By the summer of 1862 President Abraham Lincoln and the Union were growing impatient for some progress toward the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. Lincoln’s hopes had been high the previous summer, but then a 35,000-man Union army under General Irvin McDowell was routed at the Civil War’s first major engagement, the First Battle of Bull Run (Manassas), on 21 July 1861. Lincoln then appointed a new man, General George Brinton McClellan, to capture Richmond.

However, McClellan turned out to be just as disappointing as McDowell; his huge 90,000-man Army of the Potomac was driven from the outskirts of Richmond by the new Confederate commander, Robert E. Lee, during the Seven Days Battles the last week of June 1862.

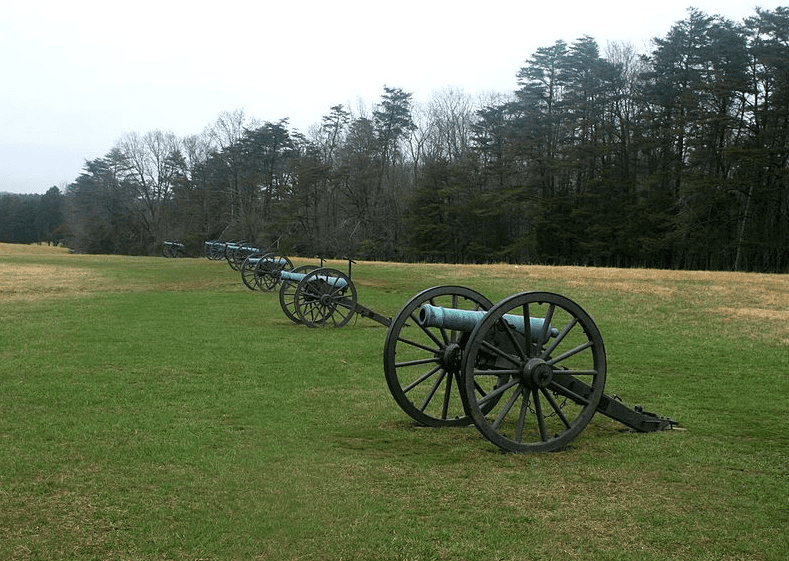

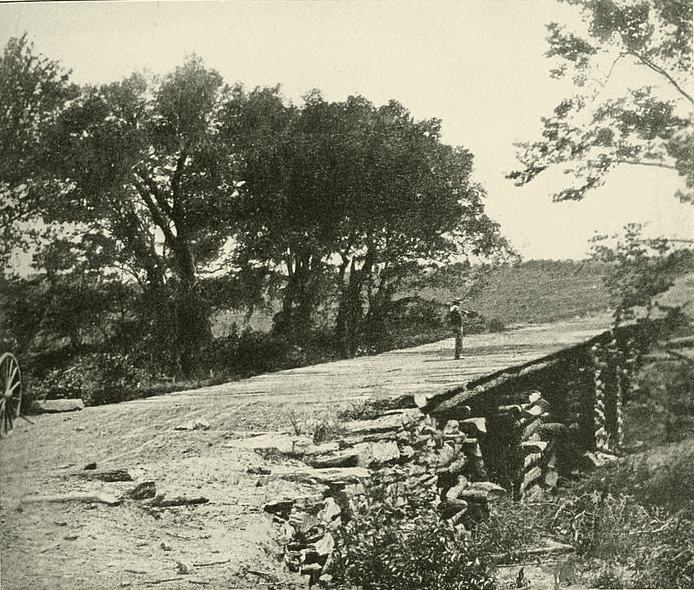

Now Lincoln’s hopes rested in a new commander, General John Pope, and his 62,000-man Army of Virginia. In three days of fierce fighting, 28-30 Aug. 1862, on the same ground as the previous summer’s clash, Lee and the Confederacy won another major victory: the Second Battle of Bull Run (Manassas).

Though he had the larger army, Pope managed to lose this battle because he became fixated on surrounding half of the Confederate army, 24,000 men led by General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson – and stubbornly refused to acknowledge that the other half of the Southern forces, 30,000 men led by General James Longstreet, was poised on his left ready to smash his flank.

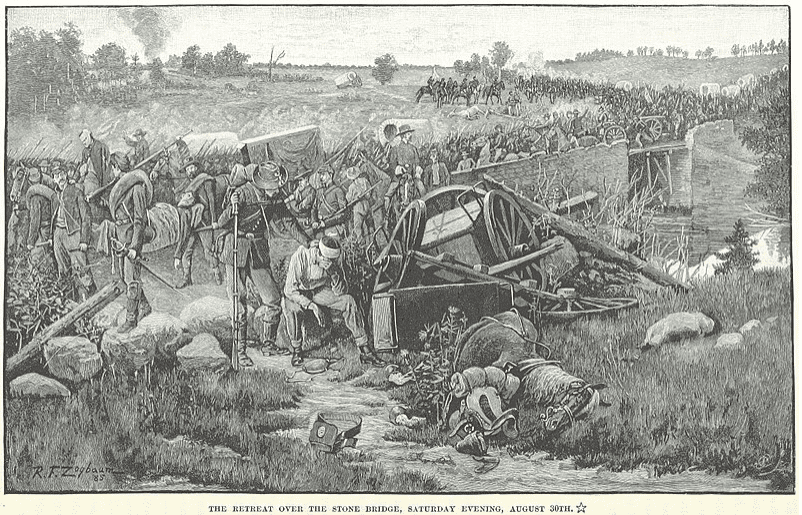

Pope’s astonishing incompetence played exactly into Lee’s plans, and when Longstreet’s men suddenly attacked the Union army on August 30 the Northern defeat was assured. Pope’s army was forced to retreat having suffered more than 10,000 casualties during the three days’ fighting. Though he lost 8,300 casualties himself, Lee’s triumph left him in a position to seize the offensive, and he promptly decided to carry the war to the North by invading Maryland. Lincoln relieved Pope of his command on 12 Sept. 1862.

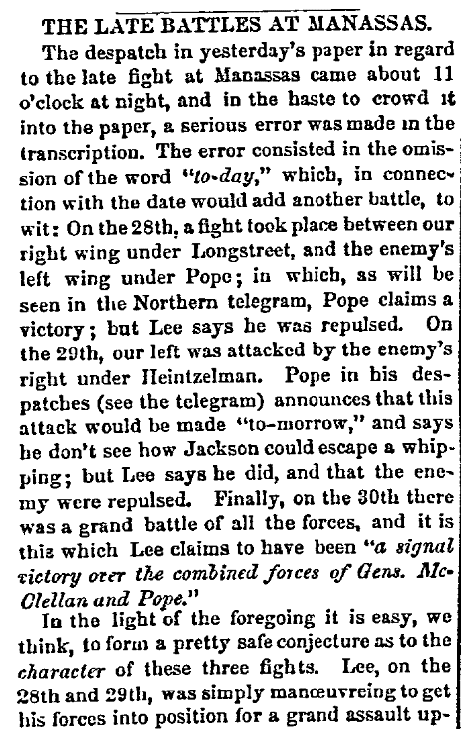

The following newspaper article is how anxious readers in Georgia learned of the stunning Confederate victory at Manassas.

Here is a transcription of this article:

THE LATE BATTLES AT MANASSAS.

The dispatch in yesterday’s paper in regard to the late fight at Manassas came about 11 o’clock at night, and in the haste to crowd it into the paper, a serious error was made in the transcription. The error consisted in the omission of the word “to-day,” which, in connection with the date would add another battle, to wit: On the 28th, a fight took place between our right wing under Longstreet [correction: the attack involved Jackson’s forces – ed.], and the enemy’s left wing under Pope; in which, as will be seen in the Northern telegram, Pope claims a victory; but Lee says he was repulsed. On the 29th, our left was attacked by the enemy’s right under Heintzelman. Pope in his dispatches (see the telegram) announces that this attack would be made “tomorrow,” and says he don’t [sic] see how Jackson could escape a whipping; but Lee says he did, and that the enemy were repulsed. Finally, on the 30th there was a grand battle of all the forces, and it is this which Lee claims to have been “a signal victory over the combined forces of Gens. McClellan and Pope.”

In the light of the foregoing it is easy, we think, to form a pretty safe conjecture as to the character of these three fights. Lee, on the 28th and 29th, was simply maneuvering to get his forces into position for a grand assault upon the enemy. Their attacks on those days were probably designed to checkmate these movements – a design which failed. Pope possibly may have captured some prisoners, but he is so utterly untrustworthy that nobody can believe a word he says. The statement of Gen. Lee that both these attacks of the enemy were “repulsed” can leave no doubt upon the mind of anyone having a knowledge of the extremely cautious and truthful character of that great man.

Thus, then, the enemy’s attacks of the 28th and 29th, being foiled, and all of Lee’s dispositions completed, on the 30th the grand attack was made on our side, and the signal victory achieved. Now, whether all of McClellan’s forces had effected a junction with Pope, or whether allusion is here made only to the two divisions which we well know had succeeded in effecting this junction, we are unable to decide. If all of McClellan’s and Burnside’s armies had joined Pope, then the ideas of the position of the belligerents which we had gleaned from the Richmond papers are altogether erroneous. That junction must have been effected by way of the Potomac, between which and Pope’s army we had supposed our lines to extend all the way down to the neighborhood of the Rappahannock. On the other hand, look again at the telegram about Pope’s official dispatch, and it will be seen, Jackson was said to be six miles west of Centreville – a position which exactly corresponds with the previous representations of the Richmond press, and shows that we were then between the enemy and Manassas Junction and the Potomac.

How, then, could McClellan and Burnside, from Fredericksburg, have joined Pope, unless they cut their way through our lines, which is not probable? We are inclined, therefore, to believe that the expression in Gen. Lee’s dispatch, “combined forces of McClellan and Pope,” refers only to the two divisions of McClellan’s army which we know had joined Pope, and that McClellan and Burnside are still at Fredericksburg, or, at least, had not been able to effect the junction. This supposition is also sustained by the fact that in the Northern telegram alluded to, no mention is made of McClellan. Pope is in command of one wing and Heintzelman of the other – which would hardly have been the arrangement if McClellan had joined them.

It is however clear, from the Northern dispatches, that Jackson is between the enemy and Alexandria, and that is a great comfort – to us, we mean – not to him.

We shall suspend all glorification over this great victory till we hear all about it. We are grateful to God and happy over the result, but it is not a whit more than we all looked for and confidently anticipated.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in the Civil War? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Articles: