Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry writes about another aspect of Puritan life in the 17th century Massachusetts Bay Colony. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

In the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the 17th century, adultery and out-of-wedlock sex were by far the most prosecuted crimes. For this reason, the midwife’s role in legal proceedings was just as crucial as it was in birthing the babies. In 1986 the Associated Press covered this subject to promote Roger Thompson book’s Sex in Middlesex: Popular Mores in a Massachusetts County, 1649-1699.

Thompson researched court and town records covering a period of 50 years, in the area north and west of Boston, Massachusetts. His findings revealed that “for 17th century Massachusetts women, child-support payments were fairly easy to obtain,” and women wielded more power and “potent legal recourse, and had to use it more often than modern Americans might realize.”

The colonial midwife proved to be an essential worker for the courts and provided a great service for a community that did not want a swarm of illegitimate children on the town dole.

As this article reported:

“Puritan society, wishing to ensure that the community would not have to pay for an illegitimate child’s upbringing, and that the sinners who indulged in such [sexual] relations repented, was anxious to identify the father as well as the expectant mother.”

The number of cases of unwed mothers was staggering. By 1668 the law gave women, especially midwives, important powers.

According to the article:

“One cry from a woman giving birth was enough evidence to condemn a colonial Massachusetts man of fornication and sentence him to a lifetime of payments and possibly a public whipping and fines.”

The grand inquisitors would refuse to help a woman in labor unless she named the father. This system was effective, and I will cite many of those cases in a later story. However, Thompson cited one paternity case where the mother refused to deliver the name of her fellow fornicator and triggered a major court drama.

In January 1696 Susannah Colburn*, a single woman, gave birth to a baby boy. When her midwife tried to ferret out the daddy’s name, Susannah replied: “I must perish, for I do not know.” She was afraid to disclose the father’s name because it was the son of her midwife. The case is complicated and had many twists and turns.

According to records, Susannah was an orphan. Her father, Edward Coburn Jr., was killed at the Siege of Brookfield in 1675 during King Philip’s War. I could not find a birth record for Susannah, and her father never married. She was living in the home of Samuel and Sarah (Langton) Varnum. Sarah was her midwife, and the son alleged to be the child’s father was John, age 27.

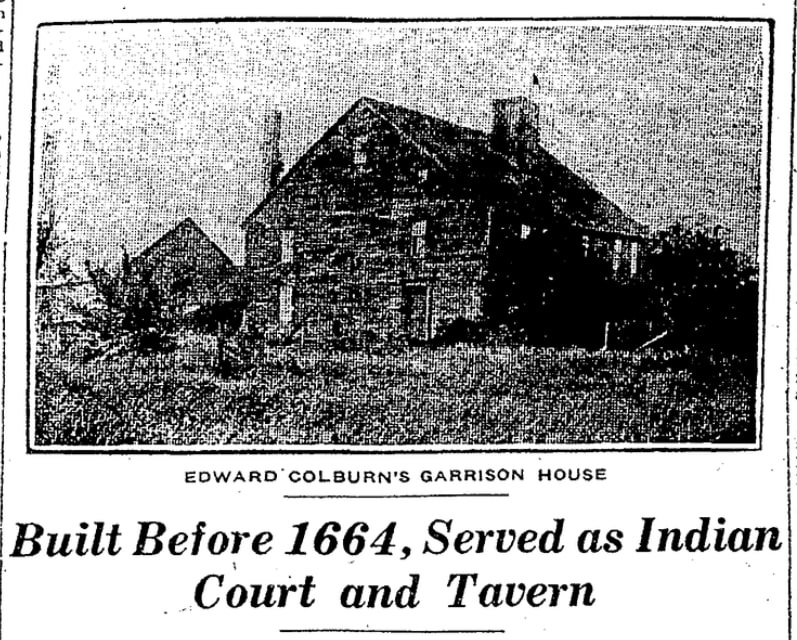

Both the Colburn and Varnum families were prominent members of the community. A 1923 Boston Herald article featured the historic garrison house purchased by Edward Colburn Sr. from James Webb. Edward and his wife Hannah Rolfe with their eight children, along with Samuel Varnum’s family – all of Ipswich – became the first permanent settlers of Dracut.

This article mentioned the death of Susannah’s father.

The lines intermarried and there still are numerous descendants today. Unfortunately, Susannah and her son John are not documented after this court case and they do not appear in Genealogy of the Descendants of Edward Colburn authored by descendant Silas R. Colburn.

According to Thompson’s book, the Varnum family used threats, sympathy, and persuasion with Susannah in their campaign to clear John’s name. Susannah had few friends to come forward on her behalf to counter the battery of depositions made by the Varnum family.

Some of the Colburn family were called in to testify. Among them was Hannah (Varnum) Colburn, daughter of Samuel and Sarah Varnum, who was married to Susannah’s uncle Ezra Colburn.

According to Thompson, Hannah testified:

“I asked her [Susannah] why she did not rise, and she replied ‘O aunt I have not hart to rise. I am a great sinner, nobody will endure me.’ Asked who is the father, she answered ‘If it would save my life, I can not tell you who is the father of my child,’ and wept bitterly.”

Stay tuned for more on the Colburn-Varnum paternity case.

*Various spellings: Coburn, Corborne, Colborne, and the variant used widely today, Colburn.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

My 8th great grandmother, Sarah Osgood, accused Thomas Sargent of fathering her child, Elizabeth Sargent (born October 1668). Thomas Sargent had married Rachael Barnes in Salisbury on 2 March 1667/8. He was found not guilty. Someplace (but I can’t find it at the current time) I have copied more of the record that said something like there was reason for suspicion but no proof. Was he found not guilty because he was newly married or was it because he was from a prominent family?

He might not be my 8th great grandfather via Elizabeth Sargent, but he is my 7th great grandfather via his son Jacob Sargent. Both of these are on my maternal grandmother’s side.

Thomas Sargent, b. Salisbury 11 June 1643; m. Salisbury 2 March 1667/8 Rachael Barnes. (Found not guilty of fathering Sarah Osgood’s child, October 1668 [EQC 4:64].)*

*Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts, 1636-1686, 9 volumes (Salem 1911-1975)

Dorothy, thanks for sharing! I have a story I am working on from the Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County, Massachusetts. It has many of the old Newbury and Salisbury lines. And yes, it seems like the prominent families received a lesser sentence and usually had to just pay a fine. Your ancestor’s story is similar to this, but the Varnum/Colburn case was sad as Susannah did not have the money or the support. Stay tuned!

It sounds like the male gender had it easy compared with the female gender. What happened to a woman who “snitched” on the father? If the scarlet letter is historically accurate, the women had a far gloomier future than the men did.

Carol, thanks for sharing. I am going to provide more examples of the males getting off easy. Stay tuned!

I have an ancestor that I am working on that falls in this category. She used the father’s surname as the surname of the illegitimate child. So your article helps me understand why she would have done that.

Thank you Diane, and I am glad to hear it gave you more understanding in tracing your own ancestors. There are many cases I am finding that a mother will not marry the paternal father, but the surname of the birth father is given to the illegitimate child. More cases coming!