If your ancestor fought in the Civil War, does your family still have any of his letters? Some of the most moving accounts we have are the letters soldiers wrote to their loved ones during that great conflict. Even if one of your ancestor’s letters hasn’t been passed down in the family, there is still a chance you can find what he wrote – for many newspapers during the Civil War printed soldiers’ letters home.

When one of those letters was published by the writer’s home paper, the emotional response went beyond the soldier’s family to the greater community – Macon, Georgia, in the following example. This letter, simply titled “A Soldier’s Letter” in the newspaper, was written on this day 154 years ago – on 24 March 1862.

Here is a transcript of that letter:

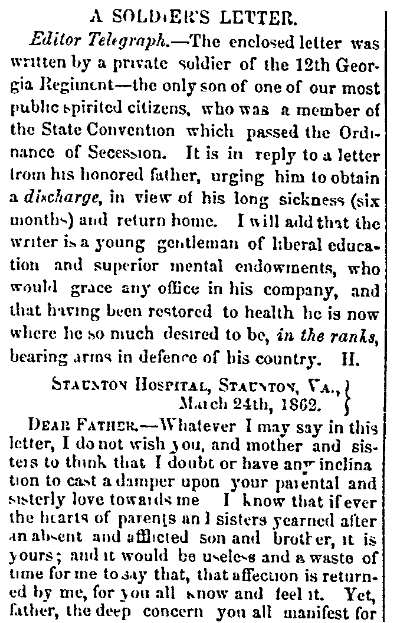

Editor Telegraph: The enclosed letter was written by a private soldier of the 12th Georgia Regiment – the only son of one of our most public-spirited citizens, who was a member of the State Convention which passed the Ordinance of Secession. It is in reply to a letter from his honored father, urging him to obtain a discharge, in view of his long sickness (six months) and return home. I will add that the writer is a young gentleman of liberal education and superior mental endowments, who would grace any office in his company, and that having been restored to health he is now where he so much desired to be, in the ranks, bearing arms in defence of his country. – H.

Staunton Hospital, Staunton, Va., March 24th, 1862

Dear Father: Whatever I may say in this letter, I do not wish you, and mother and sisters, to think that I doubt or have any inclination to cast a damper upon your parental and sisterly love towards me. I know that if ever the hearts of parents and sisters yearned after an absent and afflicted son and brother, it is yours; and it would be useless and a waste of time for me to say that, that affection is returned by me, for you all know and feel it. Yet, father, the deep concern you all manifest for me is too great, if I am to judge by your last letter, and also previous ones. I imagine that you all are grieving over my afflictions to such an extent that it has already made all of you low spirited. When you grieve for me and wish for my final return home, grieve first over the afflictions of our country, and pray for the return of peace and for our independence, and for the moral welfare of those who are now our enemies as well as for our own Southern people. Suppose I should die in the Hospital, would that be anything to the downfall of our country, or more than other fathers, mothers and sisters have had to befall their

[break in the letter]

…be so depressed in spirit, for in my hours of sadness and reflection, when I remember that the dearest ones on earth to me are also in my condition, it only tends to make my case the worse. Then cheer up, and look and pray to God, first for the protection and deliverance of our infant, yet great and powerful country, and then for my safe return home. Oh, father, mother and sisters, you should consider my case in all its bearings and not be blinded by the love and affection you have for me. As freely as I volunteered to fight the battles of my country with the assistance of my companions in arms, so freely do I now volunteer to fight disease and misfortunes, with my physicians and friends to assist me. And if it should please kind Providence to spare me, I can then look back and remember that, without a father to run back and forth after me, I worked my own way among strangers and in a strange country.

You insist that if my physicians offer me a certificate for a discharge, to accept it. In answer to that request, I must say that I cannot, so long as I know that any of them entertain a doubt of my PERMANENT disability. Whenever I go home on a discharge, I must go with a clear conscience. And although I feel my disability, yet, knowing that my physicians are the better judges, my conscience will not allow me to apply for a discharge. If I should come home with a discharge, you will not find me going again to war as a Lieutenant, Sergeant or Corporal, as some have done, for when I am disabled from duty as a private I shall also be unable to fill an officer’s place. And besides, it would show that I had got tired of a private’s life, and had, from some slight affliction, obtained a discharge, when I really did not need or deserve any.

Then let us be easy and cheerful, for all things are worked by the good Lord for the best, and if I do really deserve a discharge I shall get it.

We are compelled to trust the welfare of our country to the wisdom of the great and just God, and I know that you do it cheerfully. Then, can you not trust MY welfare and life in His hands, when I am as nought to the C.S., our own dear country? – D.

Search GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives to find some soldiers’ letters from the Civil War.

Related Civil War Articles:

- Civil War Genealogy: Old Letters in Newspapers & Research Resources

- Civil War Newspaper Research: Personal Notices & Letters

- Using Historical Newspapers to Research My Civil War Ancestry

- The ‘Confederate Column’ – a Times-Picayune Newspaper Feature

- Civil War Genealogy: How to Find Union Soldier Uniform Clues