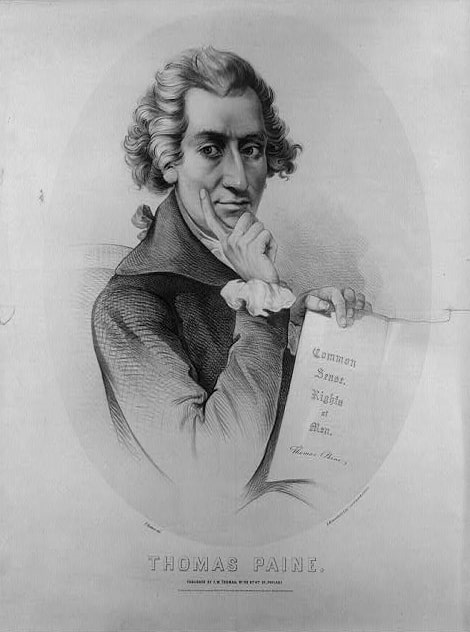

Introduction: In this article, Jane Hampton Cook describes how readers reacted to “Common Sense,” Thomas Paine’s incredibly popular pamphlet that helped persuade Americans to support the American Revolution. Jane is a presidential historian and author of ten books, including Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War. Her works can be found at Janecook.com. She is also the host of Red, White, Blue and You.

Recap: Yesterday’s Part I article covered the initial (anonymous) printing of Common Sense, Thomas Paine’s radical, 47-page pamphlet that became wildly popular and helped turn American attitudes toward Great Britain from hoped-for reconciliation to rebellion and outright revolution.

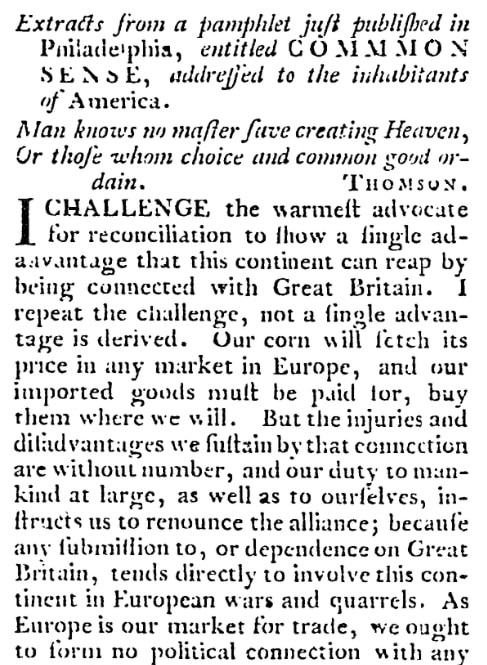

Common Sense became so popular so quickly (it was first printed in January 1776) that the Virginia Gazette published an extract of it in early February. In these passages, Paine put forward logical reasons for America to become independent of England, and thus to begin the world again.

The extract begins with this provocative statement:

“I challenge the warmest advocate for reconciliation to show a single advantage that this continent can reap by being connected with Great Britain. I repeat the challenge, not a single advantage is derived.”

Paine goes on to say:

“…any submission to, or dependence on Great Britain, tends directly to involve this continent in European wars and quarrels… Europe is too thickly planted with kingdoms to be long at peace; and whenever a war breaks out between England and any foreign power, the trade of America goes to ruin, because of her connection with Britain.

“…Everything that is right, or reasonable, pleads for separation. The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature, cries, It is time to part. Even the distance at which the Almighty hath placed England and America is a strong and natural proof that the authority of the one over the other was never the design of Heaven.”

Knowing that Bostonians were living under a lockdown imposed by the British military, Paine viewed the present state of America as precarious:

“But let our imaginations transport us for a few moments to Boston; that seat of wretchedness will teach us wisdom, and instruct us forever to renounce a power in whom we can have no trust. The inhabitants of that unfortunate city, who but a few months ago were in ease and affluence, have now no other alternative than to stay and starve, or turn out to beg; endangered by the fire of their friends if they continue in the city, and plundered by government if they leave it.”

Bostonians received Paine’s solution and New Year’s resolution (“We have it in our power to begin the world over again”) with glee.

In a letter Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John on 2 March 1776, she said:

“I am charmed with the sentiments of Common Sense; and wonder how an honest heart, one who wishes the welfare of their country, and the happiness of posterity, can hesitate one moment at adopting them.”

George Washington also agreed with Common Sense, especially because the British had burned Falmouth, Massachusetts, and Norfolk, Virginia. In a letter to Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Reed that Washington wrote on 31 January 1776, he said:

“A few more of such flaming arguments as were exhibited at Falmouth and Norfolk, added to the sound doctrine and unanswerable reasoning contained (in the pamphlet) Common Sense, will not leave numbers at a loss to decide upon the propriety of a separation.”

In another letter to Reed, written on 1 April 1776, Washington said:

“By private letters which I have lately received from Virginia, I find Common Sense is working a powerful change there in the minds of many men.”

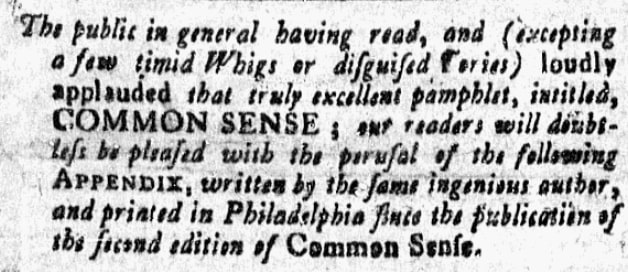

By March 1776 the conclusion was clear as more and more newspapers published extracts of Common Sense. Before publishing one such extract, the editors of the New England Chronicle, or Essex Gazette wrote:

They said:

“The public in general having read, and (excepting a few timid Whigs or disguised Tories) loudly applauded that truly excellent pamphlet, intitled, Common Sense; our readers will doubtless be pleased with the perusal of the following Appendix, written by the same ingenious author, and printed in Philadelphia since the publication of the second edition of Common Sense.”

Within months, Thomas Paine’s New Year’s resolution for America came true, as the Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1776.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Article: