia (from the Jewish Encyclopedia of Russia, or Rossiyskaya Evreiskaya Entsiclopediya, first edition, 1995, Moscow): http://www.jewishgen.org/belarus/rje_a.htm

Related Family Surname Research Articles

My name is Barrus but it has changed a number of times. One was Ba(r)row(e)- first immigrant to Mass/Plymouth Colony. I heard it could have been because he/they lived next to a barrow or hill. My mother-in-law’s maiden name was Burrows.