Has there ever been a more bizarre criminal case than newspaper heiress, socialite, and convicted bank robber Patty Hearst? Born to great wealth, the granddaughter of the famous newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, Patricia Campbell Hearst was violently taken from her life of enjoying good wines, antique shopping, and studying art when, as a 19-year-old college student, she was abducted from her apartment near the University of California at Berkeley campus on 4 February 1974.

Her kidnappers were armed terrorists from a revolutionary group calling itself the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA).

Two months after this trauma, Hearst was photographed participating in an armed bank robbery by the SLA on April 15. Then, on 18 September 1975 – just 19 months after her kidnapping – she was arrested after spending more than a year on the FBI’s “Most Wanted List.”

At her trial, the defense argued that Hearst was a victim of the “Stockholm syndrome,” in which hostages end up liking and even supporting their captors. The prosecution argued that she deliberately renounced her parents and her upbringing, and willingly joined a terrorist organization bent on violent revolution. The jury agreed with the prosecutors and Hearst was found guilty of bank robbery on 20 March 1976 and sentenced to 35 years in jail.

Later, however, her sentence was lessened to 7 years – and she ended up only serving 22 months when President Jimmy Carter commuted her sentence. She was released on 1 February 1979. As the last act of his presidency, Bill Clinton granted Patty Hearst a full pardon on 20 January 2001.

The following two newspaper articles are about this strange case of Patty Hearst. The first article reports on her arrest in San Francisco, and the second article recounts some of the noteworthy aspects and statements of her brief criminal career.

Here is a transcription of this article:

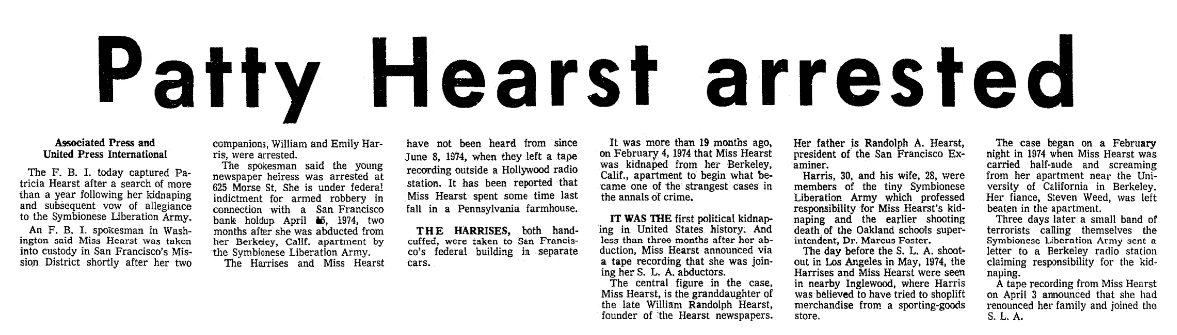

Patty Hearst arrested

Associated Press and United Press International

The F. B. I. today captured Patricia Hearst after a search of more than a year following her kidnapping and subsequent vow of allegiance to the Symbionese Liberation Army.

An F. B. I. spokesman in Washington said Miss Hearst was taken into custody in San Francisco’s Mission District shortly after her two companions, William and Emily Harris, were arrested.

The spokesman said the young newspaper heiress was arrested at 625 Morse St. She is under federal indictment for armed robbery in connection with a San Francisco bank holdup April 15, 1974, two months after she was abducted from her Berkeley, Calif., apartment by the Symbionese Liberation Army.

The Harrises and Miss Hearst have not been heard from since June 8, 1974, when they left a tape recording outside a Hollywood radio station. It has been reported that Miss Hearst spent some time last fall in a Pennsylvania farmhouse.

The Harrises, both handcuffed, were taken to San Francisco’s federal building in separate cars.

It was more than 19 months ago, on February 4, 1974, that Miss Hearst was kidnapped from her Berkeley, Calif., apartment to begin what became one of the strangest cases in the annals of crime.

It was the first political kidnapping in United States history. And less than three months after her abduction, Miss Hearst announced via a tape recording that she was joining her S. L. A. abductors.

The central figure in the case, Miss Hearst, is the granddaughter of the late William Randolph Hearst, founder of the Hearst newspapers.

Her father is Randolph A. Hearst, president of the San Francisco Examiner.

Harris, 30, and his wife, 28, were members of the tiny Symbionese Liberation Army which professed responsibility for Miss Hearst’s kidnapping and the earlier shooting death of the Oakland schools superintendent, Dr. Marcus Foster.

The day before the S. L. A. shootout in Los Angeles in May 1974, the Harrises and Miss Hearst were seen in nearby Inglewood, where Harris was believed to have tried to shoplift merchandise from a sporting-goods store.

The case began on a February night in 1974 when Miss Hearst was carried half-nude and screaming from her apartment near the University of California in Berkeley. Her fiancé, Steven Weed, was left beaten in the apartment.

Three days later a small band of terrorists calling themselves the Symbionese Liberation Army sent a letter to a Berkeley radio station claiming responsibility for the kidnapping.

A tape recording from Miss Hearst on April 3 announced that she had renounced her family and joined the S. L. A.

Here is a transcription of this article:

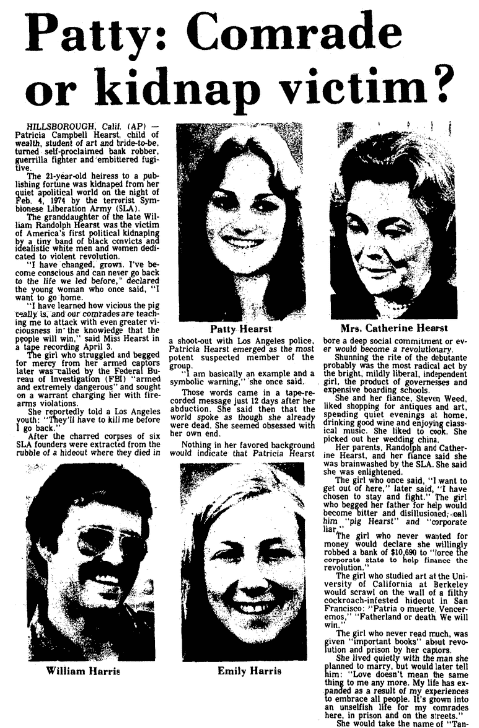

Patty: Comrade or kidnap victim?

HILLSBOROUGH, Calif. (AP) – Patricia Campbell Hearst, child of wealth, student of art and bride-to-be, turned self-proclaimed bank robber, guerrilla fighter and embittered fugitive.

The 21-year-old heiress to a publishing fortune was kidnapped from her quiet apolitical world on the night of Feb. 4, 1974, by the terrorist Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA).

The granddaughter of the late William Randolph Hearst was the victim of America’s first political kidnapping by a tiny band of black convicts and idealistic white men and women dedicated to violent revolution.

“I have changed, grown. I’ve become conscious and can never go back to the life we led before,” declared the young woman who once said, “I want to go home.”

“I have learned how vicious the pig really is, and our comrades are teaching me to attack with even greater viciousness in the knowledge that the people will win,” said Miss Hearst in a tape recording April 3.

The girl who struggled and begged for mercy from her armed captors later was called by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) “armed and extremely dangerous” and sought on a warrant charging her with firearms violations.

She reportedly told a Los Angeles youth: “They’ll have to kill me before I go back.”

After the charred corpses of six SLA founders were extracted from the rubble of a hideout where they died in a shoot-out with Los Angeles police, Patricia Hearst emerged as the most potent suspected member of the group.

“I am basically an example and a symbolic warning,” she once said.

Those words came in a tape-recorded message just 12 days after her abduction. She said then that the world spoke as though she already were dead. She seemed obsessed with her own end.

Nothing in her favored background would indicate that Patricia Hearst bore a deep social commitment or ever would become a revolutionary.

Shunning the rite of the debutante probably was the most radical act by the bright, mildly liberal, independent girl, the product of governesses and expensive boarding schools.

She and her fiancé, Steven Weed, liked shopping for antiques and art, spending quiet evenings at home, drinking good wine and enjoying classical music. She liked to cook. She picked out her wedding china.

Her parents, Randolph and Catherine Hearst, and her fiancé said she was brainwashed by the SLA. She said she was enlightened.

The girl who once said, “I want to get out of here,” later said, “I have chosen to stay and fight.” The girl who begged her father for help would become bitter and disillusioned, call him “pig Hearst” and “corporate liar.”

The girl who never wanted for money would declare she willingly robbed a bank of $10,690 to “force the corporate state to help finance the revolution.”

The girl who studied art at the University of California at Berkeley would scrawl on the wall of a filthy cockroach-infested hideout in San Francisco: “Patria o muerte. Venceremos,” “Fatherland or death. We will win.”

The girl who never read much, was given “important books” about revolution and prison by her captors.

She lived quietly with the man she planned to marry, but would later tell him: “Love doesn’t mean the same thing to me anymore. My life has expanded as a result of my experiences to embrace all people. It’s grown into an unselfish life for my comrades here, in prison and on the streets.”

She would take the name of “Tania” after the German-Argentine mistress of slain revolutionary Che Guevara.

She was described by her friends as mature, sincere and quiet. After the SLA bank holdup, her stunned father said, “We’ve had her 20 years. They’ve had her 60 days, and I don’t believe she’s going to change her philosophy that quickly or that permanently.”

Weed said she knew nothing about the limitations of her family’s finances and took for gospel her captors’ statements that her father could tap a vast fortune if he really wanted her free.

In each taped communiqué, she grew increasingly disillusioned with her parents’ efforts to free her, including a $2 million food giveaway for the poor. The SLA had demanded a $6 million program, but her father said he could not afford it.

“I know that we have the money,” she told her father, and said bitterly, “I don’t believe you’re doing everything you can. You said it was out of your hands. What you should have said was that you wash your hands of it.”

In a March 10 tape recording, Patricia Hearst told her parents: “I really want to get out of here, and I really want to get home alive.” But she added: “I no longer seem to have any importance as a human being.”

The nation’s first political kidnapping began with a knock on the door of a townhouse apartment Feb. 4, 1974, near the University of California campus in Berkeley.

Its bizarre course was to lead the Hearsts through a succession of ordeals, with each new blow more incredible than the previous.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers, as well as more recent events.