History calls it the “Medicine Lodge Treaty,” but history does not always get the story exactly right. For one thing, it was not one treaty, but three. For another thing, calling it a treaty glosses over what actually took place: the United States exerting its will over a defeated people, forcing several Southern Plains tribes to give up their ancestral lands and their traditional way of life, exchanging both for a miserable existence on sparse reservations dependent on government handouts for subsistence.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

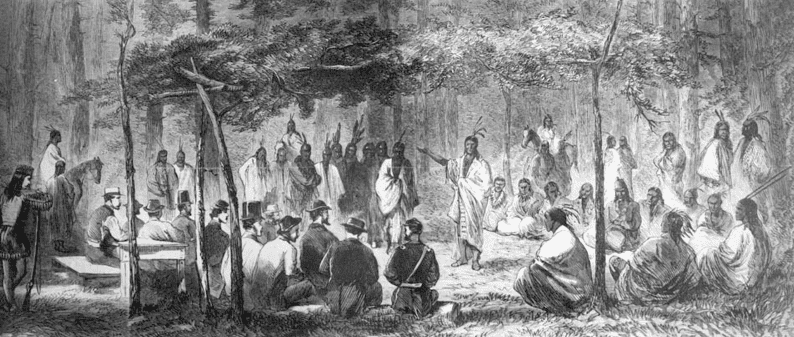

Tired of the cost and bloodshed of the wars with the Plains Indians, Congress established the Indian Peace Commission on 20 July 1867 to “negotiate” with the Indians to give up their land and lifestyle in exchange for reservation life in Oklahoma. These negotiations were sweetened with assurances of government support in the form of food and equipment, and tempered with the large force of U.S. troops and cavalry, as well as two menacing Gatling guns, that accompanied the Commission to each of its councils.

The military force was especially terrifying to the Indians – less than three years prior, a friendly camp of Cheyenne and Arapaho (primarily women and children) had been destroyed by Colonel John M. Chivington and 700 Colorado volunteer militia at the Sand Creek Massacre.

On 21 October 1867 the first two treaties were signed, one with the Comanche and Kiowa tribes, the second with the Plains Apaches. On October 28, the third treaty was signed, this with the Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne tribes. In each case, the tribes surrendered huge amounts of ancestral land for relatively small reservations on the parched plains of Oklahoma. All three treaties were signed at an Indian ceremonial site called Medicine Lodge Creek – hence the treaty’s name.

There is a bitter legacy to the Medicine Lodge Treaty. Its language stipulated that the treaty would only go into effect if approved by ¾ of the tribes’ adult males – that approval was never achieved. Therefore, the treaty was never legal, and eventually Kiowa Chief Lone Wolf sued the Interior Department, a case that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the 1903 Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock decision, the Court made one of the most lamentable decisions in its history, ruling that it did not matter if the tribes’ adult males did not approve the treaty because Indians were “wards of the nation” and, like the criminally insane, not capable of making decisions for themselves.

Along with its large military contingent, the Indian Peace Commission was also accompanied by a large press corps: eight newspaper correspondents attended the councils and recorded the work of the Commission. The following newspaper article is from one of those men, a correspondent from the Cincinnati Daily Gazette. His report, appalling to modern sensibilities, provides a fascinating glimpse into the scorn and hatred many whites felt toward Indians.

Sarcastically referring to the Indians as “the noble gods who infest the plains,” this reporter laments the fact that by resorting to negotiations, the Commission is forced to “crawl in acknowledgment of their nobility.” He is furious that revenge is not being exacted on “the murderers and ravishers” for “the hellish depredations committed by them.” At another point, he objects to the government supplying beef cattle to the hungry tribes, commenting “if the lazy Indians will not kill enough game to live on, they should not be prevented from starving.”

Here is a transcription of this article:

THE INDIAN COMMISSION.

The Southern-Four Thousand Indians.

A GENERAL COUNCIL TO BE HAD.

A Temporary Peace Probable.

Special Correspondence of the Cincinnati Gazette.

Medicine Lodge Creek,

Southwestern Kansas, October 14.

The Commission left Fort Harker on the morning of the 9th. General Augur, who was appointed to fill the place of General Sherman as one of the Commissioners, had not yet arrived. Governor S. J. Crawford, of Kansas, and Senator Ross, were invited, and came along as guests. The weather was pleasant, and the rolling plains were dry. Nothing of importance occurred on the way to Fort Larned, which distance was called from fifty to eighty miles, and we were three days between the two places. At Larned, on the 12th, we met Satan-ta, the Chief to whom General Hancock and other officers gave a full uniform, and who, a few days later, run the stock off from Fort Dodge. He was “heap glad” to see the “Big Chiefs” of the Commission, and gave them each a savage hug, which all the men who think more of an Indian than they do of a white man enjoyed hugely. Little Raven, of the Kiowas, fat and saucy, laid upon his back, the Commissioners passing forward, laying their venerable heads upon his heaving bosom, and thus resignedly accepting the situation. Other lesser Chiefs were there, and all of them very kindly submitted to an affilial hug from each of the men who represent the “miserable whites,” and who crave to do honor to the noble gods who infest the plains.

…Half-past ten, and we started southward. One hundred and fifty cavalry, and one hundred and thirty infantry made up the escort. Four Major Generals, one United States Senator, two Commissioners, twenty-four clerks and attaches (twelve more than are needed), nine guests, and eight correspondents, constitute the unfortunate men who are here to look at the scalps of our fellow-countrymen in the belts of those up to whom we must crawl in acknowledgment of their nobility. No questions are asked them concerning the hellish depredations committed by them. They must be paid for their crimes, and those who have been murdered and ravished must be censured for outraging the rights of the Indian. I do not find fault with the Commission in that which it contemplates doing, but they should do more. Before giving them large reservations, the murderers and ravishers should be demanded, and not one plug of tobacco given them until the demand is obeyed. But this is not proposed by the Commission; on the other hand no demands are to be made, and as little as possible must be said about the past. Those of the Commission (or some of them) have cousins and friends who trade and deal with the Indians, knowing that they have sufficient knowledge of the Indian and white man’s character, that they are white men, and having no lives or liberties at stake, it is very probable that they are interested with said cousins and friends, or perhaps they want to be. The Commission is here with free power over the military, agents, Indians and “other things.” The whole Commission must act, else the action is illegal. When on the trip up the Missouri, Commissioner Taylor and Gen. Sanborn concluded that a contract for eight hundred beef cattle must be let to feed the Indians we are now among. They had not seen these Indians at that time. The Commission knew nothing of the intention of the two gentlemen, but when, on the 12th, we came to Larned, an advertisement was seen which, apparently, was authorized by the Commission. The Commission, as a whole, knowing nothing of it, was surprised that such a step had been taken. Inquiry found that the two men had thought of these Indians, and being ambitious to control the movement and reap all the glory, if any is attached to it, made the advertisement in the name of the Commission. It is illegal as it stands, and the Commission should leave it so. By giving out such a contract the grossest injustice would be exercised against the Government. Thousands and tens of thousands of buffalo are roaming through this whole country, and if the lazy Indians will not kill enough game to live on, they should not be prevented from starving. Buffalo is not the only game they have; antelope, deer, elk, wild turkeys, prairie chickens and all kinds of game without number are in the timber, along the streams and on the green and fertile plains. If “our cousins” would live in civilization where rascality is not respected, the injustice of this, both to Indians and the Government, would be recognized soon by them.

Where Are We?

Here in the Indian village known as Medicine Creek Lodge, where the Cheyennes, Kiowas, Comanches and Arapahos have gathered to meet the Commission, in that unsurveyed portion of Kansas, in the southern part of the State, on Medicine creek. Large and thrifty groves of timber, as fertile lands as the world has seen and innumerable springs of water make this the prettiest and most desirable country west of the Missouri river. It does not belong to the Indians, but the Commission will, I suppose, give it to them if they ask for it. These Indians claim it by right of conquest from the Pawnees, but by treaty with the Government they gave it up and accepted the Smoky Hill country. Afterward, by treaty, they gave up the Smoky Hill country with the promise of the Government that this country should be given them. The Senate refused to ratify the treaty, and when the Indians were homeless by the broken promise of the Government, the Overland Mail and Union Pacific Railroad were built through the lands ceded in lieu of this country. The Dog Soldiers of the Cheyennes made war because of this wrong done them by the government, and do not give, as a cause of war, the burning of Pawnee Fork village by Gen. Hancock. But the Commission will endeavor to make them believe that the destruction of the village was a just cause [for compensation], so that they may injure Gen. Hancock, and thereby get a beef contract for “our cousins and friends.”

Profound Knowledge

Col. Tappan, who has a cousin who is a sutler in this country, and who loves the Indians, is very desirous that the Commission may buy up the crimes of the Indians and give protection to the frontiersman, without asking of the Indians any reasons or causes why they have made war. He is very properly censuring that useless, causeless and brutal affair, the Chivington massacre, and understands well the objects of Chivington in that cowardly act; is a bitter enemy of Chivington, but knows nothing concerning other Indian troubles, and is a useless member of the Commission. Gen. Sanborn, who shed tears over the fallen Indian, prefers Indian testimony to that of the white man, and from the beef question and other extreme thoughtless and careless acts, it is believed that he will labor faithfully to gain name and honor, at the same time not forgetting the almighty dollar. Men who have read Indian romances and Indian love stories are illy prepared to decide what should be done by those whose lives and property are endangered, the interests of whose State are retarded, and whose wives and daughters are being ravished daily by these savage devils, “the noble red men.”

Bull Bear, Chief of the Dog Soldiers of the Cheyennes, was in camp this morning, and says he will bring in the representative men of his bands. He is the man of the Cheyennes, and whatever step he and his bands take, the Cheyenne nation will accept. His people are now thirty miles from here making medicine, as they call it. This means that they are resupplying their stock of arrows and fixing up for the war, or for the winter hunting. There are about four thousand souls in this camp, including women and children. They are very much afraid of the troops, and tread about with the watchfulness of a hawk in search of a mouse. The counciling will begin tomorrow and will continue probably ten days.

–H. J. B.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Related Articles: