Was ever a Native American chief more ill-fated than Black Kettle, leader of the Southern Cheyenne? Black Kettle was a peace chief, convinced that the whites were far too powerful to resist; he told his followers their only hope was to give up fighting, accept harsh treaties, and submit to reservation life. It was his fate to have his peaceful camp betrayed twice by surprise attacks from vengeful whites, losing his people and eventually his own life, at the hands of such infamous Indian fighters as John M. Chivington and George Armstrong Custer.

In 1861 Black Kettle signed the Treaty of Fort Wise and moved his people to the Sand Creek Reservation in Colorado as instructed. He was given both a white flag of truce and an American flag, and told to fly both above his lodge to make clear that his was a peaceful village. Sadly, neither the promises of the commander of nearby Fort Lyon nor the flags provided any protection.

At dawn on 29 November 1864, Chivington led 700 Colorado volunteer militia in a ruthless attack on Black Kettle’s village. Chivington knew it was a peaceful Cheyenne camp, but the 100-day term of enlistment for his militia was about to expire without having encountered any hostile Indians, and Chivington desperately wanted a victory to boost his political aspirations. Chivington instructed his men to kill every Cheyenne they could find, even the children, snarling that “nits make lice.” Most of Black Kettle’s men were away on a hunting trip at the time of the attack, but that did not stop Chivington’s men. They slaughtered around 160 Indians that day, mostly women and children.

Although his wife was badly wounded, Black Kettle escaped the Sand Creek Massacre. Despite what his people had just suffered, he continued to believe that peace with the whites was the only hope for the Cheyenne. Less than three years later, he signed another harsh treaty in October 1867, the Medicine Lodge Treaty, which removed his people completely from their ancestral lands and relocated them to “Indian Territory,” present-day Oklahoma.

With no buffalo to hunt on their new reservation, the Cheyenne were completely cut off from their traditional way of life – and the land was not suitable for agriculture, making it impossible for them to do as the whites instructed and become “civilized” farmers. Some of Black Kettle’s young men began joining hostile Cheyenne, Arapaho and Kiowa warriors to raid white ranches and settlements in the summer of 1868, and the aging chief was powerless to stop them.

Famed Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman, now commander of the Military Division of the Missouri, ordered another famous Civil War veteran, General Philip Sheridan, to make war on the hostile Indians. (It was Sheridan who, in January 1869, uttered a phrase as notorious as Chivington’s “nits make lice” statement when he declared: “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead.”) Sherman and Sheridan turned to the services of a man they knew and trusted during the Civil War, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, to help subdue the hostile Cheyenne.

To survive the winter of 1868, Black Kettle moved his people to join a large encampment of Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa and Kiowa-Apache Indians along the Washita River near present-day Cheyenne, Oklahoma. Black Kettle still had around 250 followers in his camp, and the roughly 15-mile stretch of the Washita held winter camps totaling nearly 6,000 Native Americans.

Alarmed that his peaceful camp might be caught up in Sherman’s war against the hostile Indians, Black Kettle and other peace chiefs traveled to nearby Fort Cobb and met with Colonel William B. Hazen on 20 November 1868. Hazen evaded responsibility by saying he was not empowered to offer the four chiefs protection, insisting instead that they had to make peace with General Sheridan when he sent his forces against them. Receiving no satisfaction, the four chiefs left Fort Cobb and arrived back at their Washita camps the evening of November 26.

Black Kettle had no idea his world was about to be torn apart a second time.

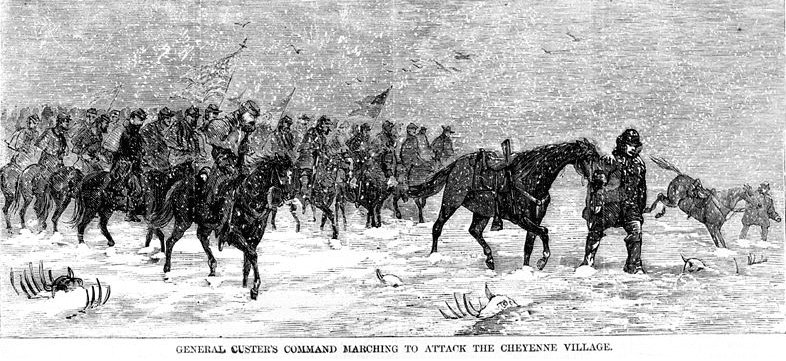

At dawn the next day, 27 November 1868, Custer led the 7th U.S. Cavalry in a swift attack against Black Kettle’s sleeping village. Taken completely by surprise, the Cheyenne were routed and their village destroyed, with the soldiers gunning down men, women and children. No accurate Native American casualty figures are available, with estimates ranging from a few dozen to more than 150 Indians killed. The soldiers suffered 21 killed and 13 wounded.

All the Cheyenne’s winter supply of meat, lodges and robes were burned, and around 700 Indian horses were rounded up and slaughtered. Black Kettle and his wife, Medicine Woman Later, were both shot in the back and killed while attempting to flee the attack. To prevent other Indians from camps along the Washita coming to Black Kettle’s aid, Custer captured 53 Cheyenne women and 3 children and forced them to ride among his solders, acting as human shields to prevent the Indian reinforcements from firing.

Custer immediately reported his “victory” to his superiors, claiming his men had killed 103 hostile Cheyenne warriors, with a few accidental deaths to some women and children. Many in the press hailed him as a hero, as shown in the first two of the following newspaper articles. However, word soon leaked out that many of the victims of Custer’s attack were women and children, and that it was Black Kettle’s camp – peaceful, not hostile, Indians – that Custer had destroyed. Reaction began to turn against Custer, as shown in the third newspaper article below.

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Indian War – Battle of General Custer with the Savages – Defeat of the Indians and Destruction of Their Villages – Casualties, &c.

WASHINGTON, December 2. – The report of General Sheridan is dated North Canadian River, at the junction of Beaver Creek, Indian Territory, via Fort Hays, November 29th, and is addressed to General Nichols, General Sherman’s adjutant at St. Louis, and is as follows:

GENERAL: I have the honor to report, for the information of the Lieutenant General, the following operations of General Custer’s command. On Nov. 23d I ordered him to proceed with eleven companies of his regiment of the Seventh Cavalry in a southerly direction towards the Antelope Hills, in search of hostile Indians. On the 26th he struck the trail of a war party of Black Kettle’s band returning from the north, near where the eastern line of the Panhandle of Texas crosses the main Canadian. He at once corralled his wagons and followed in pursuit to the headwaters of the Washita, thence down that stream, and on the morning of the 27th surprised the camp of Black Kettle, and after a desperate fight, in which Black Kettle was assisted by the Arapahoes under Little Raven, and the Kiowas under Satanta, captured the entire camp, killing the chief, Black Kettle, and one hundred and two Indian warriors, whose bodies were left on the field; all their stock, ammunition, arms, lodges, robes, and 53 women and three children. Our loss was Major Elliott, Captain Hamilton, and 19 enlisted men killed. Brevet Colonel Barnitz was badly wounded. Brevet Lieutenant Colonel T. W. Custer, Second Lieutenant E. J. March and 11 enlisted men wounded. Little Raven’s band of Arapahoes and Satanta’s band of Kiowas were encamped six miles below Black Kettle’s camp. About 800 or 900 animals captured were shot; the balance kept for military purposes. The highest credit is due General Custer and his command. They started in a furious storm, and traveled all the while in snow about 12 inches deep. Black Kettle’s and Little Raven’s families are among the prisoners. It was Black Kettle’s band who committed the first depredation on the Saline and Solomon rivers in Kansas.

The Kansas regiment has just come in. They missed the trail and had to straggle in the snowstorm, the horses suffering much in flesh, and the men living on buffalo meat and other game for eight days. If we can get one or two more good blows there will be no more Indian troubles in my department. We will be pinched in our ability to supply, and nature will present many difficulties in our winter operations, but we have stout hearts, and will do our best.

Two white children were recaptured. One white woman and one boy ten years old were brutally murdered by the Indian women when the attack commenced.

P. H. Sheridan,

Major General Commanding.

Note: the following editorial praising Custer and ridiculing those who sought peace with the Indians was published by the Patriot (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) on Dec. 5, 1868. Note that this article admiringly declares that Custer’s victory at the Washita “was a greater massacre than that of Chivington four years ago” at Sand Creek.

Here is a transcription of this article:

“LO! THE POOR INDIAN.”

The scream of the locomotive starts the wild buffalo herds as the Pacific railroad hastens in its completion to the Pacific, and the army marches to protect from the more savage Indian the emigrant and the traveler as they push to the farthest bounds of civilization. The missions of the Peace Commissioners, Indian agents, trappers and traders have done their best or their worst. Time pressed, the savages would not yield to mild means, and it need occasion no surprise if a stern policy should be exercised towards him. The recent reports from the seat of war show that the victory of General Custer at the headwaters of the Washita, over the Cheyennes, assisted by some warriors of the Kiowas, Sioux and Arapahoes, was complete and decisive. The death of their famous leader “Black Kettle” and of one hundred and fifty warriors, the capture of their wives and children, of their horses to the amount of one thousand, of their stock, their ammunition and implements of war, attest to the extent of the victory. It was a greater massacre than that of Chivington four years ago.

While the philanthropist mourns over the fate of the dusky sons of the forest, which, it seems, must soon close in the complete extermination of the race, yet the demands of westward marching civilization are inexorable. If the red man will not bend to the mild yoke of civilization, he must be broken. If he will not, like his more tractable half-cousin of the South, accept the bauble of the ballot, he must be disposed of by the bullet. Such a grand enterprise as the Pacific railroad in which the whole civilized world is interested, must not be halted for slow negotiation with the treacherous nomads of the plains. Since they have obstinately refused to accept in good faith the reservations marked out for them, and settle down to the arts of peaceful life, they have little to expect from such men as Sheridan and Custer. The undying repugnance of the Indian to the restraints of civilization and his implacable hatred of the white man will no longer be treated with the forbearance and indolence which have hitherto marked his treatment. More intelligent than the negro, he has had intercourse with the whites frequently enough to mark well the contrast between his barbarous manners and wild habits of life, and the laws of civilization; so that his deadly hostility to the “pale faces” and his relentless cruelty to the unhappy women and children who fall into his hands cannot be attributed to a brutal want of sense. He cunningly meets his white brother in council, makes big speech about the Great Father, lulls him to security, and soon after all the border is lighted by the flames of a savage war which spares neither [age] nor sex. To secure the commerce of the world which is making a great pathway from ocean to ocean, as well as to protect the lives of the frontiersman, there seems no other effective means than to oppose to the dripping tomahawk and scalping knife of the savage, the irresistible weapons of civilization. Since forbearance in the person of the mild missionary has ceased to be a virtue, let the man of peace yield to General Custer.

Note: this article shows the tide beginning to turn against Custer. It was published by the Daily Albany Argus on the front page.

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Late Victory over the Indians – Was It a Massacre?

The officers report of the details of the battle of the Washita in the Indian Territory, on the 27th of November last, which resulted, as we are informed, in the triumphant victory of Brevet Major General George A. Custer over Black Kettle’s band of Cheyennes, has recently been published. In this report is a list of our officers and men killed and wounded, and of the Indian chiefs destroyed, Black Kettle being of the number.

The report gives a glowing account of the attack upon the Indians before the dawn of day, while they were asleep in their tents, unmindful of danger and of the terrible havoc that followed. It also, with fine dramatic effect, enters into the particulars of the return of the victors to their camp, bearing in the dead and wounded women and children who had been conquered in the fight: “one squaw in the left knee”; “one squaw in the left hip”; “one squaw in the right breast, and ranging upwards through the lower jaw”; “one boy in the left thigh”; “one girl in the right side”; “one girl in the left forearm.” The report states that “everyone was more than anxious to see the victors of the Washita, and it was with considerable impatience the appearance of the column was looked for.” The band reiterated the stirring tones of “Garry Owen.” “Next came General Custer riding alone, mounted on a magnificent black stallion, and dressed in a short blue sack coat, trimmed with the color of his arm of the service, and reinforced with fur collar and cuffs; on his head he wore an otter cap.” “When General Custer came within fifty yards of the commanding General he left his position in the column and dashed up to his chief, when a warm and hearty exchange of salutations was made between the commander and his distinguished lieutenant.” “Next followed the living evidence of the victory, over fifty squaws and their children, surrounded by a suitable guard to prevent their escape.” “Without a sign, without a glance to the right or left, these remnants of the band of the once powerful Black Kettle followed with all the submission of captives.”

This splendid victory, as the sequel now clearly proves, was achieved over an innocent, confiding and friendly tribe of Indians, at peace with us, and asleep in their tents at night, when the attack was made. We quote from the New York Herald Washington correspondence of Dec. 29th:

ANOTHER VERSION OF GENERAL CUSTER’S INDIAN BATTLE.

Thomas Murphy, Superintendent of the Central Indian Department, arrived in the city this morning. From the statements made by Mr. Murphy in connection with the late attack by General Custer on the Cheyenne and Arapahoe Indians on the Washita River there is very little doubt that another fearful blunder was in that case committed by our military commanders.

In the summer of 1867, when the Peace Commissioners were in the Indian Country, they had made arrangements to meet a number of chiefs at Fort Kearney, and Superintendent Murphy had represented to them that some of the more important chiefs of the disaffected tribes could be gotten together at a point some miles further in the interior. They deputed Murphy to go there and meet the Indians he alluded to. Murphy set out on his journey and found much greater difficulty in bringing together the bands he wanted than he anticipated. Here he met Black Kettle, who informed him that if he would go to Medicine Lodge Creek, he, Black Kettle, would assist him in assembling the Indians. Murphy expressed some doubts as to whether it would not be extremely hazardous to venture into that country. He could not take with him a military escort, as that would alarm the Indians and prevent them from assembling. Black Kettle, a Cheyenne chief, Little Raven, an Arapahoe chief, and Satanta, another chief, promised to accompany him to protect and aid him in his undertaking. Murphy went to Medicine Lodge Creek, escorted by these chiefs and forty warriors belonging to Little Raven’s band. These chiefs also rendered very valuable service by sending out runners to the hostile Indians and bringing them into the council.

This was the attitude of the chiefs in August 1867, only a few months after the burning of their village by General Hancock. The council was held and a treaty entered into, about 7,000 Indians being present, the large attendance being mainly due to the exertions of Black Kettle and the other chiefs. Moreover, Black Kettle expressed the greatest pleasure when he beheld the signing of the treaty. During the conference held here the Peace Commissioners promised that food and agricultural implements should be furnished to the Indians and that provision should be made for their education. Those promises were carried out until the appropriation became exhausted, and Congress having failed to make any further appropriation the issue ceased. The Indians, therefore, depending upon these promises to a great extent, neglected to provide their usual supply of food and became very destitute. They suffered terribly, and thus it happened that [wagon] trains passing through their country were importuned for food, and when it was refused they took it by force.

Matters were in this deplorable condition when General Sherman notified the Secretary of the Interior that he had sent General Hazen and Colonels Boone and Wynkoop to Fort Cobb with about $50,000. General Hazen was instructed to collect all the friendly Indians from those tribes then engaged in hostilities at or near Fort Cobb and to furnish them with provisions, and thus endeavor to induce them to go upon reservations. Orders were also given to issue the annuity goods to such friendly Indians as should comply with the call. From all the evidence that can be obtained in regard to the object which these Indians had in view in moving towards Fort Cobb it is fully believed that they were a party of about 300 friendly Indians whom Black Kettle and other chiefs had prevailed upon to respond to the call of General Hazen and by the direction of Colonel Wynkoop, their agent; that they were then on their way to Fort Cobb, and had reached a point within about fifty miles of it. Confiding in the promises of the authorities, the Indians retired to rest without surrounding their camp with a guard, a precaution which is never, under any circumstances, neglected when moving as a war party.

In the dead of night their camp was surrounded by Custer’s troops, and the friendly Indians were slaughtered to the tune of “Garry Owen.” It is understood now that several Cherokee Indians who had borne arms in the Union armies during the late rebellion were with the party under Black Kettle. They had accompanied the party on a trading expedition, and were killed with the warriors and braves of the Cheyennes and Arapahoes. This matter, it is said, will be laid before the Committee on Indian Affairs and a committee of investigation asked for, in order that the blame may rest where it properly belongs.

What shall be said of the blunder, not to call it by a harsher name, which sacrificed young Hamilton (grandson of Alexander Hamilton and a recent graduate of West Point) and the other brave but inexperienced youth, who in obedience to the orders of their superior officers, met their death in such a cause. Heavy is the responsibility resting somewhere. Justice and humanity call for a thorough and searching investigation and exposure of all the facts in the case. It will be a sad state of things for our nation, should the desire for military aggrandizement, with a view to political advancement without regard to the means or motives to effect it, ever become the ruling principle among us. We profess to be a Christian people. As such we are bound to deal fairly with our fellow creatures, whether civilized or savage. There is reason to apprehend that the battle of the Washita will add nothing to our credit as a civilized and Christian nation.