In the early morning hours of 31 January 1968, over 80,000 combined Communist and Viet Cong troops surprised the Vietnamese army and its American allies by launching the Tet Offensive during what was supposed to be a cease-fire celebrating the Vietnamese lunar New Year. Around 100 cities and provinces throughout South Vietnam were simultaneously attacked with a coordinated force that surprised their adversaries.

Initially taken off-guard, the Vietnamese army and the Americans rallied to defeat the attacks after fierce fighting, in some cases in a day or two, in others only after a month-long battle. When the fighting ceased and the smoke cleared, the Communists and Viet Cong had lost 37,000 troops killed and many more wounded or captured. Though the Americans, by contrast, lost 2,500, the Tet Offensive was a victory for North Vietnam in that it seriously weakened public support for the war back in America.

The fighting that raged in many of the cities devastated entire neighborhoods, as the opposing forces battled block to block. A reporter was stationed in one such city, Ban Me Thuot, and described what he saw in this article.

Here is a transcription of this article:

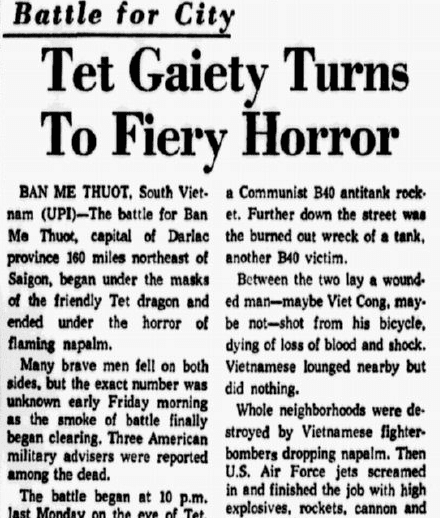

Battle for City

Tet Gaiety Turns to Fiery Horror

BAN ME THUOT, South Vietnam (UPI) – The battle for Ban Me Thuot, capital of Darlac province 160 miles northeast of Saigon, began under the masks of the friendly Tet dragon and ended under the horror of flaming napalm.

Many brave men fell on both sides, but the exact number was unknown early Friday morning as the smoke of battle finally began clearing. Three American military advisers were reported among the dead.

The battle began at 10 p.m. last Monday on the eve of Tet, the lunar new year.

Viet Cong terror teams infiltrating the Central Highlands city with hundreds of other guerrillas struck at the Ban Me Thuot police force. The attacks were partially muffled by thousands of Tet firecrackers.

Six policemen were killed in a matter of minutes. The assassins made a clean getaway.

Three hours later, at 1:35 a.m. on Tet morning, the Viet Cong struck in force.

Col. Henry A. Barder III of Waco, Texas, senior adviser to the Vietnamese 23rd Infantry Division stationed at Ban Me Thuot, estimated that 2,000 troops – both guerrillas and North Vietnamese regulars from the 233rd Regiment – were inside the city and all around it when the attack began.

The Viet Cong had managed to gain their positions despite the fact that 13 days before troops of the 23rd Division had captured an attack plan so detailed that one U.S. adviser described it as a “plan Napoleon might have written for one of his campaigns.”

The VC managed to do it despite battalion-sized screens the division commander, Col. Truong Quang An, had ordered north and south of the city.

When the main forces of the Viet Cong struck from all sides of the city, they had the help of others already inside Ban Me Thuot.

For the next three days, Ban Me Thuot was a battleground like the cities of World War II.

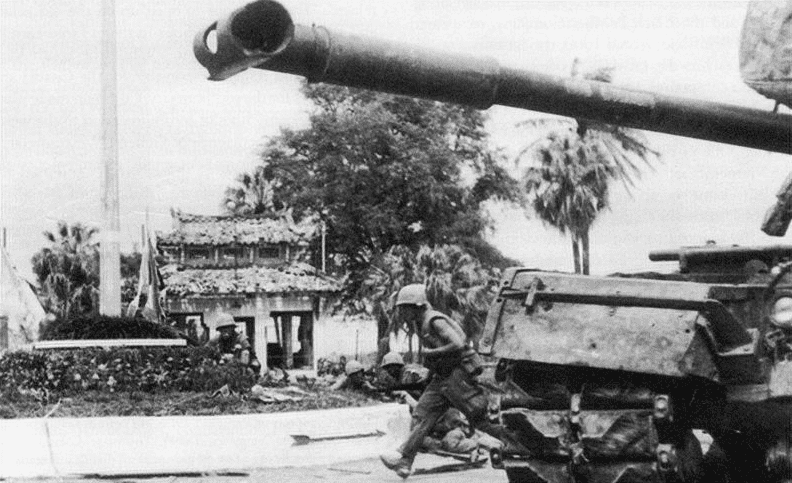

Tanks and armored personnel carriers fought from block to block, blasting away walls, houses, anything that stood in their way. Emperor Bao Dai’s palace was left a shambles.

A dead horse, three neat bullet holes stitched in his side and stomach, sprawled in the street. Another, a Montagnard pony no bigger than a Shetland, stood all day long with his head against the palace wall, turned from the tanks and the troops that lined the street, wounded and in shock.

Nearby, a Jeep ambulance lay on its side, the victim of a Communist B40 antitank rocket. Further down the street was the burned out wreck of a tank, another B40 victim.

Between the two lay a wounded man – maybe Viet Cong, maybe not – shot from his bicycle, dying of loss of blood and shock. Vietnamese lounged nearby but did nothing.

Whole neighborhoods were destroyed by Vietnamese fighter-bombers dropping napalm. Then U.S. Air Force jets screamed in and finished the job with high explosives, rockets, cannon and more napalm.

Many fell on both sides. No one, neither Col. Barder nor his Vietnamese counterpart, Col. An, knows exactly how many. No doubt, many more Viet Cong than Vietnamese. The Vietnamese had air and artillery on their side and they used it unsparingly by necessity.

They also had individual courage of high order.

Maj. Tran Van Tan, the commander of the battalion that screened the city to the south and did the major portion of the fighting outside the city, personally led his troops on assaults against fortified villages.

Tan’s counterpart, 1st Lt. Larry Stewart of Beaver Dam, Ky., said he “had to run to keep up with him.” Stewart, an Army officer, said the 45-year-old major killed three Viet Cong himself, one at 100 yards distance and two at 20 yards.

Maj. James R. Brooks of Wilmington, N.C., senior adviser to the commander of the 45th Infantry Regiment, came out of battle full of praise for his “ruff-puffs,” the regional forces and popular forces that are always underpaid, underequipped and underrated.

“Boy, they really fought,” Brooks said.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your family serve in the Vietnam War? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Wasn’t there a Special Forces compound that didn’t get overrun?

I’m not sure, Glenn. Perhaps one of our veteran readers can help us out with your question.