After 24 months and 17 days of secret, difficult negotiations – during a war that lasted 37 months – an armistice was signed on 27 July 1953, finally halting the fighting in the Korean War. A bloody, destructive proxy war in the Cold War struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union, the Korean War caused millions of military and civilian casualties. More than 36,000 U.S. troops died during the conflict.

After all the fighting and dying, the border remained unchanged: the armistice left the two Koreas divided at the 38th parallel, just as they had been when the war began. Today, a 2.5-mile-wide demilitarized zone separates North and South Korea, with sporadic incidents of trespass and violence leaving the entire area in a perpetual state of mistrust and anxiety.

The war began when Communist troops from North Korea invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950. What began as a civil war became an international conflict when the superpowers and their allies became involved. Eventually, the Korean War pitted the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea), the People’s Republic of China, and the Soviet Union against the Republic of Korea (South Korea), the United States, and 15 United Nations allies.

Three years and a month of fighting produced approximately 2 million combat casualties. In addition, civilian populations both in the North and South suffered horribly, often as a result of massacres and starvation. The final tally will never be known, but it is estimated there were as many as 2.5 million civilian casualties during the Korean War.

In America, the conflict in Korea was officially a “police action” because Congress never declared war. However unofficial, the war in Korea took a heavy toll on American troops: 36,516 died and 92,134 were wounded. The armistice finally ending the fighting was only that – a ceasefire – not a permanent peace treaty, and today the Korean peninsula remains one of the world’s hot spots for potential war.

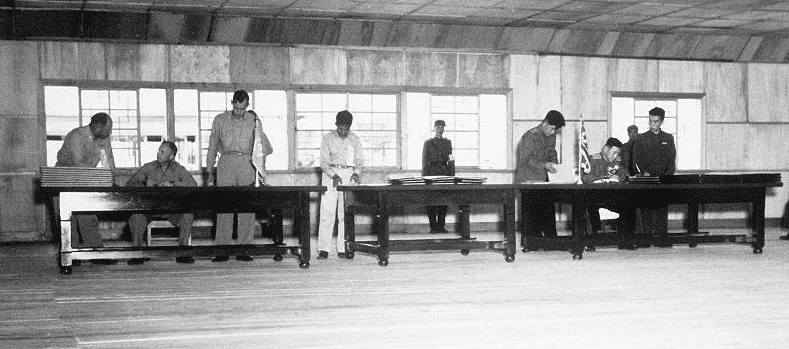

As explained in the newspaper article below, the ten-minute armistice ceremony reflected the war itself: cold, grim, and filled with mistrust.

Here is a transcription of this article:

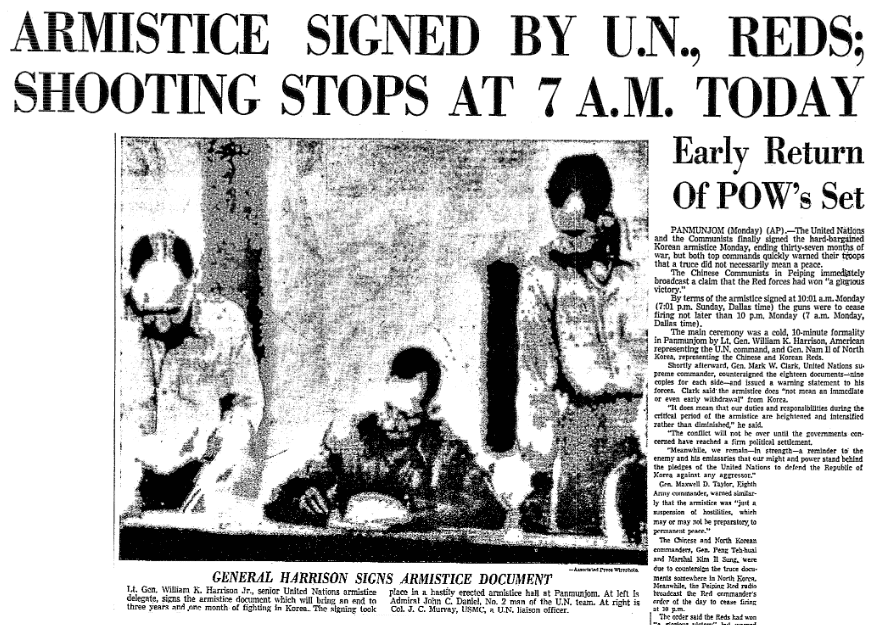

Armistice Signed by U.N., Reds;

Shooting Stops at 7 A.M. Today

Early Return of POWs Set

Panmunjom (Monday) (AP) – The United Nations and the Communists finally signed the hard-bargained Korean armistice Monday, ending thirty-seven months of war, but both top commands quickly warned their troops that a truce did not necessarily mean a peace.

The Chinese Communists in Peiping immediately broadcast a claim that the Red forces had won “a glorious victory.”

By terms of the armistice signed at 10:01 a.m. Monday (7:01 p.m. Sunday, Dallas time) the guns were to cease firing not later than 10 p.m. Monday (7 a.m. Monday, Dallas time).

The main ceremony was a cold, 10-minute formality in Panmunjom by Lt. Gen. William K. Harrison, American representing the U.N. command, and Gen. Nam Il of North Korea, representing the Chinese and Korean Reds.

Shortly afterward, Gen. Mark W. Clark, United Nations supreme commander, countersigned the eighteen documents – nine copies for each side – and issued a warning statement to his forces. Clark said the armistice does “not mean an immediate or even early withdrawal” from Korea.

“It does mean that our duties and responsibilities during the critical period of the armistice are heightened and intensified rather than diminished,” he said.

“The conflict will not be over until the governments concerned have reached a firm political settlement.

“Meanwhile, we remain – in strength – a reminder to the enemy and his emissaries that our might and power stand behind the pledges of the United Nations to defend the Republic of Korea against any aggressor.”

Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, Eighth Army commander, warned similarly that the armistice was “just a suspension of hostilities, which may or may not be preparatory to permanent peace.”

The Chinese and North Korean commanders, Gen. Peng Teh-huai and Marshal Kim Il Sung, were due to countersign the truce documents somewhere in North Korea. Meanwhile, the Peiping Red radio broadcast the Red commander’s order of the day to cease firing at 10 p.m.

The order said the Reds had won “a glorious victory” but warned them to “guard against aggressive and disruptive actions from the other side.”

Ignoring the North Korean invasion of the South on June 25, 1950, and the Chinese intervention Oct. 25, 1950, the Communist order of the day said the Red troops had fought heroically “for three years against aggression and in defense of peace.”

The formal signing ceremony by Harrison and Nam Il was a cold and silent one in this hamlet near the thirty-eighth parallel, where the war began and near which the stalemated armies have been locked for two years past.

They met in a jerry-built but ornate structure with an Oriental pagoda roof in this war-ruined wayside village of Panmunjom which the Koreans called, “The inn with the wooden door.”

They began at 10:01 a.m. (7:01 p.m. Dallas time, Sunday) and finished exactly ten minutes later. They separated in silence, but not before exchanging one long, searching look.

Three hours later, at 1:01 p.m. (10:01 p.m. Dallas time, Sunday), General Clark signed at the Allied advance headquarters in Munsan and sent the copies off to North Korea.

The Red chiefs, Chinese General Peng and North Korean Marshal Kim, were to send their signed copies down to Clark. These were anticlimactic signatures.

Unable to agree on meeting at Panmunjom, the top commanders had agreed that Harrison and Nam Il would do the signing that set the armistice in motion.

The strokes of their pens on the eighteen copies of the armistice document touched off reactions around the world, from the hilly battlefields of Korea where troops have fought in mud and dust and snow, to the world capitals where diplomats have pondered the Korean crisis and what to do about it.

President Eisenhower in a radio-television address to the American people from Washington hailed the armistice with thanksgiving. He declared the United Nations had met the challenge of aggression with “deeds of decision” and warned that the United States and its allies must remain vigilant.

Marshal Kim in a broadcast to his troops ordered the firing to cease at 10 p.m.

In New York, Lester B. Pearson of Canada, president of the U.N. General Assembly, said the Assembly would meet Aug. 17 to consider plans for a Korean political conference.

Before that conference is convened to work on the tremendous problems wrapped up in the future of a Korea divided and fought over by the Communist and free worlds, other events decreed by the armistice must come to pass.

The fighting men of Communist China and Korea on one side and South Korea, the United States and fifteen other allied nations on the other must pull back from the cease-fire line, leaving a demilitarized buffer zone 2½ miles wide across the Korean peninsula.

Along their new line they must dig in and wait while others decide whether the armistice will resolve into permanent peace.

The prisoners of war – all who want to go home – must be exchanged at this historic little mud-hut village where the armistice was signed. These include about 3,500 Americans, 8,000 South Koreans and about 1,000 from other allied nations. The exchange should start within the week.

Prisoners who refuse repatriation – there are about 14,500 Chinese and 8,000 North Koreans – will be given explanations by countrymen designed to allay their fears. Then if they still resist after 90 days the political conference will be handed the problem.

That’s one more tough nut for the conference, and if it can not crack it in thirty days, the prisoners will be released to civilian status in South Korea, with the right to go to neutral countries of their choice.

Representatives of four neutral nations – Sweden, Switzerland, Poland and Czechoslovakia – are charged with observing the armistice. A fifth, India, will join these four in supervising prisoners who resist repatriation, and India will supply guards.

President Syngman Rhee of South Korea declared after the signing that the Republic of Korea would not disturb the truce for “a limited time” while a political conference attempts to liberate and unify Korea.

Rhee wants a unified Korea, and may decide to fight for it if the conference can not realize his ambition.

These are the vistas opened and the burdens summoned by the armistice which was signed Monday.

Newsreel and television cameras hummed steadily and still cameras clicked at intervals throughout the ceremony.

Combined radio networks broadcast a description of the momentous ceremony.

A Communist newsman asked Harrison outside the signing hall, “Any comment?”

“You know I don’t do that,” Harrison replied.

Thus drew to a close the stalemated conflict which the United States and the United Nations entered as a “police action” against Communist aggression.

Within three days to a week prisoners will begin to flow homeward.

The momentous announcement that the United Nations command and the Communists had agreed to a cease-fire after two years, seventeen days of negotiations was made in Tokyo Sunday night by General Clark.

An official allied spokesman said the record of the months of secret negotiations would not be made public until after the armistice is signed.

No representative of South Korean President Syngman Rhee was expected to witness the signing of a truce which leaves Korea divided.

Pyun Yung-Tai, Rhee’s fiery Republic of Korea foreign minister, promised in a statement that neither the ROK people nor the army will revolt against an armistice “at this time.”

But Pyun reiterated to newsmen the conditional ROK stand that it had promised the United States not to oppose a truce only until the post-armistice political conference has had ninety days to unify Korea.

The United States has assured the Reds it is imposing no such time limit.

Clark indicated the ordeal of 12,000 Red-held war prisoners – 2,938 Americans, 8,000 Koreans and about 1,000 from other allied nations – will end in a few days.

He told a reporter if the Reds cooperate prisoner exchange may begin within a week or sooner and the first freed Americans will be home in from two to three weeks.

Even after the announcement that agreement had been reached on a cease fire, small Communist units attacked Allied outposts on the western front, but were repulsed, the United States Eighth Army reported. The Red attacks came after the Communists momentarily stepped up artillery and mortar shelling.

Allied warplanes bombed as usual, while the battleship New Jersey bombarded Wonsan, the east coast Red port battered by two and one-half years of shelling.

Allied air and ground commanders were given orders empowering them to do whatever necessary to minimize casualties in the final, delicate hours of the war.

United States Eighth Army division commands had permission to use their own judgment on offensive action, with the general intent of not forcing action on the Reds unless they asked for it. Secret orders, presumably along the same lines, were issued to the United States Fifth Air Force.

Other sealed orders, presumably for after the cease fire, were given Allied troop commanders.

As of last Wednesday, 24,965 Americans had died in the three-year war. Another 13,285 were missing and 103,760, including 2,392 who later died, were wounded.

For the Allies the human cost was 72,000 killed in combat, 270,000 wounded, 84,000 captured or missing. Red losses were estimated at 1,400,000.

“I hope the end of hostilities will foreshadow the beginning of a peace for the world as well as for ravished Korea,” Clark said, in announcing the agreement.

He warned that “a long and difficult road still lies ahead, and there are no shortcuts.”

The U.N. commander issued his statement en route to Korea from Tokyo.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did anyone in your family serve in the Korean War? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.