So many Americans have fought and died to found and preserve our nation’s freedom.

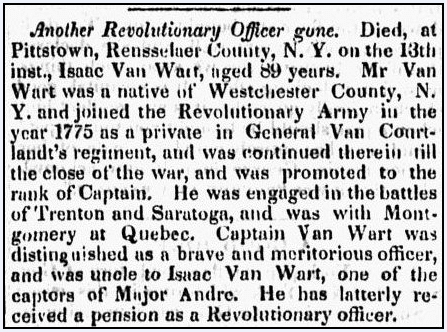

It often comes as a surprise to genealogists to discover that newspapers reported—in detail—about the lives of the men who fought in the American Revolutionary War.

Estimates are that 92,000 Americans and French troops fought 314,000 British troops, Hessian troops and loyalists. Of that number 25,000 Americans died in the war and an estimated 25,000 more were wounded.

Once again David beat Goliath.

Our ancestors fought and won their independence from Britain…and we want to know their stories.

Militia lists, bounty land warrants and town monuments document their names, but it is often in newspapers that we find their personal stories.

Newspapers tell us about their life before, during and after the Revolutionary War.

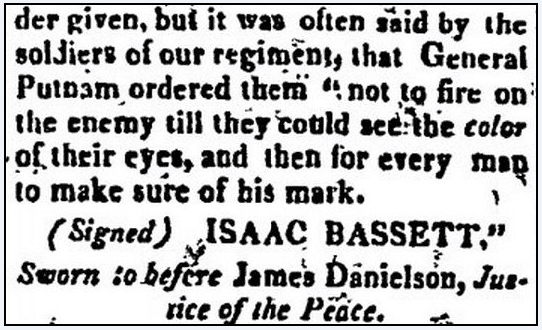

Newspapers tell us gripping Revolutionary War stories like this one of Isaac Bassett and the men in his regiment who were told “not to fire on the enemy till they could see the [whites] of their eyes…”

These words have been passed down to us for over 200 years.

Newspapers let us personalize these stories to our own families.

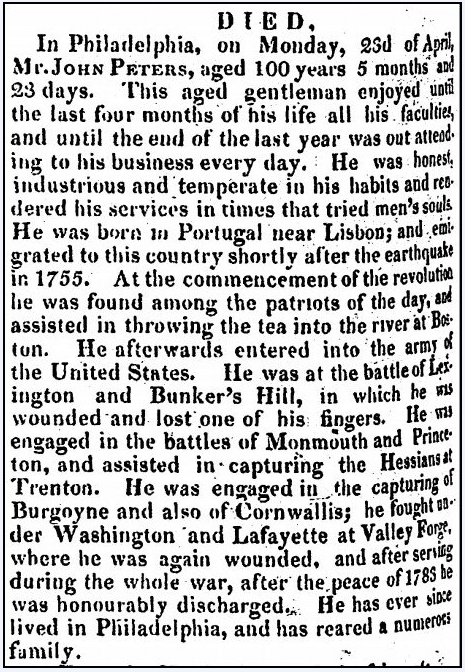

And newspapers can tell us the unexpected details of their lives. Like this obituary of John Peters, who died at age 100 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1832.

And newspapers can tell us the unexpected details of their lives. Like this obituary of John Peters, who died at age 100 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1832.

With a name like John Peters it would be easy to assume that he was born in America or England, causing us to spend years looking for his birthplace in those countries.

Searching through the usual Revolutionary War records we might not ever find it mentioned that “He was born in Portugal near Lisbon” or that he immigrated “to this country shortly after the earthquake in 1755,” but his newspaper obituary provides this information.

Wow—that was an unexpected genealogy find.

This patriot’s 1800s obituary is filled with details about his life, his character and his service to the nation. From throwing tea into Boston Harbor to fighting in many of the most famous Revolutionary War battles – these are exactly the details we need to understand who he was and what he was like—and the information pointing us to where he was born.

As we think about Memorial Day, July 4th and documenting the lives of our ancestors, it is essential that we uncover every newspaper article—every fact and every clue—so that we can accurately record their information and preserve and permanently pass down their stories for future generations.

Onward.

I have seen this claim that it was “the color of their eyes” not “the whites of their eyes” popping up in more places, including in textbooks. Your reference to the Boston Centinel piece from 1818 seems to be the only place that it is found other than in a couple modern souvenir books. It seems clear that even the “whites of their eyes” statement may very well be myth, but are you aware of any evidence that it was “color of their eyes” other than this newspaper account 44 years after the fact?

I can’t seem to find any evidence either way, nor have I found any significant discussion of this in mainstream papers or books.

Also, most seem to indicate it was either William Prescott who said the famous line or that there is no way of knowing who said it. Other than your quote from the Centinel I had never seen it clearly stated that Putnam said it. In your opinion, would this quote based on hearsay so long after the battle be sufficient to determine that Putnam said the line and that it was “color” not “white?”

Thank you.

In your opinion, would this quote based on hearsay so long after the battle be sufficient to determine that Putnam said the line and that it was “color” not “white?”

SJW: OK, in my opinion this is accurate. Here is what the article is saying “…it was often said by the soldiers of our regiment, that General Putnam ordered them…”

This quote was memorable and passed down by the members of his regiment. Isaac Bassett was giving testimony of this in a court case and his statement was sworn before a Justice of the Peace. Clearly the memory of those events was fixed in their minds.

But consider this. It’s memorable – catchy.

Did other commanders pick up that phrase to encourage their troops?

Here is what Wikipedia has to say on this:

“The famous order “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes” was popularized in stories about the battle of Bunker Hill. It is uncertain as to who said it there, since various histories, including eyewitness accounts,[79] attribute it to Putnam, Stark, Prescott, or Gridley, and it may have been said first by one, and repeated by the others. It was also not an original statement. The idea dates originally to the general-king Gustavus Adolphus (1594 – 1632) who gave standing orders to his musketeers: “never to give fire, till they could see their own image in the pupil of their enemy’s eye”.[80] Gustavus Adolphus’s military teachings were widely admired and imitated and caused this saying to be often repeated. It was used by General James Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham, when his troops defeated Montcalm’s army on September 13, 1759.[81][page needed] The earliest similar quote came from the Battle of Dettingen on June 27, 1743, where Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Andrew Agnew of Lochnaw warned his Regiment, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, not to fire until they could “see the white of their e’en.”[82] The phrase was also used by Prince Charles of Prussia in 1745, and repeated in 1755 by Frederick the Great, and may have been mentioned in histories the colonial military leaders were familiar with.[83] Whether or not it was actually said in this battle, it was clear that the colonial military leadership were regularly reminding their troops to hold their fire until the moment when it would have the greatest effect, especially in situations where their ammunition would be limited. [84]

79. Lewis, John E., ed. The Mammoth Book of How it Happened. London: Robinson, 1998. Print. P. 179

80. Joannis Schefferi, “Memorabilium Sueticae Gentis Exemplorum Liber Singularis” (1671) p. 42

81. R. Reilly, “The Rest to Fortune: The Life of Major-General James Wolfe” (1960)

82. Anderson, p. 679

83. Winsor, p. 85

84. French, pp. 269–270

See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Bunker_Hill